|

|

| Jacqueline Woodson (photo courtesy John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation) |

|

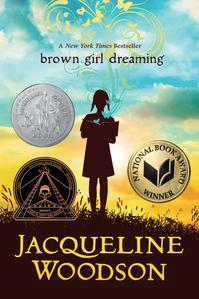

Jacqueline Woodson has always been a writer, as her memoir Brown Girl Dreaming (Nancy Paulsen, $10.99)--a National Book Award Winner, Coretta Scott King Award Winner, and Newbery Honor Book--reveals. In addition to the many awards she has garnered for her more than 40 books, Woodson was named a National Ambassador for Young People's Literature, a MacArthur Fellow, and established Baldwin for the Arts, an "Artist Residency for the Global Majority." Penguin is celebrating the Brown Girl Dreaming with a 10th anniversary event on September 21 at Symphony Space in New York City.

Here, Woodson chats with Jenny Brown, who first interviewed the author 10 years before the writing of Brown Girl Dreaming.

When you began writing Brown Girl Dreaming, had you been thinking about writing a memoir of your childhood for a while?

I started writing Brown Girl Dreaming because I wanted to figure out how I got to the place of being Jacqueline Woodson, coming from this background where my family didn't have a lot of access. I came from what was deemed by some an underserved community: a "ghetto" or what was later on called "urban" or any number of terms people use for a neighborhood that is predominantly Black and brown people and underserved. When you looked at the dynamic of it, it seemed like something that "shouldn't have happened." And here I was. I was able to publish books. I had won awards. I was able to travel because of my writing, and I wanted to go back to the beginning and understand how I got here.

There's the saying that if you know where you come from, you'll know where you're going. I deeply believe that. I wanted to get a sense of all the people I came from, the places I came from, the ideas I came from, the religions I came from.... I feel like I had always been writing Brown Girl Dreaming.

Is poetry your preferred style?

Brown Girl Dreaming is about memory. And this is the way memory comes to us. It comes to us in these small moments with this white space around it. Stuff we don't know, stuff that maybe isn't connected. One poem to the next to the next. I wanted to acknowledge that unknown. And I think if I had tried to write Brown Girl Dreaming as some kind of straight narrative, it would have been a lie. There's so much I don't remember. I also think there is something about this poetic form that allows you to slow down and really see both the words on the page and the images I'm trying to create.

So, by the time you get to the end of a poem like "I am born on a Tuesday at University Hospital/ Columbus, Ohio,/ USA--", you're in Columbus. You've seen me being born. You've seen that hospital. And then you see the cut and I open the lens a little wider, "a country caught/ between Black and White." Now you're seeing that moment in history. I wanted to make very visual but also poetic and beautiful in that way. The language was very important to me because it is also a book about language and story.

Your memoir begins by situating your birth within the historic and geographic landscape. Why did you begin it this way?

Your memoir begins by situating your birth within the historic and geographic landscape. Why did you begin it this way?

I remember sitting down to breakfast with my best friend Toshi Reagon, and saying, "I'm trying to write about my childhood and nothing happened." And she's like, "What are you talking about? When you were born, this country was on fire!" Toshi had grown up with her mom, Dr. Bernice Johnson Reagon, [who] had been through the civil rights movement. It set the narrative perspective for me: knowing that I was born within the context of time and that we all are. Inside that context was the fact that I am one generation removed--barely--from Jim Crow. All these things that were happening in our country were impacting me. That became important to me--to remember what was happening, not just to me, but to the world around me and document that.

I guess that's why the book is so challenged these days, because I document a history that speaks to a time when our country wasn't kind to Black and brown folks. I mean, there are ways in which it's still very unkind, but it was legislated unkindness happening. I wanted to write about the ways in which we were free and the ways in which we were still shackled by laws and attitudes and people's hatred. So, Brown Girl Dreaming became that story of both love and struggle and more love.

In this book, you include the universal experiences and details specific to your experience of understanding the differences between living in the South and living in the North as a young woman of color. Can you describe how you balanced these themes?

I think I balanced them the way I balance my everyday living. I think it's important to look at the struggle and the good and walk through the world knowing that we carry all of that.

When I write, a very strong theme is hope. What is the hope that keeps us turning the page; what is the hope that keeps us getting up in the morning and doing the work we were brought here to do? I think I brought that same hope to Brown Girl Dreaming, while at the same time wanting to bring truth. You can't live your life in struggle mode, and you can't not acknowledge the struggle if you want to get past it. I want all that balance to be there.

Your father's comment in "football dreams," too, points to this contrast between the North and the South. He says of the South, "...no colored Buckeye/ in his right mind/ would ever want to go there." Your narrative lays out the ways in which history and geography divide your family--was the writing of Brown Girl Dreaming a way of unifying your family?

You know, one thing that we don't get to in Brown Girl Dreaming is that when I was around 13 years old my parents got back together. And in that way, I got to really know my father, my father's side of the family and Ohio, Nelsonville, Athens, that part of the region. I do think Brown Girl Dreaming for me was about understanding that 50% of my DNA is my dad's, 50% is my mom's; and that 50/50 split is about so much more than DNA. It's about experience, it's about culture, it's about geography, and so I wanted to get that on the page.

The trauma of your brother Roman eating lead paint was a poignant moment in the book, as is your piece about people following you in the stores downtown. These scenes become momentous events for readers through their specificity. How did you decide which to include and which to leave out?

I think it comes back to me wanting to put on the page the events that really informed who I was going to become and who I was becoming. My brother's lead paint eating had an impact on me, and the wild thing of course is that history repeated itself when the lead paint crisis began in Michigan. So, there is that way in which I really wanted to show that none of this is behind us; even as we talk about it as history, there are still elements of it that are very much a part of our world today. I think that allows people to see that there is a deep connection between the past and the present. And there were things I left out that I didn't feel moved the narrative forward.

So, yeah, it's talking about me in the '60s and '70s. But it's also speaking to events that we are familiar with today, from Sandra Bland to so many people. And the same refrain is true. They're not getting followed around in stores, but even worse, they're getting killed. It's part of a continuum, a part of the work that still needs to be done. --Jennifer M. Brown