_Bear_Guitirrez.jpeg)

|

|

| (photo: Bear Guitirrez) | |

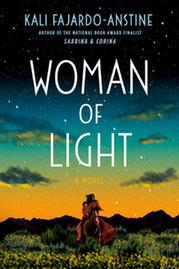

Kali Fajardo-Anstine is the author of the story collection Sabrina & Corina (One World, 2019), winner of the American Book Award and a finalist for the National Book Award, the PEN/Bingham Prize, the Clark Prize, the Story Prize and the Saroyan International Prize. She is the 2021 recipient of the Addison M. Metcalf Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the 2022/23 Endowed Chair of Creative Writing at Texas State University. Her debut novel, Woman of Light (reviewed in this issue), is a multi-generational epic reaching back to the 1800s through 1934 and primarily set in Denver, Colo., where she lives and worked as a passionate bookseller.

What does it mean to feel a deep connection to a place and its history? How does it manifest in your visions for life and what you write?

When I lecture on place-based writing, I tell people that place is an extension of consciousness. Place is so steeped in my work because it is the nature of place that created a person like me. I am multiethnic. I am a Chicana of Indigenous ancestry, Filipino, Jewish, white, American. Why I exist is because place brought all those people together in Denver and so if I removed place from my work, there would be no characters.

When I read your work, I'm struck by the presence of mystery. How do you use mystery to point toward truth?

In a lot of ways my entire existence was built out of the mystery of not fitting into a category, and that's why I'm comfortable with mystery--I want to unnerve the reader, I want them to think about what they do not know. And I think it's a particularly American trap to think we know more than we do.

I just read this gorgeous book, Bitter Orange Tree by Jokha Alharthi, the first Omani woman to be translated into English. And there was this beautiful reference to these women who make charcoal. They live at the edge of the city. I had no idea that there was a whole process to make charcoal. I didn't even know it could be a gendered job, and at first reading that I could have assumed that that author didn't know what they were talking about, I could have assumed that this was fantasy or I could have assumed that this is an entire industry and tons of people do it, but instead I just read it for what it was--a part of the story--and I absorbed it.

Is writing rooted in creation and inspiration or observation and interpretation of the world around you? Both? Neither?

It's both for me. The writer Jayne Anne Phillips once told me that there are two different kinds of writers: those who write to make something new and those who write to keep something from disappearing. Recently the Chicano murals of Denver were named one of the 11 most endangered historic items in America by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. We're being displaced, and to me the act of writing was a way to put us into the historical record through literature.

And literature is also a way to imagine new possibilities. I write naturalistically, in ways that do not pander to a white gaze or exotify my characters.

In a lot of ways being a writer is being very porous. You have to be very sensitive and I don't know if that comes from direct observation or from looking within--the more mystic approach to it--but one thing that both sides have in common is it's a deeply reflective, almost meditative act.

Time is such a character in Woman of Light. How, especially compared to writing a short story on a practical and technical level, do you approach time?

Time is such a character in Woman of Light. How, especially compared to writing a short story on a practical and technical level, do you approach time?

Making sure Woman of Light had this enormous scope from the 1860s all the way into 1934 was vital. This is when my ancestors went from having rural lives to leaving their pueblos and having an urban lifestyle. This happened in one-and-a-half generations.

Another way time is really fascinating is if your ancestors have been in place for multiple generations. When I look at a street corner--for example, where Luz works in Woman of Light with David--I not only have my own memories of that place, I have the stories from my mother. I have the stories from my grandfather, and I have the stories from my great-grandmother and those all seeped in, and so it flattens my experience of time. A huge amount of generational knowledge was passed down to me orally. Sometimes we think of our knowledge as only being for one generation at a time, our own lifetime, but in fact it spans many, many decades.

Do you think about Woman of Light as more like a painting, something with a direction but most truthfully represented as happening all at once?

Its order is something I found later. Time for me is experienced in this huge circular cloud that I'm inside of. I learned to trust moments and scenes in a way that I had never trusted them before. In a short story, I'm usually going through point A to point B to point C, but with this novel I took down scenes and moments as they were coming to me rather than forcing myself to go through the path in a linear way.

What are you looking forward to in 2022?

I'm looking forward to this move to Texas for a new job at Texas State. And I'm looking forward to publishing my first novel! It's simply mind-blowing that a book based on my ancestors, people who weren't literate, is going to be out in the world and bookstores and on shelves. So I'm really looking forward to that experience and for the world to know who we are and to learn about us.

The book took 10 years to write and a lot of that was spent doing research--archival research, listening to oral histories, interviewing my elders--and the book is filled with references to Denver history as well as history of the American West. They're all Easter eggs, right? Good luck to everybody who finds them! --Walker Minot, freelance writer and editor