|

|

| Vashti Harrison | |

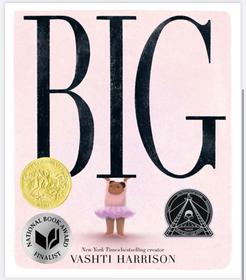

Vashti Harrison recently became the first Black woman to win the Randolph Caldecott Medal, given for "the most distinguished American picture book for children," for her 2023 book, Big (Little, Brown). Harrison also received two Coretta Scott King honors, in the Illustrator and Author categories.

Big has had a wonderful year. First, it was a finalist for the National Book Award and now it's received the Caldecott Medal as well as two CSK honors. What are you thinking right now?

It's more than I could ever have imagined. The National Book Award was so unexpected and such a wild journey with many authors and illustrators I admire! For the Coretta Scott King committee to give me two honors is incredible--particularly for the writing honor. I feel comfortable with the title of illustrator, but author will always sound foreign. To be recognized for the text in this book is truly humbling.

And the Caldecott? I wished, I hoped for an honor. Never, ever did I believe it was possible to win the Medal. I watched the livestream just to make sure I didn't dream it all up!

Would you describe Big to our readers?

Would you describe Big to our readers?

Big is the story of a young girl who's experiencing some really BIG feelings, particularly about her body. It traces how the meaning of the word big can change in a girl's life: when you're young, big can be a word of affirmation. But as a girl grows older, it can become something negative. The book tracks how this young girl internalizes some of that negativity, and follows her on her journey to self-love. In the end she reclaims big as just one of the words that define her. I hope the book encourages young readers to know they get to define who they are--no one else gets to decide that for you.

What inspired you to create Big?

Part of this story is inspired by my own childhood and relationship with my body. I started writing it to process many of the experiences and unresolved feelings I still carry. It's an ongoing journey, but I wanted to expand the narrative beyond myself, to create a roadmap for young readers on their own journeys toward self-love. I wanted to make a book about Black girlhood, touching on things that many young Black girls experience in the United States, particularly anti-fat bias and adultification bias.

The illustrations are brilliantly effective: the color palette, the formatting, the use of double-page spreads, that gatefold (!). Did this story come to you fully formed? Or did words or images come to you first?

The images definitely came first. The first thing I drew was a sketch of the lowest point of the book: the girl curled up, back to the viewer, boxed in. No words. Just isolation. I wanted to tell the story of how this girl got here, and how she breaks free. In the beginning I hoped to make a fully wordless book, but there was so much more to say.

The ah-ha moments for me were realizing I could use the gutter and trim size of the book to help support the narrative. That led to me realizing that this is a book about words--I can have the girl literally hold words and hand them back to people. Still, the text is quite spare, so I used color to help communicate her emotions and feelings.

How did you find such an excellent balance of text and illustration?

I went back and forth on edits with my incredible editor and friend Farrin Jacobs. This book only has about 150 words and each one is like a number in a sudoku puzzle. If we put one in, we'd have to take another out. She guided me through this process, especially when I started questioning everything or felt too close to the subject matter.

Have you had the chance to read this book with children?

I've had the opportunity to do school visits across the country, and it's always so amazing to hear how thoughtful and empathetic children are and how they have such a strong sense of justice. The responses have been great. I've seen some amazing classroom projects where they've made posters listing all the positive words that describe themselves, and notes about what to do when they see someone is struggling or being bullied.

What were you hoping to accomplish when writing and illustrating this book?

As much as I hoped this story would be a mirror for young Black girls and a window into this type of experience, I also wanted it to act as an appeal to adults to consider the words we use with and say to children. You never know what's going to stick with a kid. I remember all too well what it was to be that girl, so I want to create space for kids to just be kids, to let their bodies change and grow without adult appraisal or criticism.

Your first book, Little Leaders: Bold Women in Black History, was published in 2017 and you have been rather prolific since then. What have the past seven years been like in publishing?

SEVEN YEARS! I can't believe it's been that long! It started like a whirlwind with Little Leaders, Little Dreamers, and Little Legends. I said yes to so many projects in such a short amount of time: I illustrated four books in 2018 and three came out in 2019. When the pandemic hit and all my events were cancelled, it was really my first moment to slow down. That's when I started doodling my initial thoughts about Big. Those years all blend in my mind, but I think it's been a great seven years for kid lit. My friend, author and editor Winsome Bingham, believes we're in another golden age of picture books. I tend to agree, and am grateful to be able to witness so many diverse, creative, and beautiful books being published. --Siân Gaetano, children's and YA editor, Shelf Awareness