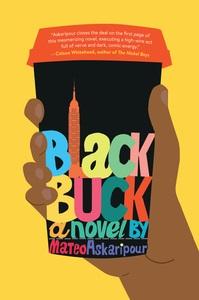

Mateo Askaripour was a 2018 Rhode Island Writers Colony writer-in-residence, and his work has appeared in Entrepreneur, Lit Hub, Catapult, The Rumpus, Medium and elsewhere. When he's not writing or reading, he's bingeing music videos and movie trailers, drinking yerba mate or dancing in his Brooklyn, N.Y., apartment. His debut novel, Black Buck (Houghton Mifflin, January 4; reviewed below), is a hilarious, razor-sharp skewering of America's workforce.

Mateo Askaripour was a 2018 Rhode Island Writers Colony writer-in-residence, and his work has appeared in Entrepreneur, Lit Hub, Catapult, The Rumpus, Medium and elsewhere. When he's not writing or reading, he's bingeing music videos and movie trailers, drinking yerba mate or dancing in his Brooklyn, N.Y., apartment. His debut novel, Black Buck (Houghton Mifflin, January 4; reviewed below), is a hilarious, razor-sharp skewering of America's workforce.

What inspired you to take on corporate sales?

This question reminds me of what one of my brothers once told me: "In karate, in order to break a wooden board, you need to aim at what's behind it." The same applies to Black Buck. It wasn't my intention to take on corporate or startup sales; I planned to call into question America itself. Sales and startups were just the most readily available access points, given my experience with them. Plus, they're rich with astronomically high highs and the lowest of lows, and I hoped that any story centered on them would be engaging, entertaining and, if done right, earnest.

Darren, the main character, makes choices that are simultaneously difficult and easy to understand. How challenging (or not) was it to write a character like him?

I'm still in a place where I read reviews, and most people, including those who enjoy the book, seem to dislike Darren for the majority of the book, which I understand. Some have called him an "anti-hero," which calls into question the definition of a hero itself. Many people looked at John Wayne and Hitler as heroes, you see what I'm saying? With Darren, I sought to create someone who felt extremely real, relatable, and worth rooting for. And when his potential is activated by Rhett, his journey, no matter how hard it can be to watch, had to match the intensity that I wanted people to feel while reading. It was also important to me for Darren's path to redemption to be pushed on him rather than be a conscious choice of his own. Writing him wasn't too difficult, but it was hard for me to subject him to so much pain, and then have him turn around and hurt others.

Advice from the elders in Darren's life influences some of the significant decisions he makes. Can you speak to this?

I've never been asked this before, so thank you for the question. It's true, he largely looks to his mom, Mr. Rawlings, and Wally Cat for advice. His mom helps him dress for his first day at Sumwun. Mr. Rawlings tells him to not let the white boys at work beat him down. And Wally Cat gives him so much game it's hard to understand why Darren would ever stray away from it. Darren's shift to Sumwun, and receiving social, spiritual and emotional advice from someone like Rhett, hits the reader harder because he just entered this world and quickly forgets much of what he's been taught, which can happen when you're caught in high-pressure, unfamiliar environments. It's what happened to me.

I have four brothers, two parents and loving friends who have always given me solid advice, but due to vanity, ignorance and plain stupidity, I didn't always listen to them. This brings to mind graven images, people mistaking a finger pointing at the moon for the moon itself, and all of those other metaphors for just how hard it is to discern what's real from what's smoke and mirrors. But sometimes you need to lose yourself in order to find it. That sounds Hallmark as sh*t, but it's true.

What was appealing about using satire and absurdity as devices?

What was appealing about using satire and absurdity as devices?

When I began writing Black Buck, I was intentional about the humor, some of the absurdity, but not so much the satire--that was a label other people slapped on later, and one that took me a while to accept. At first, I pushed back, because I thought satire wasn't earnest, but now I realize it's one of the sincerest forms of art out there. Speaking to the book's humor is becoming harder for me. It's easy for me to say that I didn't want to write 400 pages of doom and gloom, especially when most people, at least theoretically, know that racism is bad. But it's more than that. I wanted to use humor, from the very beginning, to invite people into the story so that I could prime them for the heavier themes in the book.

However, I'm aware that for some people, the book is just a funny piece of work, and they never think about it more deeply than that. Last year, a friend asked me if I was prepared for the "double read," where some people will feel the palpable horror that Darren experiences, while others will only see the humor in it. To that I said, yeah, but this work is a mirror, and what people see is only a reflection of themselves. I can't control what readers think and feel, and I wouldn't want to.

Black Buck seems primed for a successful television or film adaptation. Did this come to mind when you were writing?

There are some Hollywood things in the works, for sure, but I wasn't thinking about it while writing Black Buck. Of course I had dreams of the book getting into as many hands as possible, and the thought of bringing it to the screen is something I wanted, but it didn't influence my writing. I only spent more time thinking about it when those opportunities began to materialize, shortly after we announced the book deal in August 2019.

For my next works, especially my fiction, I am thinking about it more, but it's not, as much as I'm conscious of it, affecting what I write, how I write, or why I write.

Liberation is a big theme in your book. How do you see the role of literature, both writing and reading it, in liberatory practices?

Damn, this is a good one. People often describe good fiction as "transporting," which is a liberating act itself. "Escape" is another word. As I'm thinking through this, I'm like, "Yo! This question is big!" For me, writing is when I feel the freest. Full stop. And that feeling--of limitations being defined by my own ideas and ability, or lack thereof--helps me in other parts of my life that are less in my control.

One of the best parts about reading fiction is that it can act as a simulation to experience things you otherwise wouldn't or haven't, which has the power to help you live better. With Black Buck, I didn't want it to be an escape; in fact, I wanted it to take the reader hostage and show them just how real reality is. I was hoping that those who have had experiences like Darren--of being the solitary "other"--would be able to breathe a little easier, at least for a moment, knowing they're not alone. Peace, even if fleeting, is a form of liberation.

Furthermore, I wanted to put together a blueprint of sorts, so that those who are struggling professionally, emotionally, mentally and in many other ways--given how sour the American pie is for some people--would be able to gain a few actionable tips on how to improve their situations. This was my boldest aim, and only time will tell if I've achieved it. --Shannon Hanks-Mackey, writer and editor