|

|

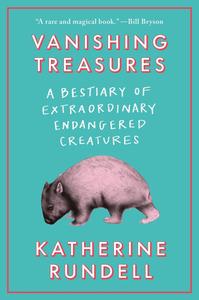

| Katherine Rundell (photo: Nina Subin) |

|

Katherine Rundell is an Oxford literary scholar and prize-winning children's author whose Impossible Creatures was named Waterstones' Book of the Year in 2023. Her fantasy works reveal the connections between the imagination and observing the natural world, something that her latest book, Vanishing Treasures: A Bestiary of Extraordinary Endangered Creatures (Doubleday; reviewed in this issue), strives to do for a whole different audience.

The relationship between fantasy worldbuilding and looking in a new way at the natural world might be unfamiliar to people. Why write a bestiary, and do you see any connection between the work you've done in Vanishing Treasures and your other writing?

What I wanted was to galvanize people's enchantment as a road to galvanizing their rage. As a way to making them angry that what we have is so far beyond our comprehension in terms not just of beauty but of complexity, and that large corporations have such disproportionate power, destroying staggering wonders of the world before we, humanity, have any chance to see or understand them in their full wonder and complexity. I was working very strongly on the idea that you cannot protect something if you don't love it, and you can't love something if you don't know it. The book is a wooing. It's a bid to ask you for your love and for your active, politically informed astonishment. If we could see our world with fresh eyes, if we could see giraffes and swifts and panthers and hedgehogs, and if we'd never heard of them, we would believe them to be mythical. You know, they are extraordinary. I wanted, I guess with kids, to help them build the instincts, and the muscle, and the understanding that is necessary for the act of wonder. That's what Impossible Creatures is trying to do, and that's what Vanishing Treasures is trying to do for two very different audiences.

Why is it important to you that we keep seeing and identifying that wonder in the natural world? Why do we as humans need this, intrinsically?

We live in a world where it is increasingly possible not to see the living things around us, not to acknowledge them, not to know them. I wanted to say: your sight, your attention, your looking is a way to be fully human, and it is also an act of duty. I wanted to ask more from people. I wanted the book to be like, look! Look at these astonishments! We have allowed ourselves too much ignorance. How do we undo ignorance learning, and how do we precipitate learning enchantment? How do you remain astonished? The answer is knowledge, the answer is learning. The answer is just never at any point allow yourself to cease to learn.

You highlight 23 extraordinary creatures in this book. How did you choose?

You highlight 23 extraordinary creatures in this book. How did you choose?

Every creature in the book had to be endangered or have a subspecies which is endangered. So, then it was a question of partly just of love. I was picking things that I thought people would adore. I wanted to pick a very careful mixture of things that you have definitely heard of and things that you may well not have. For some things it is casting light on the unfamiliar, and in some of them I'm trying to render the familiar unfamiliar.

Of all the animals you've researched here, is there one that you feel most hopeful for or, conversely, most concerned?

The ones that just happened to bend to the shape of my own love are the pangolin and the swift. The pangolin is the thing that we should all be profoundly alarmed for. It is the most trafficked animal in the world because we have a hunger for rare things. The rarer they become the greater our hunger becomes and the faster that destruction is engineered. There are very few animals in this book where I can say there is great hope. One would be the stork--their decline was staggering and precipitous, and only in the last decade have they started to sweep up again. The one where numbers drop and drop and drop, but not as precipitously as they might have, is the swift. It is also I think the one I find most staggering--the idea of a bird that can fly for a year without stopping, and eat and sleep and mate on the wing. They are just flying glory.

I'm sure this research was difficult at times, but you have also avoided a defeatist tone. How do you manage to keep hoping for a better future?

If you are moving within circles of people who welcome climate science, most of them say, well, that is not the question for us because it is too urgent to have any time for pessimism. Antonio Gramsci famously says, "I am a pessimist because of intelligence but an optimist because of will." If you were to look at the world and make an educated guess about what might happen, it would be a dark one. But it is too important for despair. I wanted the book to say--because it's true--change is possible. Radical change is possible. We have done it. We know that huge political action can be taken. Governments rarely act in moral advance of the people. What is the thing that can move a government? It's electorate.

If you had to pick one thing that everybody could wake up tomorrow and do, what would it be?

Politics. These are such huge structural problems; they need structural solutions. I know so many people who are deeply disenfranchised from politics, who feel disenchanted. But believe in politics with a small "p." Believe in group civic action--that if you join with others, change would be possible, whether finding your local political group, working part-time with a charity, or fund-raising. Protest. Protest so that you're telling yourself, at least, and those around you, that you mean what you say. And then I think meat is an easy one. It's just a habit to eat meat. It's a habit that we never had throughout history until about 50 years ago; we could just get rid of that habit quite quickly.

What do you want people to take from Vanishing Treasures?

The most realistic thing I could hope for would be that people who read it look at the world with a little more knowledge and perhaps get a little addicted to garnering of knowledge about the natural world. If I had an extravagant fairy who could grant big wishes, it would be that people might read it and be so struck by how remarkable the world around us is, how staggeringly intricate, how totally beyond our comprehension in its complexity, that they feel galvanized to shift the way they move through the world, to pay a little more attention to the ways we have allowed ourselves to make destruction a norm. If my fairy was allowing me to be really ambitious, I want members of the resistance. --Michelle Anya Anjirbag, freelance reviewer