Poet and author Hettie Jones, who with her husband, LeRoi Jones (who later became the poet and playwright Amiri Baraka), "made her household a hub for Beat writers and other artists--but who was often described as a footnote in the rise of her famous spouse as 'the white wife' he disavowed,' " died August 13 at age 90, the New York Times reported. The author of 20 books, many of them works for children and young adults that focused on Black and Native American themes, her works include Big Star Fallin' Mama: Five Women in Black Music (1974); poetry collections Drive (1997), All Told (2003), and Doing 70 (2007). She also co-authored No Woman No Cry: My Life with Bob Marley, a memoir of Rita Marley, widow of Bob Marley.

Poet and author Hettie Jones, who with her husband, LeRoi Jones (who later became the poet and playwright Amiri Baraka), "made her household a hub for Beat writers and other artists--but who was often described as a footnote in the rise of her famous spouse as 'the white wife' he disavowed,' " died August 13 at age 90, the New York Times reported. The author of 20 books, many of them works for children and young adults that focused on Black and Native American themes, her works include Big Star Fallin' Mama: Five Women in Black Music (1974); poetry collections Drive (1997), All Told (2003), and Doing 70 (2007). She also co-authored No Woman No Cry: My Life with Bob Marley, a memoir of Rita Marley, widow of Bob Marley.

After dropping out of graduate school at Columbia University to work at the Record Changer, a jazz magazine, she met the young poet LeRoi Jones and they fell in love. In 1958, they started a literary magazine called Yūgen--a Japanese word that, the table of contents noted, translated to "elegance, beauty, grace, transcendence of these things, and also nothing at all." Beat heroes like Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Diane di Prima, and Jack Kerouac were among the contributors, along with Frank O'Hara and Robert Creeley.

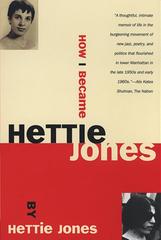

They also launched Totem Press to publish books of poetry by new writers when they were both 23. In her 1990 memoir, How I Became Hettie Jones, she wrote: "I thought there'd be no stopping us." Their apartment was a hub and sanctuary for artist friends, who often stayed with them for months at a time or gathered to help put together issues of the magazine.

In the early 1960s, however, as LeRoi Jones's fame increased and as his affairs multiplied, the marriage suffered. "He was also undergoing an ideological transition, caught up in the Black nationalist movement and its often harsh identity politics," the Times wrote. "A few months after Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965, he left Ms. Jones and their two young daughters for Harlem; he later moved to Newark, where he became Amiri Baraka, married the Black poet Sylvia Robinson and disavowed his former life."

"Hettie and LeRoi seemed to be so perfectly attuned to one another," said author Joyce Johnson, whose memoir Minor Characters (1983) includes a scene in which she and Hettie Jones came of age. "Another woman would have been bitter, but she came to an understanding of why he left. She was remarkable. The last time we spoke about it, Hettie said, 'Well, it was a necessary consolidation of identity.' She was referring not only to LeRoi's abandonment of her, but of the integrated arts scene they had been a part of, which had looked so hopeful for a time."

"Her default setting was joy," Lisa Jones Brown, her daughter, said. "She was the patron saint of lost children of all persuasions. Our favorite nickname for her was 'Mother of the Masses.' "

Hettie Jones worked as an editor at Partisan Review, and later for a several publishers. She taught writing at New York University, the New School, Hunter College, and other institutions; and ran a writing workshop at the New York State Correctional Facility for Women at Bedford Hills.

"Her poems are playful," the poet Bob Holman, founder of the Bowery Poetry Club, said in an interview. "She's not afraid of rhyme, she's not afraid of direct address--for Hettie, poetry was just another way of talking to people." How I Became Hettie Jones is available from Grove Press.