_Becca_Farsace.jpeg)

|

|

| (photo: Becca Farsace) | |

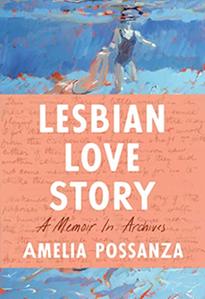

A full-time book publicist and part-time writer, Amelia Possanza lives in Brooklyn, N.Y., with her cat. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, BuzzFeed, Electric Literature, the Millions, and NPR’s Invisibilia. In her first book, Lesbian Love Story: A Memoir in Archives (Catapult, $27; reviewed in this issue), Possanza investigates seven queer romances in history, with figures such as Mary Casal, Mabel Hampton, Babe Didrickson, and Sappho, as a way to better inform her own modern understanding of what it means to be a lesbian.

How did you decide on these seven relationships?

I wish I could say that there was a really specific process. There were definitely moments where I was deciding to look at one person, only to find out that there's no there there. For a long time I was interested in my hometown, Pittsburgh. Gertrude Stein lived there for three months when she was a kid, but that was clearly a dead end. So, what remains is what was fruitful. I'm interested in how people fall into gender roles even in non-normative relationships, and those relationships were easier to find, because it was their lack of normativity that landed them in jail and generated a record, or got them called "female husbands" in newspaper headlines. There had to be something "wrong" or "off" to create a historical record, and I think the more you conformed, the more you could just skate through.

Do you think the Internet, where we document ourselves more, allows us to parse finer nuances in those gender roles?

We just have so many words for it now. Mary Casal didn't even have the word "butch." That comes up in the second chapter, in Mabel Hampton's life, and she adopts the role of the butch or the stud in the relationship; her partner, Lillian, was more femme, a "wifey." But even then, style was limited by the law in a lot of ways: she couldn't wear pants.

We also have more places to look at each other, like on Instagram. There's that community aspect to the Internet. Mary Casal spent a lot of her life thinking she was the only person who was interested in having a woman as her partner. She didn't have anyone to look at and learn what the hip lesbians wear--carabiners, Birkenstocks. It wasn't a cultural thing, so she created a lot of it on her own and she did find those people, but it meant something different to her. It was more private. And she looked down on other queer people, especially male queer people and those who were promiscuous.

It reminded me of something David Halperin writes in How to Be Gay, basically about the process of becoming who you already are. Your book seems to delineate a lot of the lesbian counterpoints to Halperin. For example, Louisa May Alcott isn't a chapter header, but you return to her a lot. What sparked your interest in her?

It reminded me of something David Halperin writes in How to Be Gay, basically about the process of becoming who you already are. Your book seems to delineate a lot of the lesbian counterpoints to Halperin. For example, Louisa May Alcott isn't a chapter header, but you return to her a lot. What sparked your interest in her?

Like what you were saying about defining gayness, I feel like so many young girls define themselves through Alcott's work. Talking to a queer friend whose cat died unexpectedly, she said the cat was the runt of the litter, "She was a real Beth." It's like a metric to measure who you are by.

So much of why I read, and why I read when I was little, was because I wondered what life was going to be like. What does a lesbian life look like? Had I read a novel with a lesbian protagonist at that age? No, but I had Little Women. And that set up, for women of the era up until now, what life was going to be like: you got married; you rebelled and had an intellect, but you still got married; or you died! Those are the options in that book.

And then I found that quote about how she's half persuaded that she's a man--there's the gender thing--but then it's conflated in her era with sexuality. She said she'd never been in love with a man, but there are so many pretty girls who have her heart. I realized she didn't have the words to talk about what was going on with herself. Himself? There's something that's lost there, and some people have made a very strong argument that Louisa May Alcott may have been a trans man, who went by Lou, and wanted to write. I'm not here to make that decision for anyone; I'm of the opinion that there are some people we'll just never know about.

