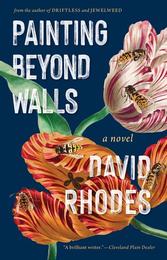

David Rhodes's acclaimed debut novel, The Last Fair Deal Going Down, was published in 1972, the year he moved to the Driftless area of Wisconsin, where he remained for more than 40 years. He now lives in Madison, Wis. The Driftless area was untouched by the last glaciers, and thus "the roads don't go straight and the farming hasn't been utilized for large-scale agriculture," Rhodes explained. His sixth novel, Painting Beyond Walls (reviewed in this issue), is set in this area, slightly in the future: August Held returns to Words, Wis., after being fired from his Chicago laboratory, to discover a wealthy enclave, Forest Gate, encroaching on his hometown.

David Rhodes's acclaimed debut novel, The Last Fair Deal Going Down, was published in 1972, the year he moved to the Driftless area of Wisconsin, where he remained for more than 40 years. He now lives in Madison, Wis. The Driftless area was untouched by the last glaciers, and thus "the roads don't go straight and the farming hasn't been utilized for large-scale agriculture," Rhodes explained. His sixth novel, Painting Beyond Walls (reviewed in this issue), is set in this area, slightly in the future: August Held returns to Words, Wis., after being fired from his Chicago laboratory, to discover a wealthy enclave, Forest Gate, encroaching on his hometown.

Words, Wisconsin, is a fictional place, isn't it? Was it inspired by a town you know well?

Yes, it was. I lived a little ways out of Wonewoc, Wis. I felt very blessed--we moved there in 1972. It charmed me to death. There were 50 or 60 people living there, and they welcomed us, even though we were outsiders. It gave us a glimpse of an earlier way of living. I made a lot of really good friends there. My whole life kind of rolled out there.

I wanted to purposely take on the rural/urban divide and try to point out some of the endearing features of living in a rural area that are often overlooked. I wanted those to be experienced through the main character when he returned from living in the city for awhile. His sensibility would be somewhat sharpened. He makes the ultimate decision to stay, partly out of a sense of loyalty, and partly out of a decision of compromise between a professional life and a less professional life.

August picks friends who are self-actualized: Ivan and Hanh really know themselves. They wind up being a compass for him. Did you start out with that dynamic in mind? Or did it develop as the novel developed?

A little of both. I had their development from the earlier books [Driftless and Jewelweed]. I wanted to expose August to an example of nonpossessive love, and Ivan and Hanh seemed like good vehicles for that, to give August a new way of looking at what type of relationships were possible. And having that contrast between his relationship with Amanda [his wealthy Chicago girlfriend], and Ivan's relationship with Hanh--it was both evolving and also I'd thought I needed to do that from the beginning.

The relationships August has with Amanda Clark and April Lux revolve around class. Do you see August as a kind of human embodiment of what's happening in his town, with the wealthy encroaching on this idyllic, modest lifestyle?

I wanted very much to have that contrast be highlighted. August first experiences Forest Gate through his friends. He runs into the prejudices of Ivan and of Lester, and to some extent Hanh. Then he vocalizes that prejudice to his mother, and she says, "Why would you feel that way about them, how would you want them to act? They're rich, why shouldn't they have these things? You're judging them; you don't know them at all." I wanted to have that clash of classes. I've been prone in my own life to think, oh, that's a rich person, as if that means anything in terms of character or values, because I grew up in a working-class environment. It's just someone living in different circumstances.

But there's another aspect here, too, which comes up after August has sex with his childhood crush, Hanh. Ivan left and allowed August and Hanh to complete what they'd left incomplete before August left for college.

But there's another aspect here, too, which comes up after August has sex with his childhood crush, Hanh. Ivan left and allowed August and Hanh to complete what they'd left incomplete before August left for college.

That made Ivan into this character that was much more thoughtful and circumspect than you would normally imagine he would be.

What I wanted to try to do with the book was to encourage readers, or share with readers, that our intuitions, our instincts need to become entirely conscious in order for us to make choices about how to live in an ethical and happy way.

If they're not conscious, if we just act instinctually--when August says, I'm not feeling these things; my ancestors have given me these feelings--and you're not able to distance those from you, we don't live as full a life as we could. We need to make as much of our feelings as possible completely conscious. When our instincts become well-examined, we have more choice than we think we do.

Readers also get a window into the intimate relationship between Winnie and Jacob, August's parents, when he overhears them upon first returning to his house.

I could picture that scene so clearly when I started the book, where August's father had pulled the car he wanted to work on out into the garden where his wife was working so they could be together. They're totally different people with totally different interests who loved each other. I had Winnie in a nuanced discussion about how a particular prayer would work, and then her husband talking about the car he was working on. I had the most fun writing that scene.

The contrast between Ivan's time away working on the pipeline and August's time away in Chicago at first seems dramatically different. But as the novel develops, readers learn they were quite similar in terms of what both men learned about the world. Do you believe one needs to leave a place to know themselves?

I think you gain new perspectives by leaving the place you grew up in. I'm not sure that that means you can't have a fulfilled life without doing it, because that was one of the things I experienced when I first moved to the Driftless area.

I met some people who'd never been more than 20 miles away from where they were born. And they had perfectly well-rounded lives. The depth of knowledge concerning the people and place that they lived in was so profound that I think in a lot of ways it would fill their lives out just as much as a different perspective. It doesn't need to be judged as better or worse.

I interrogated myself in that way over Winnie--when she knew all about August's college roommate from Pondicherri, India, and the yogi who started an ashram near him, and then making August's roommate the perfect gift.

Isn't that something you have to learn over and over, not to be judgmental and not to ground your impressions on earlier things that those impressions remind you of? You form opinions and generate feelings around certain things, and when you run into those things, they bring up old feelings that don't belong in that environment. The things you learn when you're young don't always apply. You've got to relearn new rules. --Jennifer M. Brown, senior editor, Shelf Awareness