|

|

| photo: Walter Kurtz | |

Bill Hayes is the author of The Anatomist, Five Quarts and Sleep Demons. He is a recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in nonfiction and was a visiting scholar at the American Academy in Rome. He is a frequent contributor to the New York Times, and his writing has appeared in the New York Review of Books and Salon, among other publications. His photographs have been featured in Vanity Fair, the New York Times and the New Yorker. Insomniac City (Bloomsbury USA, February 14, 2017) is his memoir of life in New York City with Oliver Sacks. (See our review below.)

Insomniac City takes an evocative, mixed media form: essays, journal fragments, photographs. I love the line you mention scrawling on an envelope, "New York will always answer you." Did you imagine that the city would become its own character?

I always knew that New York would be the main character of this book, because it saved my life in a certain way after losing my partner Steve. It welcomed me with open arms, with its beauty and craziness and chaos. My goal was to capture my experience of New York: a combination of life on the street or subway, where I encountered New Yorkers--but also my parallel life with Oliver in our apartment in the West Village. When the photographs appear in the book, I wanted them to appear almost as passing strangers. They don't come with stories explaining them. It's like passing an interesting face on the street--there are three lovely women at the bodega and when you turn the page, you're on to another story.

What does the camera offer you as an expressive outlet that you hadn't realized before?

What does the camera offer you as an expressive outlet that you hadn't realized before?

I first bought a camera after Steve died. I made a spontaneous trip to London. This was right before people commonly used cell phones as cameras, so I bought this digital Canon, one that I could slip into a pocket. That trip was a significant one; it was my first time abroad alone, newly single again, and the camera kept me company. It gave me a reason to leave the apartment and discover new parts of London and interact with people. I was drawn to taking pictures of people, but it wasn't until I moved to New York a year later that I really began to use the camera. I slipped it into my pocket and hopped on the subway to Washington Heights or Harlem or the East Village. It became a way for me to get to know the city and get to know New Yorkers. Once the limitations of that camera became clear, I bought a slightly better camera, and then a slightly better one. Then, when Oliver and I were together, it became part of our relationship; I would be out on the street, taking pictures, meeting people, and then come back at the end of the day with stories to share and pictures to show him. So it's evolved over time to the point where I take photography as seriously as my writing.

You demonstrate such openness to the world around you. Had you always felt that way, or was that something that developed with the camera?

In a certain way, yes, that openness is part of my DNA. Which I suppose has its flip side: gullibility. But I've also seen that openness can bring out the same in strangers. I always ask permission from the person I'm photographing, so that immediately involves an encounter with a stranger. At least half the time people say no, but if they say yes, it's usually a very quick encounter. I only take two or three pictures. And I think there's something very beautiful about that, an anonymous encounter that can be very intense in a certain way, and the trust placed in me, and the openness they give me when I take their photograph.

|

|

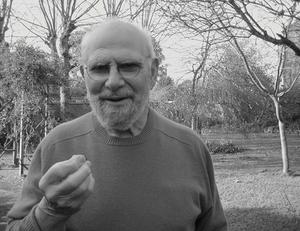

| Oliver Sacks (photo: Bill Hayes) | |

Your relationship with Oliver came late in your life and much later in his--for you after Steve's death and for Oliver after considerable solitude. How was it to open up to each other at that time in your lives?

As you noted, I had just come out of a long relationship that had ended tragically; I wasn't looking for a new relationship. I had also been out as a gay man and written a lot about being gay. Oliver had led an almost monk-like solitary existence, devoted to his patients, his practice and his writing. So to put us together, there were definitely challenges in making the relationship work. But at the same time there was something charmed about it. He was so ready to open his heart up completely and fall in love.

One of the most challenging things in the very beginning was the fact that he was still very private about being gay. Even people within our own apartment building didn't understand the full nature of our relationship. It definitely had something to do with the vast difference in our ages--almost 30 years. Often people assumed that I worked for him. Or people assumed that we were related, and so they would ask me about my "father" and him about his "son," which we both found charming and funny because he had a pretty strong British accent, and I don't--I'm from Washington State.

|

|

| A Small Parade (photo: Bill Hayes) | |

Even though Insomniac City begins and ends with death, you manage to infuse the stories of both with such joy. Did you find that writing about it was more cathartic or more painful?

I don't know if catharsis is the first word I would use to describe the process, but it felt good to create something beautiful out of those two very painful losses in my life. And I end the book on what feels like a love letter to New York City itself. I write about taking a short walk after Oliver died to visit Ali in the smoke shop down the street, sharing the news with him, and how he made me laugh and how good that felt. Ali is a recurring character in the book, which was not something I planned from the outset, but he's part of my life. We live in the same neighborhood, and more than ever I do believe in the importance of neighbors and neighborliness, especially since the 2016 election, so I'm happy the book ends with that scene with Ali.

|

|

| West Village (photo: Bill Hayes) | |

There's a lot of fear today of strangers and the other, and I think, without being particularly political, you challenge readers to talk to our neighbors and the strangers on the street.

I learned that after Steve's death, because it was so shattering. The neighbors in my apartment building helped me so much--in big and small ways. It's different with Oliver's death--the neighborhood is global. People from all over who loved him have reached out. One little passage that I almost cut out because of length, but I'm so glad I left in, was the short chapter about the homeless man named Raheem, whom I first spotted on the street with his several shopping carts full of plastic bottles and cans that he collects and trades in for money. I had seen him on the streets before, and asked to take a photograph, and then we had such a good conversation. I've seen him many times since, and we always say hello. I have so much respect for him because he has given his life a sense of purpose by going through the garbage we all leave behind--and there's garbage all over New York City--and picking out the plastic bottles and cans, organizing them and trading them in for money. I admire Raheem because he does not have an easy life by any means, whether he's sleeping outside or being chased away by cops or being insulted by neighbors in high-rise buildings who don't like his shopping carts in front of their building. But he's got real dignity. He's a survivor. --Dave Wheeler, associate editor, Shelf Awareness