|

|

| photo: Urvi Nagrani | |

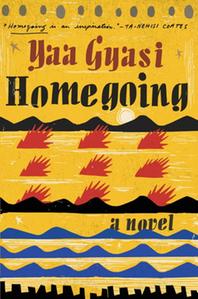

Yaa Gyasi was born in Ghana and raised in Huntsville, Ala. She holds a BA in English from Stanford University and an MFA from the Iowa Writers' Workshop, where she held a Dean's Graduate Research Fellowship. She lives in Berkeley, Calif. Her first novel, Homegoing (Knopf, June 7, 2016), alternates between the parallel lineages of Ghanaian half-sisters separated by the African slave trade. See our review below.

Homegoing is a 250-year epic distilled to the size of a contemporary novel. How did you choose which characters to focus on to tell such an expansive story?

As I was writing, I didn't work off an outline, but I did work with a family tree that I pasted to the wall above my desk. It had the two branches of the family on either side of the paper, and then the names of the characters, their genders--if I knew them--the years that I thought the bulk of their story would take place, and then just one thing that was going on politically or historically in the background of that time period. I wrote chronologically with the hope that as I was writing one character I would get some ideas for what would happen to their descendants. I didn't plan it out; I hoped to be led by the stories as they were happening.

With such a broad scope to cover, you still plumb the depths of each character. How did you balance historical research and novelistic flourishes as you wrote?

I had received a research grant from Stanford University, where I did my bachelor's, to travel to Ghana and research a novel. I had a different idea in mind for the novel, but then I got there and it didn't really pan out. I was bummed about it, and a friend came to visit. We decided to go see the Cape Coast Castle, which I hadn't visited before and didn't know much about. We took a tour of the castle, and the guide started talking about how the British soldiers married the local women, which was something that I'd never heard before. He showed us the upstairs level, with the cannons facing out to sea and the church and all this splendor of that time period. And then he took us downstairs to see the dungeons. Just being there, it felt haunted. I knew that I wanted to write about it, but I didn't know how to approach it. I wrote in my journal that night that I was scared of how much research this book was going to take.

But I started with a book called The Door of No Return by William St. Clair; it's a book that looks at archival data about the Cape Coast Castle and its goings on during this time period. That was my entry point for the first few chapters of Homegoing, and after that I would find a book or two along the way that would give me some sense of what was happening historically during the time periods that I wanted to write about. Once I got enough to spark my imagination, I would set the book aside. I wanted the research to feel exploratory, to open up possibilities, and not make me feel closed off--like I can only write if I know what color shoes they would be wearing in 1870. One of my favorite characters is Quey, a biracial Fante villager who falls in love with his friend Cudjo, but avoids him after Quey's return from years living in London. Later, Quey's son James exiles himself to Asanteland. In what ways do you think exile shapes individual identity compared to remaining within a close community?

One of my favorite characters is Quey, a biracial Fante villager who falls in love with his friend Cudjo, but avoids him after Quey's return from years living in London. Later, Quey's son James exiles himself to Asanteland. In what ways do you think exile shapes individual identity compared to remaining within a close community?

Quey's exile is not self-imposed; he gets sent to England ostensibly for school but also, as we learn, because his father is frightened of Quey's sexuality. It shapes him because England in that time period obviously was very different from what he knew, but he also gets to see the slave trade from the British perspective, and he comes back with a choice: Does he work for the family business, or does he do his own thing?

His son James makes the choice not to work for the family business, and self-imposes this exile. In James's chapter, his love interest talks about how she wants to be her own nation, and I think that's a big part of this novel. These exiles are about how you forge your own identity, forge your selfhood in the midst of these very large socioeconomic, political structures that are imposing themselves onto your life and onto your choices. How do you create your own identity? How do you say no to something that is so much larger than you? James tries to find a way, and whether or not he's successful is up to the reader to decide.

Each of these chapters has these gray moments as people try to figure out whether to go along with what's happening, or if they should make their own way.

Your characters display a broad spectrum of virtue and vice. Was it difficult for you to stay removed and let your characters be themselves amid something as inhumane as the slave trade?

It was difficult, but also it felt like part of the point, to show people in all of their humanness. Those of us in the present have a tendency to look upon the past, look upon our ancestors as though they were somehow less intelligent, less moral than we are, and that's why things like slavery or the Holocaust or whatever huge tragedy of whichever time period happened. But in fact, they were people just like us, with hopes like our hopes, and dreams like our dreams, and flaws like our flaws. I think it's harder to accept the fact that, if we were living in 18th-century Ghana, perhaps we would be doing the same things that these people did. It's harder to go against the grain if the grain is this large, bigger-than-you force of evil. It was really important for me to show that these characters are individuals just like us, that they are doing what they think is right, as awful as it sometimes may be.

The other half of the novel focuses on the side of the family sold into slavery in the United States. How did you approach writing the American history/landscape and writing those of Ghana?

I tried to read widely. I didn't read much fiction while I was writing, but before I started I was reading Achebe and Adichie, and also reading Morrison and Edward P. Jones, trying to get a sense of the different voices that are possible for West African fiction and for African American fiction. One way that I was thinking about this novel was as fables and folktales, these passed-down stories, not exactly realism, but just off of it so it feels believable yet still invites magic into it. Conceptualizing it that way, with the Ghanaian stories kind of as fables and the American stories kind of as folktales, helped me in terms of figuring out how to make the voices differ while keeping the main narrative voice consistent and cohesive. That was one of the biggest challenges of this novel, giving some texture to each of the chapters when we switch countries.

I loved your book, as well as Taiye Selasi's Ghana Must Go; would you mind recommending some more Ghanaian writers and books?

Oh yes! I would definitely recommend Mamle Kabu's writing, as well as Ama Ata Aidoo's. Along with Taiye Selasi, they are three to certainly look into. --Dave Wheeler, associate editor, Shelf Awareness