Chris_Malpass.jpg)

|

|

| photo: Chris Malpass | |

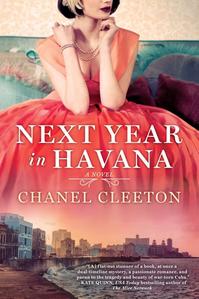

In Florida, Chanel Cleeton grew up on stories of her family's exodus from Cuba following the events of the Cuban Revolution. She is the author of 11 books, including Next Year in Havana (Berkley, $15), her first historical novel. Our review is below.

Your family's history was part of your inspiration for the book.

My father and my grandparents left Cuba in 1957, a little bit later than the family in the book. My grandparents always thought they would be able to return one day. From the time I was a young child, they would paint the picture of their life there for me. They lived with us, and we ate Cuban food all the time. They had that huge nostalgia for their homeland and they were never able to go back.

Some of my relatives had planned to return to Cuba for a family reunion when travel from the U.S. became possible. But my grandfather felt strongly about not supporting the regime by returning, and that opened up a series of family discussions. My dad told me a story about how, before they left, everyone came over to my grandparents' house in the middle of the night and buried their valuables in a box in the backyard. As a writer, that really inspired me: If you had a similar box, what would you save? They also buried items in the walls of their home, to try to preserve whatever they could.

I haven't been to Cuba, but I talked to friends and family members, people who lived there once or had been back recently. We also have photos and documents that were smuggled out, and my grandfather's hand-draws maps of Havana. It's one of his passion projects. So I was able to re-create some of the buildings, the neighborhoods, the city as it was then.

How did you decide to tell the novel's story through a dual-narrative structure, involving women from multiple generations of the same family?

I wanted to explore how the Cuban revolution is ongoing for so many exiles. In talking to friends who aren't as familiar with it, I was surprised to hear that people didn't understand why Cubans cling to their homeland so much. I wanted to explore what that meant for the exiled community--what it meant for my grandparents' generation and my father's generation, who left their home with nothing.

For my generation, we struggle with identity a little bit, because we don't have the same tangible connection. My mother is American and my father is Cuban, but I've never even been to the country. We have this unresolved sense of our place in the world, as Cubans and Cuban-Americans.

Many Cubans who immigrated to the U.S. right after Castro's rise to power expected to return soon, but ended up building lives in Florida and elsewhere.

I think when the revolution happened, people expected to return in a few months. That's still a toast we make at New Year's Eve: Next year in Havana, which became the title of my book. There have been so many moments where Cubans thought, "Okay, we'll go home soon." That makes it hard when you are building a life.

My grandparents were closer to their 50s when they came to the U.S.: later in their careers and their lives. How do you put down roots when you're always looking to another country? We were always waiting for Castro to die. There was definitely an expectation in the 1990s that Castro would pass away and everything would go back to the way it was. As I was writing the book, the U.S. was opening relations with Cuba, and we thought we might see a sea change there, but that has been dialed back. Castro died right as I was finishing up the manuscript, but things will never go back to the way they were before he came to power. Can you talk about the Cuban community in the U.S.?

Can you talk about the Cuban community in the U.S.?

I tried to focus on the idea of Cubans helping Cubans, and the sense of community and sacrifice. That really impressed me about my grandparents' stories: they had a huge network of friends and family that they kept in touch with. It was a story of friends coming together and making sacrifices for each other. When my grandparents came to this country, they came as refugees, and family friends helped my grandfather get a job and helped my grandparents find an apartment. That's one thing that comes through: how much people have built their own community outside of Cuba. They've passed down the stories: most people didn't get to bring much with them in terms of possessions or documents, but that oral tradition and culture are still very strong.

Both of your protagonists fall in love with men who have radical ideas about how to reshape Cuba. Tell us about the differences and similarities between the two men.

I knew that, no matter how hard I tried, I was always going to be writing as the granddaughter of an exile. That's the genesis of this story, and my perspective. But I wanted to give a holistic portrayal, as best I could. With Pablo [Elisa's love interest], I wanted to show a good man who was trying to do the right thing, who was passionate about his country. A young girl like Elisa, from an affluent family, was not going to have access to that segment of society: he was a great foil to her. And she didn't have to agree with him about everything. As for Luis [Marisol's modern-day love interest]: there's a new generation of Cubans who are trying to use technology to demand change within the government and the country. I feel like the two male characters told the side of the story that I couldn't tell.

In my research, I listened to a lot of recordings of men who were involved in the 26th of July movement. I kept hearing what their goals were when they got involved, and how those goals didn't come to fruition. They were kids playing at revolution, and they didn't know how to build a government. They didn't really have a plan in place. All they knew was that they wanted to get rid of Batista. They didn't know anything about governance. I wanted to flesh out that idea of good intentions, being dedicated to your country and your beliefs, but maybe it didn't work out the way you wanted.

The novel explores the tensions, overt and subtle, between Cubans who fled to the U.S. and those who stayed. How do you see that?

In Cuba, there's a lot of diversity. There are diverse experiences both among the exiles and those who have stayed. Socioeconomically, for example, there were people who were doing well under Batista's regime. It was more of a European class: the big plantation owners, whose industries were threatened almost immediately. For that exile community, Fidel has done no good in Cuba. But for a lot of the people who stayed, there have been some improvements: healthcare access, the national literacy rate. Racism is obviously prevalent, both under Batista and Castro. The official position is that we've eradicated racism, but that's not true. For a lot of people, it's a question of: What did you lose? --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams