_Catherine_Marin.jpg)

|

|

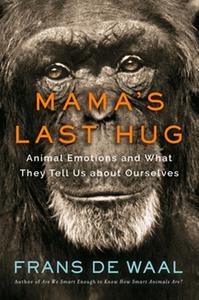

| photo: Catherine Marin | |

Frans de Waal has been named one of Time magazine's 100 Most Influential People. The author of Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are?, among many other works, he is the C.H. Candler Professor in Emory University's Psychology Department and director of the Living Links Center at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center. His new book, Mama's Last Hug (W.W. Norton, $27.95; reviewed below), explores the emotional life of animals. Originally from the Netherlands, de Waal now lives in Atlanta, Ga.

Despite the title character (chimpanzee matriarch Mama), Mama's Last Hug doesn't deal strictly with primates. What expanded your interest to include all mammals?

I have a long-time (childhood) interest in animals, all animals, and started my studies with birds and rats, and only later moved to monkeys and apes. I was trained as an ethologist in the Netherlands, and there studied the world's largest zoo colony of chimpanzees, which gave me many ideas for later work. It started with work on aggressive behavior and politics (I wrote Chimpanzee Politics at the time), but soon thereafter moved to peacemaking, cooperation, empathy and the like.

Speaking of empathy, in the "Body to Body" chapter you note how females--across species--are more nurturing and empathetic than males.

In general, females in all mammals have stronger caring tendencies, and that includes stronger empathy for others. This is true in humans, but also in all of the primates I know. The origin of these caring tendencies is no doubt maternal care, which is obligatorily female and only optional for males. This doesn't mean that males lack empathy. There are species, ours included, in which males care for offspring, care for each other, care for their family. In these species the capacity for empathy expanded and reached other areas of society, including males. I always think in potentials rather than the dominant behavior. The potential for empathy is well-developed in males, and since we are a powerfully cultural species, we can build on this.

One of the recurring themes in your writing seems to be that humans have historically discounted so much when it comes to animals, but you explain how that is changing. What area (or areas) could still use a lot of work on our part?

One of the recurring themes in your writing seems to be that humans have historically discounted so much when it comes to animals, but you explain how that is changing. What area (or areas) could still use a lot of work on our part?

Within the university we still have entire fields (anthropology, philosophy, humanities, economics) that tend to ignore the biological nature of our species. They will admit that we evolved from other primates but are not ready to say that we think and feel like other animals. Humans are considered extremely special. For example, consciousness was and often is thought of as a uniquely human characteristic. This is where change has to start. It's a different way of positioning the human species--not as separate from nature but as part of it; not as a half-god, but as an animal.

Part of the problem in the world today with the ecosystem (global warming, loss of species diversity) stems from this illusion of our species that we are separate from nature and can do whatever we like with the Earth. It is intellectually a false proposition that is now backfiring. The planet is "protesting."

Does anything still surprise you about the animals in your work?

We still keep being surprised. For example, you may have heard about the recent study in which fish recognize themselves in a mirror. Who would have thought? I have questions about the study, and am not totally convinced, but still we keep expanding our horizon, and keep discovering that all animals, not just the primates, have a complex cognition. My book is more about the emotions, of course, but also here, many new discoveries have been made or are about to be made, offering us a much more complex picture of animal life than we used to have. We are in the middle of a revolution of our understanding.

I think neuroscience will offer new discoveries soon, as scientists who work in this area, mostly on rodents, move away from simplistic animal behavior and learn more about social behavior and mental capacities. Once they start testing those out, we can expect many new discoveries.

What's next for you in your scientific work and/or writing?

I am looking forward to doing less research and more writing and traveling. I am thinking about my next writing project, but it is still top secret. I usually try to stay close to the subject matter I know best, which is the behavior of primates and other animals, hence no doubt that will be central to whatever I do next. --Jen Forbus