|

|

| (photo: JP Calubaquib) | |

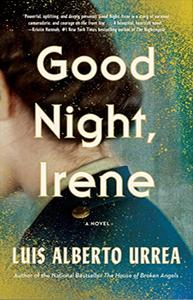

Poet, novelist, and nonfiction author Luis Alberto Urrea was born in Mexico to a Mexican father and an American mother. He has won multiple literary awards, most recently for his 2018 novel The House of Broken Angels. The Devil's Highway, a nonfiction narrative of Mexican immigrants lost in the Arizona desert, was a 2005 Pulitzer Prize finalist. His ninth work of fiction, Good Night, Irene (Little, Brown; reviewed in this issue), inspired by his mother's service as a Red Cross "Clubmobile" worker in World War II Europe, follows the women who provided donuts and hope to the troops, forging friendships as they cheered the soldiers while enduring the horrors of war. Urrea and his family live in Naperville, Ill., where he is a distinguished professor of creative writing at the University of Illinois-Chicago.

You are well known for your writing on Mexican American themes, especially The Devil's Highway, and your novel The House of Broken Angels. Good Night, Irene, is set in WWII Europe. What inspired you to pursue this topic?

My mother. This is the heroic epic that her service in the Red Cross called out for. In my work, I almost always honor my family and my culture--my mother happened to be the only American in a sea of Mexicans.

How was writing a novel based on your mother's experiences different from shaping characters in earlier novels?

The characters in this novel are shaped characters--it's a work of fiction. That being said, like The Hummingbird's Daughter, it is grounded in real history, real places, and a true timeline. The characters in the novel are imagined; however, they are shaped, colored, and nuanced by my mother and her war buddy Jill. If you keep an eye open as you read, Phyl and Jill make cameos in a couple of places. My subliminal way of saying "this story is about Irene and Dorothy."

In my earlier novels, I was generally in a pretty specific place/time, peopled with specific characters. The fun thing in this World War II milieu was I had a lot more freedom because anybody could be from just about anywhere. For example, I pretty freely populated my created universe with the veteran grandparents and parents of friends and readers who shared their stories with me.

Good Night, Irene is rich in dialogue, much of it including 1940s references and slang. How did you research the language of the era?

Good Night, Irene is rich in dialogue, much of it including 1940s references and slang. How did you research the language of the era?

Drove my editors crazy! Fortunately, they are obsessive compulsives, and they helped weed out slang that might have been from the '50s. There are many available websites of slang from different decades in the U.S., and I have a wonderful dictionary of military terminology and slang called FUBAR. But of course, I heard some of it from my elders as a boy. The best was the time my wife and I spent with the only surviving Clubmobiler, Jill Pitts Knappenberger. We both basked in that palaver in Jill's apartment.

In your novel, Dorothy describes a group of soldiers of diverse backgrounds, saying, "Ain't we a bunch. Ain't we America." Was your characters' diversity significant?

Absolutely. I felt it incumbent upon me to represent the best dream of democracy in the face of fascism. It was both a celebration and a warning. When you begin to look into WWII, you find every ethnicity, every political view, every accent, every color. Sometimes struggling with the prejudices of the day, sometimes segregated, yet learning that, under fire, we were all Americans. It was a profoundly human message. Thus, the Latino and other soldiers of color, Indigenous, immigrant, midwestern farmboy, beautiful rabble that populates the novel. On a personal note, I was heartened by how many Mexican-American soldiers fought for our country.

I did the bulk of the writing of this novel during the turmoil of the last few years and this was my small way of offering a corrective to the divisions and polarizations of this era.

Reviewers have praised your works for evoking contradictory emotions. Viet Thanh Nguyen cited The House of Broken Angels as showing "love and pain, joy and resentment, hatred and reconciliation." Your new novel prompts tears of both sorrow and joy. Do you consciously craft these opposites?

Isn't that the human condition? If it were all giggles or all torment, it isn't honest. Even the profoundly dark and hopeless novel Under the Volcano by Malcolm Lowry is hilarious. The light and the shadow bring each other into better focus and poignance. On a craft level, I would say there are precipitous falls into horror and despair in my book. And as a composer, I strive to ease the readers out of the abyss so that the story can continue, much like those women did. They did not become goths. They used their spunky personas to pick up and move forward.

This novel, as well as The Hummingbird's Daughter, have exceptionally bold women protagonists. As a teacher, what would you advise your students who might question their skill at presenting a perspective they can't experience?

I tell my students we are here to bear witness. If you bear false witness, it is a sin.

You'd better make sure your eye is well-calibrated and focused; you'd better make sure that your prejudice and power of assumption is dialed in and not spouting propaganda, rhetoric, or opinions. Not only do you need to know what and who you are talking about, you need to know that you are not furthering toxic, inaccurate canards.

These people, these genders, these ethnicities are not tropes. We have all suffered this sort of toxic thinking long enough. You'd better check yourself. If you have a trusted representative of whatever group/gender/ethnicity you are exploring that you can give your work to for an opinion, do it. If you don't, or if you are nervous for them to see it, you are in the wrong game.

People have been treated with enough disrespect and condescension to last us for all time. This may make me sound like a hippie, but I am dead serious about this: I tell my writers "Fill your pen with love or don't bother picking it up." And I suggest they take a long hard look at what the word "love" means to them. I would begin the definition with "respect."

You are accomplished in many genres. How does your approach to composing in different forms vary?

My new book of poetry, Piedra, just published this month, and it was something I was working on even as I was working on this novel. At the same time, I was working on a nonfiction piece for a major magazine about the lives of Mexican migrants working in the heartland without documents. I don't want to say that I live in my notebooks, but... I live in my notebooks. One of my models early on was Leonard Cohen, who wrote songs, poems, and novels. I knew right away that was the kind of writer I wanted to be. It all fascinates me. As precious as this may sound, to me, writing is prayer.

Of course, there is a difference between a whopping historical novel and a haiku. But it is about one's engagement with this life. My joke I share with my workshops when this question comes up is: if you are moved by dewdrops on the face of a sunflower, it's probably a poem. If your mother was an unsung hero of WWII, it had better be a big fat book. --Cheryl McKeon, Book House of Stuyvesant Plaza, Albany, N.Y.