|

|

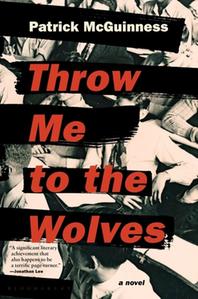

| photo: Mari McGuinness | |

Patrick McGuinness, who was born in Tunisia in 1968, is a professor of French and comparative literature at Oxford University and a fellow of St. Anne's College. He has previously published books of poetry, works of nonfiction and the novel The Last Hundred Days, which was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize. His novel Throw Me to the Wolves (reviewed below) has just been released by Bloomsbury Publishing.

Throw Me to the Wolves has the signposts of a thriller--a crime to solve, a detective narrator--but it somewhat subverts the genre by lingering on the main character's personal relationships and on his musings unrelated to the crime. Did you set out to break the traditional rules of thriller writing, or did you just let the story take you where it wanted to go?

I was guided by the story and by the holes in the story, which perhaps interested me more. Thrillers are pushed by a desire to explain, by the belief that explaining things helps you understand them. I'm not sure it works like that. I wanted to write a book that toyed with the genre, but which showed, basically, that real life is both more complex and less complex than a thriller. I often try to interrupt the pacing so it doesn't become too much like a linear narrative, and to interrupt time zones, too. I wanted intermissions for musing, or remembering, or for cultural commentary. The whole book takes place over three days and at the same time it takes place over three decades.

In the novel, you name-check Dorothy L. Sayers and Agatha Christie's Poirot and Marple, not to mention Rumpole and Columbo; you know your way around the mystery and thriller world. Who are your favorite authors and characters in the genre?

I love police procedurals, yes, in film and in television. I loved Columbo because it inverted the genre: the mystery lay not in the who, the how and the why (we knew whodunit and how and why at the start) but in how it was resolved. It became a psychological game, usually based on the murderer's hubris.

A critique of tabloid journalism is a major theme in Throw Me to the Wolves. Was there a particular tabloid-inflamed event that inspired you to take on the subject?

Yes, the case of Christopher Jefferies, a teacher arrested by the police and hounded by the press for the murder of Joanna Yeates in 2010. He was my teacher, and we liked and admired him, and he was, for me, the teacher who taught me to love books and ideas and, eventually, I guess, writing. Though the novel is not about him, and the character in my book is visibly as well as anecdotally not him, I used my book to express some of the outrage and anger I felt at what was done to him. I was especially disgusted when some of my contemporaries at school were prepared to lie about him in the press, either for money or attention, and make up stories about his behavior towards us. He was, of course, exonerated. As in so many cases in real life, the murderer was a toxic male heterosexual, with a girlfriend and a good job, a penchant for sexual violence, lying and pornography. Not the strange, sexually ambiguous, fastidious single man who reads literature and likes opera, behaves a little distantly and carries a hessian bag with "I Love Books" written on it... I'm sorry--just writing this out makes me angry, so let's move on....

Here in the United States, there's nothing quite comparable with the English boarding school in terms of strictness and formality. Did you attend a school like Chapelton?

Here in the United States, there's nothing quite comparable with the English boarding school in terms of strictness and formality. Did you attend a school like Chapelton?

I did, but it wasn't as bad. I took what I knew, and, as perhaps we all do in fiction, I pushed it along the truth-fiction spectrum until I reached the point I needed for a novel plot--thankfully, because some of the stuff in the story is pretty traumatic. These schools are an English phenomenon, and they produce the British ruling class: essentially a stratum of venal and entitled sociopaths, sent to these places by their parents, who went to the same school, and so on for decades and in some cases centuries. They are places of teacher-endorsed bullying and emotional and physical violence; snobbery is rife, as is racism and classism and sexism. Or they were then. These schools underpin the English class system and help it self-perpetuate. The fact that they cost tens of thousands of pounds a year, and yet manage to call themselves charities and avoid proper taxes, is the final irony. The products of those schools happen to be in charge of my country, which explains quite a lot about the state we're in.

Prof and Gary are such a fantastic detective team--an odd couple that doesn't sound the same notes as odd-couple combos we've seen in the past. Could you see revisiting this team in another book?

Maybe, yes. It occurred to me that they needed another outing--Lord knows there's enough bad stuff for them to be getting on with. But in this book, the narrator is also solving the mystery of himself, so the next story, if there is one, needs to be as urgent and as traumatic. Perhaps Gary can have a trauma? Gary's unique feature is his normality in a world of damaged people. At one point, he suggests, ironically, that in a world of misery memoirs and trauma narratives, not having a childhood trauma is in fact the new childhood trauma. Maybe I could start there and take him up on it? --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer