|

|

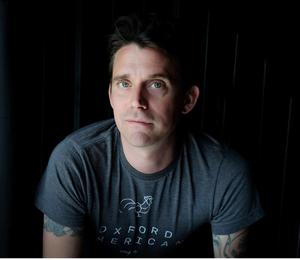

| photo: Saja Mantague | |

M. Randal O'Wain holds an MFA from Iowa's Nonfiction Writing Program. Originally from Memphis, Tenn., he now lives in southern West Virginia. His essays and short stories have appeared in the Oxford American, Guernica, Pinch, Booth, Hotel Amerika and storySouth, among others. He is the author of the memoir Meander Belt: Family, Loss, and Coming of Age in the Working-Class South, a collection of essays that reflect on how a working-class boy from Memphis came to fall in love with language, reading, writing and the larger world outside of the American South. Meander Belt ($19.95) was recently released as part of the American Lives Series from the University of Nebraska.

In your preface, you write about privileging verisimilitude over accuracy. What does that mean?

Accuracy is fact, right? It's information, it's irrefutable. But we already know that memory is inaccurate. So to ask how could you ever know what is real, what is not real, how you can depend on your own memories... to me, that's a boring conversation. We're trying to get to the heart and guts of the experience, the human condition, and not a verbatim account of truth.

I heard Kevin Brockmeier read from his memoir A Few Seconds of Radiant Filmstrip, about being in the seventh grade. Inevitably, when you write a memoir that uses the techniques of fiction rather than digressive or expository techniques, people will ask this question: "Well, what about dialogue? Is your memory that good?" And his answer was amazing. He said, "You know, pretty often I get asked that question, but nobody ever asks me how I remember the sun motes falling through my living room as I'm laying on my back staring out the window. Nobody ever asks me about those specific concrete details that are just as 'inaccurate' as dialogue." Because we just sort of buy those as being an acceptable form of essential truth. And he said, "I remember some dialogue, and I remember some details, but really what I'm trying to get at is what it was like to be a seventh grader, afraid to go outside or afraid to get up off that floor."

The story presents itself as it is. Either as inhabited space, one that might require techniques of fiction, or as a cerebral space, one that you turn over as a three-dimensional object, that you work with in your mind. Then the exciting part for the reader is watching the writer turn it over. Or if it's an inhabited space, the exciting part for the reader is watching it go by, as if it were cinema. Those are very different feelings. Meander Belt I felt the whole time in my guts. If I were to write it in a way that might come off as more essayistic and therefore more true, I suppose, it would seem so wrong. Because it wasn't a cerebral book. It's a bodily book.

How did this collection come to be?

I read Jo Ann Beard's The Boys of My Youth, Ryan Van Meter's If You Knew Then What I Know Now and Harrison Fletcher Candelaria's Descanso for My Father (also an American Lives book)--those three collections were so impressive. I just loved them. That was how I wanted to write this story. But I was convinced by an agent to turn it into a memoir. I tried for a few years, and failed terribly. When I turned in the final version of the memoir, she dropped me. She said that it wasn't a book that she wanted to read. And that was hard. That was devastating. But it was also freeing.

I'd been publishing these essays throughout the time of working on that memoir, just to kind of stay in the game, keep my foot in the door, test things out. "Arrow of Light," "Rain over Memphis," "Thirteenth Street and Failing" were early, standalone essays. And then there were others I started pulling out and changing. When the agent dropped me, I was like, oh, I'm free! And I went back to the original intent, and it flowed very easily.

I'd been publishing these essays throughout the time of working on that memoir, just to kind of stay in the game, keep my foot in the door, test things out. "Arrow of Light," "Rain over Memphis," "Thirteenth Street and Failing" were early, standalone essays. And then there were others I started pulling out and changing. When the agent dropped me, I was like, oh, I'm free! And I went back to the original intent, and it flowed very easily.

What I've learned, what I have to say over and over again to myself, is to trust myself. I gave too much of my trust to a business relationship. Someone who didn't know my work as well I did, or my intent. Obviously we need the gatekeepers and go-betweens, like agents, but maybe we put too much trust in them. It's just a business relationship. Not an artistic relationship.

These essays draw on intimate and often painful details. How do you care for yourself through that process?

Those details are painful at first, and then you get them on the page, and they become something else. They become something that's beyond you. The saddest thing for me was that they didn't hurt anymore. That the book doesn't hurt. I miss it hurting. I extracted, mined very personal details that then were not a part of me anymore.

I don't know if there's ever a way to fully take care of yourself. It's a strange thing to turn memory into art.

What did you learn in writing this book?

That I never want to write about myself again. It was so difficult. There are so many constraints, going back to your initial question about truth. I wanted to tell the truth. And that meant having to talk to family members, to talk to them again and again, to make my poor mom go over it again and again.

There are people out there who keep writing memoir! Memoir after memoir after memoir! What's wrong with you? Haven't you ever heard of the autobiographical novel? Make shit up! The mining of memory, that whole process is very challenging. At times it can feel like you're just this egomaniac, and there are so many other things that a writer can look at besides themselves.

Even though I use a lot of techniques from fiction, I learned a lot about telling the truth. What it means to be vulnerable. So many times I tried to make an excuse for my behavior or apologize for my behavior, but I learned just to let it stand. To be okay with letting it stand. This was helpful for me as a writer and as a person. We're better off if we can be honest with ourselves about how fucked up we are as well as how good we are. --Julia Kastner, librarian and blogger at pagesofjulia