|

|

| photo: Marina Waters | |

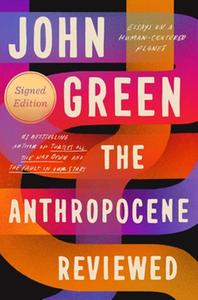

John Green is the author of the novels Looking for Alaska; An Abundance of Katherines; Paper Towns; The Fault in Our Stars; and Turtles All the Way Down. He is also coauthor, with David Levithan, of Will Grayson, Will Grayson. He received a 2006 Michael L. Printz Award, a 2009 Edgar Award, and has twice been a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Green's books have been published in more than 55 languages, with more than 24 million copies in print. We discussed via Zoom The Anthropocene Reviewed (out now from Dutton, $28), his collection of 44 essays that began as a series of podcasts by the same name, in which Green "reviews different facets of the planet on a five-star scale." He lives in Indianapolis, Ind., with his wife, Sarah, and their son and daughter.

There is an art to shaping a 2- to 4-page piece that contains a truth about our current geologic age, the Anthropocene. Is it the kind of discipline that, once mastered, becomes a rhythm for you as a writer? Or does each piece take some sculpting or whittling every time?

My process has always been writing too much and then deleting as much as I can. So with these essays, I wanted to learn as much as I could about the topic, but then I wanted to focus on the places where I could respond personally to the resonances of the subject matter. That involved a lot of cutting away, trying to find the essential story, the essential connections. And now that's one of my favorite parts.

I think the cliché is true, that all writing is rewriting, but rewriting for me is where I find the most joy. Each thing was like taking a really big subject and kind of cutting away at it until it made a shape that made sense to me.

I'm thinking especially of a piece like "Auld Lang Syne" or "Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance," where you're playing with time. Your endings often leave off with a sense of surprise that's so satisfying and often provide unexpected emotion.

I wanted to structure ["Auld Lang Syne"] and a few of the other essays in a way that acknowledged time, acknowledged that we usually tell stories chronologically, but I wanted to write about it in its emotional chronology. For me, it was important to say early on in that essay that Amy Krouse Rosenthal is dead because I didn't want Amy's presence in the essay to be used as a narrative device.

I wanted to end the piece by writing about her work and her life, and how she transformed the mundane, or even the despairing, into wonder and hope. That aspect of her work has influenced me so profoundly. She was a mentor to me. I have tried to take what I have learned from Amy about reckoning earnestly and unironically with hope into my work. It's a place where I feel like my work responds very directly to hers.

Her impact has resonance in other pieces of yours throughout the book.

Yeah, for sure. I started writing the essays that became the book when I was recovering from this very unpleasant--although beautifully named--disease called labyrinthitis. I couldn't open my eyes for almost two weeks, I couldn't play with my kids or read or watch TV or do anything, really. When I started to get better, one of the first things I did was reread a lot of Amy's work. I didn't know if I wanted to write at all anymore. I really felt like my attention had become so fractured and my life had become so loud with all these inputs from lots of different directions and from social media.

And I came across something Amy wrote: "If you want to know what you need to do in life, all you really need to do is pay attention to what you pay attention to." And that was critical for me in thinking about how to begin writing this book, that the book was going to be a way of me trying to pay attention to what I pay attention to.

Can you talk a bit about the subtle differences between writing a script for the ear versus a phrase for the eye? Were you tempted to play the song "New Partner" in the podcast, for instance?

Can you talk a bit about the subtle differences between writing a script for the ear versus a phrase for the eye? Were you tempted to play the song "New Partner" in the podcast, for instance?

You know, it's funny, I always feel like songs are better in podcasts when they're not in the podcast. There are a few examples of this, where I find myself listening to the song when the essay is about a song during the podcast, and I'm like, it would kind of be better for me if you hadn't put the whole song in, because I don't actually like the song that much, and I'm not sure I agree with your breathless adoration of it. I'd rather just hear about what you love and how you love it than be asked to also love it in the same way.