A big part of my project is asking: What did the word "lesbian" mean over time? At the moment she was alive, that word might have been fitting for her, just because that was all that was understood. But I want to be very clear that this isn't the history of lesbians as they are now, but instead asking what this word has meant. Louisa May Alcott was a person who was in the orbit of that word--which came from Lesbos--but we have no way to know. Our conception and our understanding of gender and sexuality can't be mapped onto people who lived in different eras.

You write about taking your time in deciding on that word for yourself, eventually identifying with "lesbian" in college. How has that word evolved for you over the course of your research?

To me, it's almost become a ridiculous word. In college, I thought it was great, but then growing up I feel more complicated. I don't want to associate myself with the lesbian separatists of the '70s. I don't want to have essentialist ideas about who's a woman and who isn't. Some people have switched to "Sapphic" as a way to expand that definition. But I also love that "lesbian" freaks people out. There's no other word like it. Everyone just looks horrified when they hear it. It can generate a laugh even if there's no joke. There's a line in that movie Bend It Like Beckham where the mom of one of the girls says, "Get your lesbian feet out of my shoes!" And the whole joke is that she has said the word "lesbian." So, I've come back around to think of it as a great, silly word that can freak people out but also mean a lot of things. The OG lesbian, Sappho, had a husband! This idea of purity feels like a really recent one.

There's a tension there, right? Between wanting to be visible and recognized as this outsider identity from the mainstream, even though that identity is a dangerous one. Why is that visibility so important when it also makes us targets?

This goes back to your question about why these seven pairings. When I started this project, I was really angry because I know about all these gay men in history, so I thought I'd write an essay about how gay men take up so much space. But I quickly realized that I wanted to find these lesbians that I haven't been hearing about, instead of getting hung up on my resentment.

Early on, people asked if I was going to write about Emily Dickinson and Eleanor Roosevelt, these very famous people who have a lot of speculation around them. But I was much more interested in exactly what you're talking about: Who are the people who aren't remembered for the usual historical reasons? Who are the people who risked it because they wanted to live a different kind of life than what was prescribed for them? The farther you go back, the more that risk was taken, not just because of an intense sexual attraction or internal gender identity--that was definitely part of it!--but the other part was the roles that women were offered were so limiting. I think a huge part of the risk was wanting to reject the prescribed life for women of the era, and replace it with a life centered around different values.

Like, what was Mabel Hampton famous for? I think she's incredible because she helped to found the Lesbian Herstory Archives, taking care of the stories of so many of her contemporaries in the Harlem Renaissance. Mary Casal, before she met Juno, was an inventor. She didn't want to be a wife and a schoolteacher. Joan Nestle (of the Lesbian Herstory Archives) said it best, when we talked about the idea of fame, that taking that risk "is fame enough." That risk being touching other women, which is the language that Joan uses for it, but for me it's the risk to define life on your own terms.

Your book really illustrates how lesbians have cared--for their stories, for each other, for gay men during the AIDS crisis. And I was struck by the way you show your own form of care by inlaying text from your primary sources, creating something like a palimpsest. How did you decide on that format?

A big part of it was that the first person I found was Mary Casal. I read her memoir and realized that she was saying that she was in love with women. We don't have that from Emily Dickinson or Eleanor Roosevelt in the same way. Yet I never knew that this person was out here at the turn of the century, saying, "Here I am, in a relationship with a woman." It's wild.

I also didn't want to be labeling people as queer who did not self-identify that way. Using their own words was important to me, to show that I'm not guessing that these people are queer. I'm not making up the way they talk about their passion or their feelings or their gender roles. Being a stud or a wifey--I never would have known that "wifey" was the word people used in the '40s and '50s to talk about their femme partners.

In a nerdy way, too, I'm so concerned with the archives. I don't want to be the only one looking at this stuff. My dream is for other people to find their own role models. If we had more of these stories as our inspiration, what would our world look like? --Dave Wheeler, associate editor, Shelf Awareness