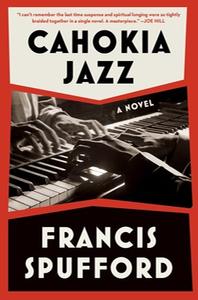

Turning facts into fiction has gained British author Francis Spufford enviable international awards and praise. In his brilliantly immersive third novel, Cahokia Jazz (Scribner, $28, reviewed in this issue), he presents an alternate U.S. history spotlighting a predominantly Indigenous Midwest metropolis in 1922 fighting for its continued existence.

Turning facts into fiction has gained British author Francis Spufford enviable international awards and praise. In his brilliantly immersive third novel, Cahokia Jazz (Scribner, $28, reviewed in this issue), he presents an alternate U.S. history spotlighting a predominantly Indigenous Midwest metropolis in 1922 fighting for its continued existence.

You began your authorly career focusing on nonfiction, then switched to writing novels in 2016. What prompted the change?

I'd always been a nonfiction writer of a very narrative kind, stealing techniques from novels wherever I could. A point came when I realized I wanted the rest of what fiction can do, and that it was only a kind of cowardice holding me back. But there was some loss as well as gain in making the changeover. There are ways that nonfiction can take a grip on the real, and fascinating, and stubborn, and contradictory world that fiction can't. I stand by my earlier enthusiasm for nonfiction as a form, even if I've moved off to do something else.

Your three novels thus far each combine real events/places with stories you create: mid-18th-century Manhattan in Golden Hill, the 1944 New Cross attack in London in Light Perpetual, and now Cahokia Jazz. What inspires you to rewrite history this way?

I think it's because, thanks to the path I followed to get to the novel, I'm now a writer of fiction who tends to find the starting point for their imagination in a factual thing. An unexpected historical event, or a place--very often a place, I'm a place-driven guy--but at any rate something granular, gritty, for me to grind away at. But what I want to do now is to explore them in story. Why history? Probably this has something to do with coming from a family of historians. Both my parents were history professors, professionally and imaginatively concerned with medieval money (my father) and 17th-century village life (my mother). The past was always... present. You could see me as the black sheep of the family--the one who took the family business in an irresponsible direction, by making things up.

Cahokia Jazz is your second novel set Stateside, this time centering an Indigenous community. Were you, as a white British writer, ever concerned about potential comments/criticisms citing cultural appropriation?

Cahokia Jazz is your second novel set Stateside, this time centering an Indigenous community. Were you, as a white British writer, ever concerned about potential comments/criticisms citing cultural appropriation?

It seems to me fundamental to what fiction is that writers should write about what they haven't personally experienced. That's non-negotiable. But it doesn't cover the issue of power involved, and of who gets to represent, and who gets to be represented. I did, very much, worry when writing Cahokia Jazz, not so much about accusations of cultural appropriation as about the thing itself. In the end, my sense that it was okay to go ahead rested on two things.

One, that the Indigenous people in the book do not correspond to any existing Native American nation or people. They are a projection of what might have been, had the situation witnessed by [Spanish conquistador Hernando] De Soto on the Mississippi in the 1540s continued: the large towns populated by maize farmers, busy working out the next evolution of the Mississippian cultural complex. In our world, all that got destroyed by disease. In the book, it's continued, changing for five more centuries and fusing itself with a mass of outside influences, especially including a weird Catholicism. So it's not that I am speaking for a culture that ought to be speaking for itself. I'm conjecturing a culture that never existed. I hope that means I'm not pushing aside anyone else from the microphone.

Then, two, I'm an outsider. I'm not a Native American, or an African American, but I'm not a white American, either. It's all foreign to me. I think there's a freedom in that, to speak from somewhere off the usual map. I hope I make good use of that freedom in the book. That's what will justify it, or not.

The breadth of research required to create Jazz is astounding. How did you choose the "real" elements of your fiction? How did you conduct the research?

