|

|

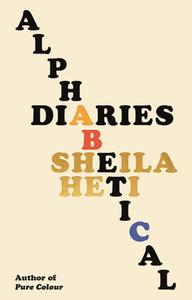

| Sheila Heti (photo: Sylvia Plachy) |

|

Sheila Heti is the bestselling and award-winning author of 11 books, including the novels Pure Color; Motherhood; and How Should a Person Be? She lives in Toronto, Canada. After being excerpted over 10 weeks in a New York Times newsletter in 2022, her memoir Alphabetical Diaries (reviewed in this issue) was published this month by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Here Heti discusses her process for this project, its incubation and many iterations, and her trepidation about putting her diaries out there for a larger audience.

What instigated your return to your diaries for this book, and how did the concept of alphabetizing their sentences come to you?

I don't remember how the idea came to me, but I really like spreadsheets, and thinking in the form of spreadsheets, so it didn't seem so out of place to put my diary into Excel and alphabetize it. I began the project in 2010, when I had just finished writing How Should a Person Be? and I think one of the motivations was that I wanted to see who I had really been the past six or seven years, in contrast to the self that I had fictionalised. It's very easy to mistake a fictionalised self--the self you've turned into fiction--with your real self, and I wanted to remind myself of the difference, so looking at my diaries seemed like a good start.

What has been your relationship to diary writing outside of this project?

I have kept diaries on and off since I was a child. I learned early on that I was not the sort of person who could keep up a daily diary; it's just something I do when I feel like it, often when I'm going through something difficult emotionally. I write my diary on my computer. Sometimes I'll go six months without writing in it. I don't think I write very differently in my diary from how I write in other places. There maybe is a kind of seamlessness to diary writing and fiction writing, in the rhythm of the sentences, the sorts of things I notice, what seems interesting to think about.

Were there any patterns or repetitions that emerged from this project and were particularly surprising, disappointing, curious, or intriguing to you?

I don't think I had any strong expectations going in, so I wasn't experiencing surprise, disappointment, etc. as I was editing. I suppose what made the biggest impression on me was how few themes actually interest me, or perplex me, or beg to be written down. Romantic relationships, writing, money, what city I should live in--so many sentences came back to these five themes. I would have imagined there would be more variety.

What was the editorial process like for this project?

What was the editorial process like for this project?

It took 14 years to edit, so it's hard to summarize. I was forever reverting to earlier versions, realising that I had made mistakes in my editing, cutting the wrong things. It took a long time for me to figure out what a book like this should consist of: how long it should be, whether the sentences should each be on their own line or in a continuous paragraph; what to do about the names of the people in my life. I had to make my life, in some ways, smaller than it had been, in order for the reader to feel continuity throughout the book, and I had to merge many people into single characters, in order for there to be something like "characters" in the book. It was a lot of thinking, figuring out--none of it came naturally. I had never written without chronology before. Rhythm becomes important, alternating colours and feelings, sentences pressing up against sentences to give a sense of vibration--the placement of sentences in relation to other sentences; I never thought I'd figure it out.

How do you think of this project in the context of your printed pieces?

It seems most like my first novel, Ticknor, which is the inner monologue of an anxious man on his way to a dinner party. That book and this one both focus on the minutiae of life, and the smallness and pettiness of one's own thoughts, especially one's own thoughts about oneself. In both books, you never get very far outside the narrator.

At this point, Alphabetical Diaries has existed in quite a few forms: as a series of your own diaries, as an N+1 essay, as a newsletter from the New York Times, as a book. Can you reflect a bit on what differences you think these various forms make?

I think this final book form is always what I was aiming for, it just took me a long time to get here. The newsletter was nice because it was a short little bite of the book, easy to take in. But I always wanted it to have an endless feel, too, the way life and the self feel sort of endless, so that form wasn't quite right. But I remember that when I published them in the Times, I still wasn't sure I wanted to publish it as a book, if I wanted to be that public with this project, if it could resolve into a book, so it seemed to me like that might be the final iteration of the project. I say this, even as I remember hoping that it could find its way to being a book.

What has the process been like of having people read your diaries?

I was only terrified the week it was going to appear in the New York Times, because a newspaper is so public, and it's not really the place for art, but for news and journalism. I thought people were going to wonder what this project was doing there, amidst writing about war and economics and social issues. I didn't know they were going to format it in such a way that it was going to look like something very different from a newspaper column or article; I had no idea how it was going to be presented. So in advance of that, I was very scared. But people seemed to like it--at least the ones who got in touch with me--and I think publishing it in the Times sort of inoculated me against feeling fear about publishing it as a book, and I'm actually looking forward to it being in the world. It's not really a diary anymore, now that it's in this highly edited, highly formal state. I don't think it reads like something that should be kept private. I think it now feels more like a novel, a character, a world. --Alice Martin, freelance writer and editor