|

|

| (credit: Stephanie Ewnes Photography) | |

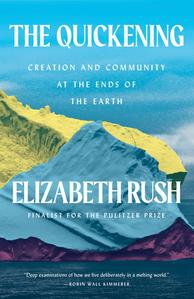

In 2019, Elizabeth Rush was invited to join the scientists and crew on an unprecedented expedition to Thwaites Glacier, a never-before-explored part of Antarctica. From that experience comes The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth (Milkweed Editions; reviewed in this issue). Similar to Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore (finalist for the Pulitzer Prize), The Quickening looks unflinchingly at the difficult truths of climate change and the complicated decision to become a parent at such a time. Rush lives in Rhode Island, and teaches creative nonfiction at Brown University.

For a book ostensibly about a scientific expedition, The Quickening takes an unusual structure and slant, incorporating a surprisingly high volume of dialogue. What made a four-act "play" the right form for this story, and why was it important for the "cast" to speak in their own voices?

It's a choice that I can trace to a single book. I don't know if you know Ilya Kaminksy's book Deaf Republic.

I love that book.

It's such an incredible book. It's a collection of poems about a community living through a repressive regime, and at the start, there's a cast of characters. For instance, you see something like "Sonya, pregnant, puppeteer." There was something about that structure that made each character feel like an autonomous, fully formed person, like I was being invited into this community.

I wanted to try that structure in this really different form. My book is not poetry, but I didn't want my shipmates to be experienced through the cipher of me as writer and documentarian; I wanted them to sprout from the page fully formed. So my narration is regularly interrupted by my shipmates speaking, and that's formatted on the page to look like a screenplay. They speak directly to the reader.

You mention feeling invited into community by Kaminsky's book. With all the big issues in this book--Antarctica, climate change, motherhood--it would be easy to miss part of the subtitle: "Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth." But one of my favorite pieces of dialogue is when Gui says of life on the boat: "Every time I need help, I ask, and every day, people help." What do you think might change if our everyday world looked more like this?

As a mother to a young child and before that, being pregnant in the pandemic, birthing a child into a pandemic--one of the hardest parts has been learning to ask for help from my community. I pride myself on being independent. We've been taught it's a valuable characteristic, and as a woman you want to lean into that independence even more. And yet, something that I've experienced--on the boat but also through early motherhood--is that your community wants to help, they want to feel useful. When we don't ask for help, we deny people the possibility of feeling useful and needed. I get that it's hard to do, but it is central to the creation of a community that's interdependent and tight-knit and reliable.

You write, "Some call this moment, and the many others that are piling up, the beginning of the end. Some suspect this is how the insurgency starts, with the rattling of glaciers." Would you call it that?

You write, "Some call this moment, and the many others that are piling up, the beginning of the end. Some suspect this is how the insurgency starts, with the rattling of glaciers." Would you call it that?

I wouldn't say that we're at the beginning of the end. If we take a more ample view of history, we understand that the world is always ending; worlds are always ending. The question is: How do we live through that and become stronger, more whole somehow, on the other side? I would love to think that this is the beginning of the insurgency as well, but I don't think that's a certitude. I think that's very much up to us.

In several places throughout the book, you engage our understanding of time and how our connectedness through time affects how we see the world. It seems like you were trying to pan out and show a longer sweep of history, a broader perspective. Why was this subtle thread an important one here?

Totally! It is so hard for us to think outside of human time. There have been all these psychological studies that conclude we can understand our parents and our grandparents, and we can consider our kids and our grandkids, but beyond those boundaries, it's very hard for humans to get a grasp on time.

So to think about the timeline of trees or glaciers--is that impossible?

I think we can try! I was on the boat with a lot of glaciologists, studying the movement of glaciers 10,000 or even 20,000 years ago, around the last glacial maximum. Or they're looking at sedimentary records around the same time, trying to figure out how Thwaites has acted since the end of the last Ice Age. They are fundamentally aware that their life is a really tiny blip in a much longer range. So I know it's humanly possible.

I remember asking chief scientist Rob Larder if Antarctica shapes us. I thought he was going to dismiss my questions as humanistic sorcery, but he said yes. The last 6,000 years of planetary history have been really stable. If you go beyond that, sea levels regularly rise and fall 5-6 feet per century. Which is what we're facing now, and it's throwing our world into chaos because we're not used to it. We're used to sea level variability being really low in comparison to the standard in geological time.

Your book Rising opens with a simple epigraph from Simone Weil: "Attention is prayer." How do books like The Quickening help us find that kind of reverent attention to the world around us?

In the environmental literature and humanities world, there's a big push for recognizing the animacy of nonhuman actors right now, and I think what The Quickening offers in terms of paying attention is that it is actually a laborious and time-consuming task. I think it sometimes appears cloyingly simple. Like, let's recognize the animacy of trees! But to do that, you actually have to pay attention over these longer time scales. I hope The Quickening is an invitation to think about attention to nature or nonhuman actors as something you foster in the place where your life takes root. It's too easy to think about going on this huge expedition and getting to see these sublime things or climb this mountain. At some level the book is saying it's way more important to hone that attention at home. It talks about the fallacy of only tuning in or turning oneself on in those heightened moments.

You wrestle with the decision to bring a child into this potentially collapsing world, but at one point you suggest having children might be "an act of radical faith that life will continue, despite all that assails it." How do you manage that fine balance between hope and the despair that can set in when we look too long at the facts of climate change?

Part of me thinks you do it because you don't have another choice. There's not an option. And isn't that true of everything that is really rewarding and hard. Everything that's worth it is at some fundamental level not easy. And you wouldn't do it any other way. It's a fallacy to assume that you can have hope without despair or hope without fear or hope without concern. Hope is a tool that propels you to make that world the way you want it to be. --Sara Beth West, freelance reviewer and librarian