|

|

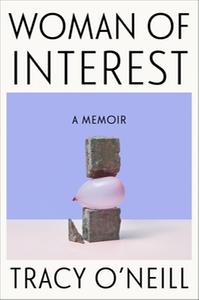

| Tracy O'Neill (photo: Oskar Miarka) |

|

Tracy O'Neill's memoir, Woman of Interest (HarperOne, $28.99; reviewed in this issue), recounts her search for her biological mother in 2020-21, which involved investigative research and a trip to South Korea. Her previous books are the novels The Hopeful and Quotients. In 2015, O'Neill was a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree. She is an assistant professor of English at Vassar College.

In November 2020, you contacted a private investigator to help you find your biological mother--but you ended up not hiring him and doing much of the legwork. Did it seem like you had temporarily become a PI yourself?

Joe, the private investigator, became something like my private investigation sensei. During those couple of years, I did become an investigator of sorts, as you say, absolutely. Many of us become investigators of ourselves and those who we take to be of interest to varying degrees. I think this is beautiful and optimistic.

You ran into a number of problems, including the unreliability of documentation related to your adoption (even basic information like the spelling of your birth mother's name). How did this affect your confidence in your origin story and in written history in general?

Throughout the search, I vacillated in my degree of confidence in details. But also, I am just generally someone who takes history to be constructed, riddled with mistakes, and interpreted. Like many academic types, I'm looking at what's useful and where the logic hiccups when I look at documents. To be a disgusting pig vis-à-vis cliché, I also seem to be thinking about the sausage-making of narratives.

The language gap was another persistent issue when communicating about and with your family in South Korea. What did you feel about how technology (and relatives or strangers with agendas) translated sensitive interactions such as your first conversations with your biological mother?

I'm so sensitive to language--when the language is English. But in Korea, it was as though I'd lost a whole sense. I often wondered if Google Translate or Naver Papago, the other translation app used, caught the connotation someone intended. In other moments, however, it was as though the language apps said something more plainly and clearly than perhaps even the speaker intended. Something true of what they seemed to feel was conveyed, even if they hadn't quite meant to so baldly reveal themselves, such as when (late in the book) my mother speaks of her "mother's wish" [to see her daughter married].

This whole quest happened at the height of the pandemic. How did Covid circumscribe how you went about things? Can you see any way in which those limitations may actually have been beneficial?

This whole quest happened at the height of the pandemic. How did Covid circumscribe how you went about things? Can you see any way in which those limitations may actually have been beneficial?

A lot of the "official" or "legitimate" ways of searching were unavailable to me. I also had a considerable amount of time to obsess without distraction. In this way, I was perhaps more pushed to seek answers myself, and therefore to have more conversations with people. I also might have treated that period of my life as a season of more gradual change than a come-to-Jesus moment.

Toward the end there's a sense of letdown when you don't experience instant emotional connection with your newfound family. What made you decide to turn this disappointment into a key element of the book rather than just think, "Oh well, there's no good story here"?

To me, the subversion of expectations often is exactly what makes for a good story. Paradoxically, as a reader, I don't necessarily want to get what I hope for. So I didn't really worry about that.

Your relationship with your Serbian boyfriend, N, deteriorates almost in parallel to the investigation. How do you see this as reflecting on the main plot?

This is a book that explores a time in my life in which I was searching for a sense of home and wondering who that included. As it turned out, neither N nor Cho Kyu Yeon were people with whom I could make a home. Sometimes, you take a chance on a boyfriend or a mother or a stray dog. You don't want your life to be small and controlled. You realize something of your life has become a locked and padded room. You take a leap of faith in other people and also in yourself, that you can go on, you will go on, and in moments those leaps are irrational, and maybe a little sad, but still provocatively alive.

In terms of genre considerations, how was this narrative shaped and how did you push against the conventions of memoir?

I knew that my own experience gathered the story, so I felt very free to take liberties with forms and genre. There's obviously a procedural plotting that strings the narrative together, but in moments there are other weird impulses that I followed. The final chapter moves between something like an essay and a frame narrative and poem. This is a work of memory, like all memoirs, but it was important to me that I did not end the book in a way that suggested that the logical end of memory is an ossified conclusion. I wasn't going to do false consolation or unearned redemption.

The book is also quite dialogue-heavy in many sections, which is common in detective fiction and noir. I thought about how Cho Kyu Yeon was something like a femme fatale, but also a missing person, but also an outlaw woman. I thought about how the person I could be felt like a missing person in a terrible couple of years for people collectively. I wanted to mobilize the figure of the detective in thinking about how we look for the clues to ourselves when we're lost and desperately wish to "solve" ourselves.

Do you have any enduring bond with Cho Kyu Yeon and/or the siblings and cousins you met on your trip?

Perhaps the book is an enduring bond of sorts. We haven't spoken since August 2023. --Rebecca Foster