I love the process of research, so it's a treat for me, not a burden. In fact, I often have to tear myself away from the pleasures of finding-out, to make myself do the work of writing-down. But having said that, I'm not a historian. (Sorry, parents.) My task is never to find out everything that can be known about a subject, only to find out enough about it to tell the story. Only to find the right details to make an imagined world solid. It's an art of illusion. You develop an eye for what will work, an ability to swoop quickly on the promising single data-point from which the illusion can be woven. It's less laborious than you'd think. I'm a crow looking for shiny things, not a patient reconstructor.

Your ending "Notes and Acknowledgments" was such an entertainingly illuminating gift after an already spectacular read. This, especially: "what makes this altered America in this 1922 different is that, in this timeline, it was the variola minor or Alastrim form of smallpox that came out of West Africa first, and was carried across the Atlantic in the 'Columbian exchange.' " A single, microscopic germ with a 1% death rate could have changed all of history. How did you discover such a minuscule fact?

Minuscule, but with huge implications. Honestly, this stuff is there in plain sight. Charles Mann's 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created has got a good discussion of the disease history to start off with, and then if you want to dig deeper there's Ann Ramenofsky's Vectors of Death: The Archaeology of European Contact.

On a wider subject--I really like using a "Note" or another bit of a book's apparatus, apparently outside the story, to add a sly extra element to the story itself. (Probably the result of reading Nabokov's Pale Fire at an impressionable age.) Anyone who ends Cahokia Jazz itself feeling sad should check out the record recommendations at the end of the Note for some in-world consolation.

Your opening dedication to Professor Kroeber's late celebrated, iconic daughter... I shouldn't give away her identity here. You mention, "She wouldn't necessarily approve of the foundation on which this particular ambiguous utopia stands." Did you know/meet her before she passed? What do you think her reaction might have been to your characterization of her father? Any guesses as to what she might have thought of your book?

I never met the icon in question, to my sorrow. She was due to come to a panel discussion on utopias in London that I was also involved in, but this was towards the end of her life, and she decided against the long flight. But her work has been a familiar and wonderful presence in my life ever since I was a child reading--oh, this is ridiculous--The Wizard of Earthsea, and it's Ursula Le Guin we're talking about. Obviously!

I'd hope that she'd enjoy Cahokia Jazz as a piece of making and imagining: she was a person with a large and eclectic capacity for taking pleasure in verbal artistry, and a lot of what I'm doing with the city of Cahokia in the book is strongly influenced by her way of creating the imaginary gardens in which real toads, and stories that matter, can be found. Where I think she'd dissent, maybe, is from my sense that the heavily qualified good place (eu-topos) that my Cahokia is can come about because a price is being paid for it in innocent blood. She was interested in utopias, politically and as a literary form, but her great thought experiment of a story, "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas," shows her refusing the idea that utopia can ever be acceptably paid for in suffering. I mostly agree with her. I certainly detest the ways in which our good life in the rich world now is paid for by misery elsewhere. But I have a sense, probably ultimately a religious one, that just sometimes, when the sacrifice is voluntary, blood may be the needful thing to make our walls stand.

As for the picture of her father: oh, I hope she'd like it. I took it as far as I could from her mother's memoir of him, and from her own short story, "Imaginary Countries," where her memories of her 1930s childhood summers in Napa Valley have been relocated to imaginary Eastern Europe, and there's the tenderest portrait of happy small girl and older academic father. He was clearly much loved.

Your books are bestsellers on both sides of the Atlantic. Would you say your audiences' reactions differ significantly by geography?

Maybe in this respect: when I'm writing about America, in Golden Hill and now in Cahokia Jazz, my British readers tend to respond as if what's happening is some enjoyable tropes being laid out. The tropes of 18th-century lit, before, and now the tropes of the 1920s crime novel. Men in hats and femmes fatales. But for Americans, the test is whether my stuff is recognizable. Whether, in its weird and oblique and history-twisting way, you can read my books and say: yeah, this isn't what I was expecting, but this is us. This is recognizably about the real place we live, even though it's written from the peanut gallery where the rest of the world gazes at America, and wonders about it, and worries about it. I hope Cahokia Jazz passes that test.

Your groupies must know: what might we expect next?

A fantasy novel set during the London Blitz--which, for the first time ever in my fiction, looks as if it's going to need a sequel. --Terry Hong