|

|

| Adam Haslett (photo: Beowulf Sheehan) |

|

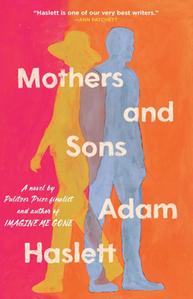

Adam Haslett is the author of Imagine Me Gone, finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award, and winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Award; You Are Not a Stranger Here, finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award; and Union Atlantic, winner of the Lambda Literary Award and shortlisted for the Commonwealth Prize. His fourth work of fiction is Mothers and Sons (Little, Brown, $29; reviewed in this issue).

Where did the idea for Mothers and Sons come from?

I had a sense of needing to write about social isolation, which so many people contend with now--more than ever in our history--and how that relates to people being overworked. The causality runs in both directions: some people avoid their isolation by overworking, some people become isolated because they're required to work too much. So I began as I almost always do, with a character looking out a window, and started asking myself questions: Who is this person? What does he do for a living? Who is his family? Despite having gone to law school, I'd never written about a lawyer before, so Peter being an attorney fell into place early. Also early on I had an intuition of his being estranged from his mother, so I started asking myself why that might be. The window he was looking out of turned out to be that of an apartment I once lived in in Lower Manhattan with a view of Trinity Church. From there, I just inched forward.

Why did you decide that Peter's perspective would be relayed in first person and his mother's perspective would be in third person?

I'm usually suspicious of first person, present tense because it's a straitjacket for the writer in terms of moving the narrative forward, but in this case it was the only tense and point of view that made sense for Peter. Precisely because he is so buried in his work, and in many ways doesn't even realize that he is. He can't see into the future, or much into the past either, at least at the beginning of the book. He spends his days assembling other people's narratives--his clients'--but disattends his own. His mother, Ann, is in many ways the opposite. She prizes intimacy, fellowship, spiritual discernment, and so has the kind of settled quality that lends itself to the more knowing voice of the third person and the past tense.

Assuming you weren't well-versed in immigration law to begin with, how did you go about researching this book, especially when it came to dramatizing the court cases?

A number of my friends from law school went on to do immigration work, so I'd had a view into that world going back to the early aughts, and I had done some volunteer intake work at immigration detention facilities around that same time. I didn't write anything about it then, but once I'd decided Peter would be an asylum lawyer, I started sitting in on immigration hearings at Federal Plaza in Manhattan. They're open to the public, though there was never anyone there except judges, lawyers, and immigrants. So it was basically observational research.

Likewise, did you research intentional communities in order to create Viriditas, the book's feminist spiritual retreat, or is Viriditas entirely homespun?

Likewise, did you research intentional communities in order to create Viriditas, the book's feminist spiritual retreat, or is Viriditas entirely homespun?

The mother of one of my oldest friends from high school actually did something similar to what Ann does in the book. She started a women's retreat center in Maine, which I visited on several occasions. She was someone I knew quite well. Ann's interior life and certainly her family past is entirely my invention, but I did borrow the external facts from the life of my good friend's mother.

Did you have the novel's ending, which is quite perfect, in mind the whole time, or was it hard-won?

I wrote that ending in the last two days before I had to turn in the final manuscript, so it was hard-won! I'd seen it coming, but hadn't been able to reach it, and then once I did, it was only a sketch. I hadn't filled it in to my or my editor Ben George's satisfaction, so on those last days I had one of those very rare, blessed experiences of arriving just in time at what I believed the book needed.

What was the most difficult creative decision you had to make while writing Mothers and Sons?

It was very hard to figure out how to get at Peter's somewhat numb affect. Usually you're trying to make a character vivid, but Peter isn't vivid to himself. Eventually, largely out of frustration, I began writing what turned out to be the opening sections of the book in the courtroom in more or less the same tone as those hearings are in fact conducted. And I discovered that in that very rhythm--an inadvertently callous and somewhat hectic monotony--I'd found a way to enact rather than simply describe his internal state.

If the Internet is to be believed, the shortest period between your books was the six years between the novels Union Atlantic, from 2010, and Imagine Me Gone, from 2016. Do your ideas simply take a while to gestate, or do you give yourself a breather between writing projects? Or do you write a draft right away and then spend years massaging its sentences?

I am indeed slow. Oddly enough, I usually do have some seed of the next book at least soon after I finish the previous one, but then it just takes years of writing, and going down a lot of blind alleys, to even arrive at what, in retrospect, comes to seem like the real beginning, when the thing has quickened, you know you've got something, and then the work gets both more intense but also more gratifying as you push on toward something that will satisfy you by the end. I never write a complete draft. I inch forward, chapter by chapter, editing as I go, and only write the ending at the very end (see above).

What question do you wish an interviewer would ask you, either about this book or about yourself as a writer, and how would you answer?

I wouldn't have said this as a younger writer, but now I like the idea of answering the question, What role does pleasure and/or satisfaction play in the process of writing a book? And I'd answer by saying, early on, it didn't play a large enough role. The self-critical and judgmental voices in my head crowded out the experience of simply writing a sentence the rhythm of which was pleasing to my ear. That's what I love when I read--hearing well-struck sentences, experiencing their satisfactions--so if my job is to write sentences (and that is how I think of it), then why not at least allow oneself the play and the pleasure when you manage that feat well? On the good days, I do that more now than I used to. --Nell Beram