And that's why I wanted to include, at the end of that essay, Sarah and I playing "New Partner" for our son and him not really liking it. I wanted to make room for readers who might listen to it and be like, "Yeah, it's okay. I don't know that I would like, you know, write an essay about it or anything." Because of course, everybody has a different song that can perform that magic for them.

Well, the essay did send me to the song. On the other hand, for "You'll Never Walk Alone" you did include a musical phrase from it in the podcast.

We included the singing of the paramedics through the window, trying to sing their colleagues in the ICU into courage and comfort.

And that leads us to the sports pieces, and the way "You'll Never Walk Alone" figures in your piece about Liverpool goalie Jerzy Dudek. You give readers just enough scaffolding if they've never seen a Liverpool football game to understand the impact of the individual player's story. How do you do that, inform in a way that brings us inside of the experience rather than distancing us from it through instruction?

I try to build enough support for the reader that they don't have to like soccer, or even know soccer, to care about this moment when a goalkeeper made an extraordinarily strange and beautiful choice. And that's what I'm always trying to do when I write about sports--I want people who don't care about sports to be able to glimpse why people who love sports, love them.

I can be deeply moved about all kinds of things that may not be things that I have a natural affinity for because of the way the story is told. And that was kind of the challenge I set for myself with the sports chapters. My wife enjoys watching soccer, but it's certainly not a big part of her life, the way it is for me. The way I thought about the Jerzy Dudek essay was: How can I write this in a way that will bring a tear to Sarah's eye and help her to understand why this matters so much to me?

The same is true when you describe the Bonneville Salt Flats. You put me there, and I appreciated their vast whiteness. Was it more challenging to do that for a place than for a set of circumstances?

In some ways, yes. With the Salt Flats, I wanted to take this color that we have certain associations with, and associate it with the blankness, with the threat, like Melville did--the "colorless all-color." But I also wanted readers to be able to feel, almost sense, the lack of sensation there; other than being able to smell the salt, you do feel extremely lonely. Even though there are lots of people around trying to angle their selfies so that they can look extremely lonely. But you do feel it, you feel the geography, and that's something that has interested me for a long time.

It's hard to imagine being at the Bonneville Salt Flats and feeling anything other than lonely and feeling anything other than being pulled away from your life, away from your world, toward these traumatic memories, and toward the stuff that you thought you had survived but it turns out you still live with. And then to be pulled back by my spouse was a really powerful moment for me. So I wanted to try to capture that moment.

One of my favorite pieces was "Indianapolis." It's a demonstration of how listening to someone you care for, in this case your friend Chris, helps open our eyes to the beauties we might have overlooked. And that happens again with your son in "Sycamore Trees," and with your daughter in "Whispering."

I learn so much more from my kids than they've learned from me. And one of the main things I've learned from them is that wonders are never far away. It's my ability to notice them, to give them the attention that they demand, that's often far away. And Chris, my best friend, reframed Indianapolis for me in a way that changed my life, because that's the reason I'm still here. And my brother [Hank] reframing human life for me over and over and over again, over the last 40 years, has been critical to my ability to go on, and to enjoy life and to find and seek awe in the world. If Sarah hadn't reframed the whole concept of this book for me, after I wrote the first two essays, by telling me that I couldn't pretend to be some objective expert on the subject of Canada geese, and instead needed to acknowledge that I was not an observer of the Anthropocene, but instead a participant in it, the book would never have happened.

I wanted in the book, over and over again, to go back to the idea that we accomplish almost nothing in isolation. We have always been a deeply collaborative species. And while we celebrate the stories of individuals and their individual discoveries, that's almost always an oversimplification. The truth is almost always that discoveries and innovations are made by people working together. I wanted to find lots of different ways in this book to write about the power of human connection. Because I have experienced that, and also because, in the last year and a half, it's been something I've desperately missed. --Jennifer M. Brown, senior editor, Shelf Awareness