_hugh_chaloner.jpeg)

|

|

| (photo: Hugh Chaloner) | |

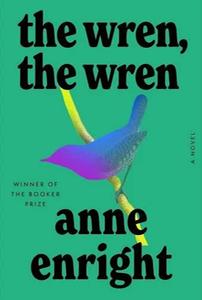

Anne Enright is the author of eight novels, two short story collections, and a memoir of motherhood. She was the first Laureate for Irish Fiction (2015–2018), and won the Man Booker Prize for The Gathering in 2007. She is also a professor of creative writing at University College Dublin. The Wren, the Wren (reviewed in this issue), a novel about the generations descended from Irish poet Phil McDaragh, bears her hallmark themes of family legacy and creativity.

We're seeing a real flourishing of Irish writing--this year's Booker Prize longlist, 'the Sally Rooney effect.' Do you see Irish writers as a sort of literary vanguard? Or has it ever been thus, and the world only realizes it occasionally?

The world realizes how flourishing the Irish literary scene is about every five minutes, and it's like no one can figure it out--is it something in the water? A culture is like an ecosystem; it is hard to say what one factor makes it work so well. When I came of age, earnings from fiction were completely tax-free, so that was certainly encouraging. But actually, if you are a smart young person in Ireland, you see people winning prizes and whatever else gets the press excited, and you think quietly to yourself, "Someday, that is going to be me." Then, in your early 20s, you walk into a launch in a bookshop in Dublin, and the writers are not just on the shelves, they are in the room. It is profoundly exciting. It is a fun place to be.

Did you have particular poets in mind as you were crafting Phil McDaragh's verse? (Seamus Heaney? Michael Longley?)

Phil is 15 years older than Heaney or Longley, and he wrote before the amazing flowering of Northern Irish poets that happened in the 1970s. So, no, not those two--and besides, I would not dare! Though a lesser talent, Phil had some of the same influences as they did: medieval Irish verse is important to him, as are Paddy Kavanagh, Austin Clarke, and Padraic Colum. Michael Hartnett is in there, especially his translations from the Irish, and I used a sprinkling of Louis MacNeice in satirical mode. Phil shares my love of John Donne, which would be unusual perhaps for an Irish lyric poet. He is, however, completely himself. I found him very easy to access as a character, but his poetry was amazingly hard to write (I suspect he found it difficult, too).

Carmel thinks of Phil: "He had a self-important heart. Confidence? Was that all it took? Surely here was some extra stupidity required." Is the narcissistic artist a specifically male type? (cf. Monsters by Claire Dederer).

Some artists are lovely, modest people--warm, empathetic, good to their mothers, nice to their children--and some are monsters. What they all share is a sense that their work is necessary: it is something they need to do, and they think other people might want to see it. For someone like Carmel, that's a fairly astonishing claim to make on the world's attention. You can call it narcissism if you like; she certainly would.

But here's my theory about all that: a person's narcissism expands to fill the available space. We let men get away with being monstrous, in ways that are quashed in women from their earliest days. Sometimes, we expect male monstrousness: we admire and reward it. So I would not gender either art or monstrousness--society plays a role, too.

I found Nell an utterly convincing mouthpiece for the preoccupations, wit, and ennui of today's young people. How did you go about tapping into a modern sensibility to create her voice?

I found Nell an utterly convincing mouthpiece for the preoccupations, wit, and ennui of today's young people. How did you go about tapping into a modern sensibility to create her voice?

I suppose I went online. I teach and I have children, so young people are not a mystery to me. But actually, the secret answer is that I went back to my own early work. I tapped into the modernist sensibility at play in my first short stories, which I wrote in my 20s. Nell's interaction with her period app, for example, is very close to work I did about women and modernity, women and television, women and machines.

There's a striking moment when Nell is at the top of the Utrecht cathedral tower and is overtaken by a conjunction of beauty and fear that she identifies as awe. Is this a depiction of Stendhal syndrome? What did you intend with this scene?

I had to look this up! Stendhal syndrome is a kind of panic attack suffered in the presence of great art. It reminds me of the ecstatic response some Romantic artists had to landscape. Way back in 1757, the Irish philosopher Edmund Burke talked about the sublime as having the power to compel and destroy us--beauty is calming, but the sublime is agitating. Nell is not a religious person (she does not belong to any tradition), but she is interested in the existence of what she calls a higher form of consciousness. Going up the spiral staircase of the church tower, she suffers a mixture of claustrophobia and vertigo, and she has a panic attack that ends with a feeling of revelation. Nell discovers the sublime. I don't want to be too literal, but this mixture of ecstasy and fear is a tiny bit like the feeling she had in bed with her abusive lover, Felim. So the experience of the tower releases her from that dependency, somehow.

The McDaragh family seems to be caught in cycles of damage. I wondered if there might also be an environmental parable in their psychology: greed and self-importance versus love and dependence. How do we get trapped in these patterns?

I think the damage gets less with each generation, so it's not a cycle, it's a kind of spiraling outwards towards better, easier times. The first rupture is the loss of Carmel's father, Phil; that is the trauma that takes time to heal. I am not sure there is a parable there about dependence. Carmel and Nell love each other absolutely, as Nell says, but that doesn't make for happiness, at least not in the short term. I was about to protest that I don't write parables, but then realized how much I was influenced by the story of Martha and Mary in the New Testament. Carmel gets to tend and fret--she is the Martha generation. On either side, her father and her daughter have adventures: they get to believe, imagine, be passionate; they have the luxury of making mistakes, they allow themselves to blunder around. --Rebecca Foster, freelance reviewer, proofreader and blogger at Bookish Beck