|

|

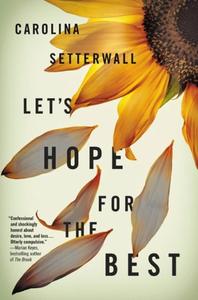

| photo: Sarah Mac Key | |

Carolina Setterwall was born in 1978 in Sala, Sweden. She has worked in music and publishing as an editor and writer. Setterwall lives in Stockholm with her son, and makes her literary debut with Let's Hope for the Best (Little, Brown, $27; reviewed below), autofiction written in response to the death of her partner, Aksel, when their son was just eight months old.

Why did you choose the format of autofiction, rather than a more traditional memoir, to tell your story?

Actually, it wasn't really a conscious choice, at least not in the beginning. To be honest, I didn't exactly know what made a story autofictional (rather than biographical) when I started writing this book. It was more a case of me writing the way I wanted to write, and the story I would have liked to have read myself, than having a plan for exactly what genre the story would fit into. So I'll try to answer this question from a different angle.

When I set out to write this book, I knew I wanted to tell a story about a grieving process, a loss and also a modern love relationship that I could not only relate to, but that also exposed (side by side with the "purer" aspects) the parts of a grief/loss/relationship, that weren't... so polished. I wanted this story to be the opposite of Instagram, if you know what I mean?

I wanted to share the days, and thoughts, and feelings that are entangled in both the grief and the love that I had felt shame about. They're normal, but we tend not to talk about them. And with the shame comes the hiding, and with the hiding comes the feeling of isolation, and with the isolation... well, the grief just intensifies.

In regards to the autofiction, while it is true that I lost my partner under the same circumstances as are told in the book, Let's Hope for the Best still is a fictionalized story, constructed as a novel rather than a biography. Most of the events that take place in the story took place in my real life, too, but not necessarily in the exact same way or in the exact same order.

Let's Hope for the Best's staggered storylines make it fascinating--chapters alternate from the early days of your romance to your reactions after the tragedy. Was it hard to decide how to break the story up, or did this feel natural?

Let's Hope for the Best's staggered storylines make it fascinating--chapters alternate from the early days of your romance to your reactions after the tragedy. Was it hard to decide how to break the story up, or did this feel natural?

Actually, this (too!) was also more a matter of coincidence than a strategy, or plan. At first I tried to tell the story without involving the person who was lost, but soon found out that I couldn't tell the story without involving what was lost: a past, a shared future, a relationship, a person, a love. To mix two timelines, one after and one before the event that changed everything, was a way to capture how death changes things irreversibly for the people being left behind.

You spend a lot of time analyzing the effect of Aksel's death on your young son, Ivan. One of the more poignant scenes occurs at Ivan's preschool when the class of two- and three-year-olds are talking about how things die. Do you find that it is generally easier for children to process grief?

Both yes and no. It's easier because death hasn't yet become taboo for young children. And they're not particularly good at metaphors. So, when talking about death with kids, you have to approach the subject in a really matter-of-fact kind of way. In my experience, they don't judge, and their never-ending curiosity makes it, in a way, easy to talk about. And difficult to avoid talking about!

On the other hand, it's really hard for kids to understand the infinity of death. My son had a long period of time when he was sure dad was coming back one day. It's absolutely excruciating having to explain that he's gone forever. That he's still around in terms of our memories, and that he would always be his biological father, but in a physical sense, he's still gone and he would remain gone.

Can you give us a glimpse into your writing process for Let's Hope for the Best? Did you squeeze writing in around your day job, or did you take a break from work?

When I wrote Let's Hope for the Best, I worked part time for six months and had two days every week completely dedicated to writing. I also wrote during the evenings, when my son was asleep. Some weeks I tended to hate myself for not having written "enough" (in terms of both quantity and quality) during the days that I had spent doing other things than writing (for example: laundry, taking care of an ill child, staring into the wall, scrolling through social media networks). Luckily, some weeks the words just flew.

I remember the days of writing this book with mixed emotions. It wasn't necessarily the writing that was hard--it was navigating through life at that time. I think, in many ways, writing this story gave me a purpose with my days--a purpose in addition to raising and taking care of my son.

--Jessica Howard, bookseller at Bookmans, Tucson, Ariz.