|

|

| photo: Laura Bianchi | |

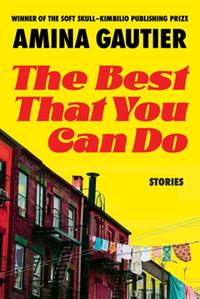

Amina Gautier is the author of three award-winning short story collections: At-Risk, Now We Will Be Happy, and The Loss of All Lost Things. Gautier has published more than 150 short stories and has received the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in the Short Story. She holds a Ph.D. in English Literature and is a native of New York City. The Best that You Can Do (Soft Skull Press) is a collection of very short fiction.

Handsell readers your book in 25 words or less:

A collection of very short stories that elaborate on the realities of a diasporic existence, split identities, and the beautiful potency of meaningful connections.

On your nightstand now:

The nightstand is pretty stacked. On it I've got A. Van Jordan's poetry collection When I Waked, I Cried to Dream Again; [Theodore] Ted Wheeler's historical novel The War Begins in Paris; Susan Muaddi Darraj's short story collection Behind You Is the Sea; Dionne Irving's short story collection, The Islands, and her novel, Quint; Katherine Vaz's novel Above the Salt; Jhumpa Lahiri's Roman Stories; and Gioia Diliberto's historical novel Coco at the Ritz. For rereading, I have Marc Fitten's novel Valeria's Last Stand; Michael Cunningham's The Hours; Colson Whitehead's Underground Railroad; Nella Larsen's novels, Quicksand and Passing; and Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

Favorite book when you were a child:

Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird. I first read it during the summer between my fifth- and sixth-grade years and then I read it again in ninth grade. I was a total tomboy, a real rough-and-tumble kid, and I was fortunate enough to be raised alongside a male cousin, who became a surrogate older brother for me. I followed him around, lived in his shadow, and always wanted to do everything he did--wrestle, karate-chop, light fireworks--and I have all the scars to prove it. When I read To Kill a Mockingbird, I loved the sibling dynamic between Scout and her older brother, Jem, and I saw similarities between the scrappy, intelligent, inquisitive Scout and myself.

Your top five authors:

I love the language and imagery of Stuart Dybek; the subtlety and restraint of Kazuo Ishiguro; the linguistic mastery and unapologetic bluntness of Jamaica Kincaid; the imagery, style, and structural maneuvers of Jhumpa Lahiri; and the satire, intelligence, and wit of Percival Everett.

Book you've faked reading:

Oh, I never ever fake it.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

John Gardner's The Art of Fiction.

Book you've bought for the cover:

I never judge books by their covers.

Book you hid from your parents:

Why would I ever hide a book?

Book that changed your life:

This one is a two-fer. Reading Charles Chesnutt's The House Behind the Cedars while an undergraduate at Stanford University inspired me to pursue graduate studies, obtain a Ph.D., and become a literature professor whose research is grounded in 19th-century American literature. Reading Alice Walker's The Color Purple helped change my personal, rather than professional, life. At the time of my reading the novel, I was still figuring out my spiritual beliefs, and I found myself encountering a lot of religious hypocrites whose behavior left much to be desired. Reading Walker's novel--especially the part where Celie and Shug, two women who have had religion weaponized against them, have a debate about religion that transforms into a conversation about love, joy, and giving the best of oneself as a form of worship--cut through the noise of the hypocrisy and helped shape my thinking about such matters in new and innovative ways.

Favorite line from a book:

Another two-fer. My favorite line from any book comes from John Gardner's The Art of Fiction: "To write with taste, in the highest sense, is to write with the assumption that one out of a hundred people who read one's work may be dying, or have some loved one dying; to write so that no one commits suicide, no one despairs; to write, as Shakespeare wrote, so that people understand, sympathize, see the universality of pain, and feel strengthened, if not directly encouraged to live on." A close second comes from one of Celie and Shug Avery's conversations in The Color Purple when Shug says, "I think it pisses God off if you walk by the color purple in a field somewhere and don't notice it."

Five books you'll never part with:

Kazuo Ishiguro's The Remains of the Day, Charles Johnson's Middle Passage, A. Van Jordan's M-A-C-N-O-L-I-A, Jhumpa Lahiri's Interpreter of Maladies, and Toni Morrison's Beloved.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Louisa May Alcott's Little Women. I was a great fan of Jo March, another tomboy who was tough, loving, and smart and who didn't conform to societal expectations, even when times were rough or financially challenging (and who wanted to be a writer!). I enjoyed her friendship with Laurie--and then I got to the part where Jo's sister Amy marries Laurie. I got so angry I threw the book across the room and never finished it. I didn't necessarily want Jo and Laurie to be together if they were just friends, but it seemed icky for Laurie to get with her sister afterwards. I was definitely too young when I read it, because I still liked those nice convenient endings where characters did what they ought to and everything worked out well with a silver bow. I hadn't learned yet to read as a writer. I've since reread or finished reading numerous books that upset me or which I didn't care for or understand upon first read, but Little Women is one I've never been able to return to. I'd like to revisit it with mature eyes.

Favorite short stories when you were a child:

I loved Toni Cade Bambara's "Gorilla, My Love"; Katherine Mansfield's "Bliss"; Stanley Elkin's "A Poetics for Bullies"; and Philip Roth's "The Conversion of the Jews," all of which I read between sixth and eighth grades. From fourth through sixth grade, the short stories I'd been assigned to read were of this ilk: O. Henry's "The Gift of the Magi"; Edgar Allan Poe's "The Masque of the Red Death"; Nathaniel Hawthorne's "Young Goodman Brown" and "The Birth-Mark."

They are stories with ethereal qualities where much depends upon coincidence. They weren't doing it for me. I found what I was looking for when I got assigned the Bambara and the Elkin stories, with their sassy and young narrator-protagonists who hide behind their bravado to conceal their own sensitivity and their difficulties navigating the perplexities of an adult world in which they find themselves prematurely thrust and whose rules are constantly changing.

Then you have the Mansfield and the Roth, which don't rely as much on voice and use close third-person points of view but allow their reader deep dives into the minds of their protagonists at moments where their beliefs and expectations are upended. The Mansfield story has that poignant moment with Bertha Young and the pear tree, and the Roth story has that hilarious moment where all the boys encourage Ozzie to jump because they've misheard the word martyr as Martin--that never fails to crack me up. Those four stories have remained close to my heart for some 35 years now.