Oliver Jeffers is a visual artist and author working in painting, bookmaking, illustration, collage, performance and sculpture. A professor at Queens University Belfast, Stephen Smartt is an authority on exploding stars and unusual transients in the universe and runs large sky survey projects to stretch human understanding of how stars die.

Oliver Jeffers is a visual artist and author working in painting, bookmaking, illustration, collage, performance and sculpture. A professor at Queens University Belfast, Stephen Smartt is an authority on exploding stars and unusual transients in the universe and runs large sky survey projects to stretch human understanding of how stars die.

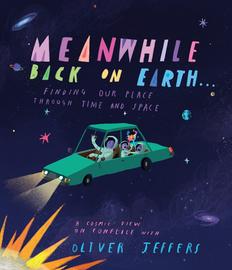

Earlier this year, Jeffers teamed up with Smartt to explore on a large scale "the Earth's fragility and humankind's shared responsibility to protect it." Our Place in Space is a 10km scale model of the solar system and walking trail that is a collaboration across art, science and technology. Jeffers's 19th book as author and illustrator, Meanwhile Back on Earth (Philomel), highlights the concepts of Our Place in Space in picture-book form. Here, the two discuss their collaboration and the inspiration behind both projects.

Oliver Jeffers: The first question we were asked, when we partnered to create Our Place in Space, was what can we in Northern Ireland contribute that nobody else can? Out of this sentiment came the idea of speaking with authority about the negativity of the divisions of "us" and "them." Separately, I had been looking at scale and perspective, and the idea of doing a scale model of the solar system. So, taking Northern Ireland as the framing device for looking at how we divide ourselves over vast distances became the foundation of this project.

Stephen Smartt: And for years, we as scientists have been trying to communicate concepts like vastness, but largely thinking of it from a scientific perspective rather than a humanity perspective. The questions I am often asked are, "So what?" and "Why should I care?" As we're finding things out about the universe, how does this apply to the everyday person in the street? Our Place in Space helped me with such questions.

|

|

| Oliver Jeffers | |

Jeffers: And you said multiple times doing the trail, it was the first time that you've not really needed numbers. It just clicked into place. People are spatially aware, so you can sense distances, the scale and scope. It's a 591 million-to-one scale model. Why is it that size? I guess that's as small as we could make it?

Smartt: Or as big as we could make it and people would still walk the full trail. What we initially wanted was people to get a feeling of the distances between the planets, and the size of the Earth within this. It's precious, delicate. But if we made it too big, we would have lost that.

Jeffers: And any smaller, the Earth would've been invisible to the naked eye.

Smartt: Yes, there's a limit. In our scale model, the Earth is only 2cm in diameter. Pluto is the size of a match head. Going any smaller would've been difficult.

|

|

| Stephen Smartt | |

Jeffers: One of the fun things about it was working out comparative scales. For example, figuring out you were walking at around one and a half times the speed of light along the trail. You worked it out really quickly... it takes light eight minutes to reach the Earth from the Sun. On the trail, you can walk it in around five minutes.

Smartt: It was pretty satisfying seeing the scale work! So then, where did Meanwhile Back on Earth come from during our work on Our Place in Space?

Jeffers: We were looking at this not only as a scientific project but also an art project. You start at the Sun, move toward Earth, then once you pass Earth, how do we keep people looking back at the Earth? The goal was not to get to Pluto, but to continue looking at humanity's place within our solar system. Nobody knows what the speed of light looks or feels like. But we do know what it looks and feels like to drive a car. And so, the idea became how long would it take to drive at 37mph to each planet from Earth? Like Our Place in Space, it comes back to the concept of "us" and "them." We realized the amount of time it takes to drive to each planet could be a good measuring stick for looking back through Earth's history. It's impossible to look through the past and pick a year where there wasn't some all-consuming battle taking place over territories.

Smartt: We initially thought "we'll have to go in a spaceship for these time scales to work!" But just get in your car. And as you said, you get a feeling for the time and speed. And by coincidence, the distances between the planets map on to hundreds of thousands of years of human history.

Jeffers: Well, that's exactly it. In the book it's 37mph--we know what that feels like. It puts us back to 11,000 years ago from Pluto, which is pre-civilization.

Thinking of the notion that with distance comes perspective, and the subtle point that the only time there wasn't an all-consuming conflict was 11,000 years ago... People were too busy working together to try and survive the elements... rather like what we should be doing today! Hopefully this book can help speed that along.

Smartt: Framing it with human conflicts was a great idea. The current conflicts are starting to not make any sense--we're at a time that we just have to try and survive together. Thinking of human history, our minds usually go to a battle/conflict or human achievement. Human achievement generally happens when people work together. Our history is dominated by conflict, but it shouldn't be when we look at what we've achieved.

Jeffers: You said it best. When we divide ourselves, problems happen. And uniting ourselves is when we tend to solve problems.

Smartt: It is part of our duty as scientists to tell people about what we do, communicate it, get kids interested and involved. But this project has been the best. We've reached so many people, and it's the art and science together that has been the game changer. So, let's absolutely do something together again.

Jeffers: Well, looks like we have to find another problem to solve!