|

|

| (photo: Sergio Parra) | |

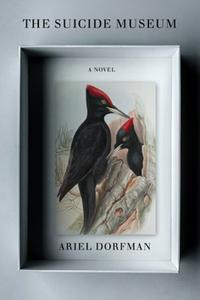

Argentine-Chilean-American novelist, playwright, essayist, academic, and human rights activist Ariel Dorfman has been writing since childhood, with his numerous works appearing in both Spanish and English. Following the 1973 military coup in Chile that ended the presidency of Salvador Allende, he and his wife, Angélica, spent years in exile before settling down in the United States. He is now Walter Hines Page Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus of Literature at Duke University. Shelf Awareness spoke with him about The Suicide Museum (Other Press, reviewed in this issue), his gripping and expansive mystery novel exploring the truth about Allende's death.

Did you always want to be a writer? What made you want to write this book?

I decided to become a writer when I was nine years old. Two events converged: my parents gave me a little red diary to record my experiences on what would be a long trip to Europe. Scribbling words down was liberating, a way of communing with my secret self. The second event was that on that 1951 journey to Europe I met Thomas Mann (I am not kidding). I was anguished at the time by the possibility that our family would have to leave the States permanently. What would happen to the English that was most intimately mine (despite having been born in Argentina)? Mann had the answer: you carried your language with you wherever you went. Being a writer, therefore, gave me stability as I anticipated what would be yet another uprooting.

As to this book, twin obsessions are at its origins. To write a thriller which tried to determine the truth about the death of President Salvador Allende in the 1973 coup in Chile. And to link that investigation to the mad march of humanity towards extinction.

The main character in this book shares your name. Is he similar to you in other ways as well?

The main character in this book shares your name. Is he similar to you in other ways as well?

I took the risk of grafting onto the chronology of my real life a fictitious story, because it was the best conduit for the story. The character "Ariel" has my name, my family, many of my historical experiences, some personality traits. But he is as invented as everybody else in the novel, and was constantly astounding me. There are things he does that I have never done and never will.

What was most challenging thing about melding aspects of truth and fiction? How did you determine the right balance?

There was no balancing. It was essential that the reader always be caught, precisely, off balance, not knowing what is historical and what has been imagined. This is related to the main theme of the book: how the past is constantly reinvented so that many versions of something can be simultaneously true (the death of Allende or the narrator's past or the story of a wedding photographer who can tell the future of the couples he is taking pictures of). It makes the novel playful and enjoyable, despite touching upon serious themes (murder, military coups, climate apocalypse).

In the novel, Dorfman is a writer hired by billionaire Joseph Hortha to investigate the death of Allende. What is your personal connection to these historical events?

I was working for Allende at the moment of the coup. I should have been in the Presidential Palace that day. But I was saved by a series of extraordinary coincidences. I use the survivor's guilt the real me felt (somebody died instead of me) to motivate the narrator's search for the truth. It is his way of going back to the scene of the crime, perhaps redeem himself.

There is always a degree of tension between Dorfman and Hortha. How does their relationship help drive the story? Is there real-life inspiration for this character?

That tension was indispensable so that they could evolve, go through ups and downs as they grow closer together when a final terrible revelation makes Hortha vulnerable and in need of comfort and help. As to Hortha, who is to say he does not exist in real life?

The book's central question revolves around whether Allende committed suicide or was murdered. What does Dorfman's ultimate discovery reveal about his humanity, and ours collectively?

I would be betraying one of the elementary rules of writing if I were to reveal the ending of a mystery novel. The last chapters are full of twists and turns, and readers will have to decide for themselves what happened to Allende during his last minutes on this Earth. How my alter ego deals with the message Allende seems to be sending is a way of testing him and could well provide a model for how the collective we of humanity might think and love our way out of the perilous present into a different, more compassionate world.

Dorfman's attention is torn between the mystery and his own past. What bigger message did you hope to communicate about loyalty and the way past trauma shapes our lives?

I really don't have a bigger message. I don't want to impose my views on readers. I'd like them to emerge trembling from the vortex of my writing, ready to confront their own traumas with the same naked sincerity my characters have achieved as they dance on the brink of salvation and death.

You have written prolifically throughout your career. What has been most rewarding about your success, and what would you say to writers who are struggling?

I have been a chameleon-like author, taking on every conceivable genre: memoirs, poems, short fiction, children's stories, journalism, literary and political essays, op eds, operas, plays, screenplays, even a musical and, of course, novels. But even in novels, I never repeat myself.

My first one, Hard Rain, is made out of book reviews of nonexistent novels from the Chilean revolution. My second, Widows, pits an old peasant woman against an army captain, as she claims bodies that appear in a turbulent river as those of her missing men (but I set it in Greece, narrated by a Danish author who was "disappeared" by the Nazis). Then comes The Last Song of Manuel Sendero, where a group of pesky fetuses stage a strike and refuse to be born until adults make the world a worthy place for them. Next, Mascara tells the story a man with no face who, through his invisibility, can enter any domain and ferret out, with his camera, all the crimes of a corrupt city.

And so it goes: Konfidenz is a spy story that transpires in Paris; The Nanny and the Iceberg is a satirical detective story where Che Guevara plays a central role; Darwin's Ghosts is, appropriately, a ghost story about an adolescent whose face has been taken over by an indigenous stranger whose intentions are not clear; Cautivos is a historical novel set in the Sevilla jail where Cervantes is having trouble beginning Don Quixote; and The Compensation Bureau is a sci-fi saga told by a Guardian Angel concerned about humanity's lethal fate.

What better reward than to have conceived all these universes, tried out all these styles? And that's my advice to struggling writers: struggle on. If success comes, welcome it, but do not become a slave to what others think of you. Write your heart out. Oh yes, and be ruthless.

What's next for you? Are you working on anything new right now?

I'm exhausted by The Suicide Museum, but there are a number of short stories I have postponed that await my attention. Other Press will be publishing Allegro next year, a novel narrated by Mozart as he tries to unravel the mysteries behind the deaths of Bach and Handel. --Angela Lutz, freelance reviewer