|

|

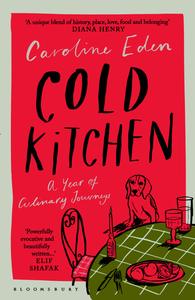

| Caroline Eden (photo: Effie Ioannou) |

|

Caroline Eden is a food and travel journalist based in Edinburgh, Scotland. She is a recipient of the Art of Eating Prize and the André Simon Award. Her previous works, Samarkand, Black Sea, and Red Sands, blend nonfiction topics including food, history, and travel. There is a similar mix of genres to her fourth book, the winsome memoir-with-recipes Cold Kitchen (Bloomsbury; reviewed in this issue).

The focus here, as in your three previous books, is on Eastern Europe and Central Asia. What is it about this region that captivated you and keeps drawing you back?

I first travelled to Central Asia back in 2009 and then slowly fanned out from there, to the Caucasus, Turkey, Russia, Ukraine, and Eastern Europe. There are shared flavors, dishes, and ingredients in the countries that directly border the five Central Asian countries--Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan (for example, in northern Afghanistan and Xinjiang in China, home to the persecuted Muslim Uyghurs)--and also those that were once part of the giant Soviet Union. That was a time when people travelled and worked throughout, between, say, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Georgia, and Uzbekistan.

Language matters, too; the Turkic-speaking world is huge and shares not only words but dishes, so you'll find similar things on the menu in Turkey as you will in Uzbekistan. The same can be said for the Russian-speaking world: if you look at Central Asia and the Caucasus, many people will speak a Turkic language, e.g., Uzbek or Kyrgyz, as well as Russian.

Language matters, too; the Turkic-speaking world is huge and shares not only words but dishes, so you'll find similar things on the menu in Turkey as you will in Uzbekistan. The same can be said for the Russian-speaking world: if you look at Central Asia and the Caucasus, many people will speak a Turkic language, e.g., Uzbek or Kyrgyz, as well as Russian.

Then there are different environmental factors which shape harvests and ingredients and which span manmade borders and different countries. The Black Sea, which I wrote a whole book about, has seen migration and trade for centuries, and the countries that surround it generally share a fondness for herbs, polenta, honey, anchovies, and hazelnuts. It's like a giant jigsaw puzzle shaped by history (think of the Silk Road), geography, language, and religions. And once you start exploring, it is completely addictive.

The book also travels through a year, from winter to autumn. How does the seasonal structure reflect your cooking approach?

I love pickles and tinned food, and I usually cook on a budget, so I don't feel massively impacted by the seasons, though obviously I look forward to things like asparagus and blood oranges. I also switch up the herbs on my kitchen windowsill accordingly: soft herbs in the warmer months; woodier varieties in winter. Here in Edinburgh, it is always quite chilly, though, so much stays constant.

Oddly, it is when I'm in Istanbul, a city I spend a lot of time in, that I tend to pay more attention to the seasons. In winter, for example, I am eager for hamsi (anchovy) dishes, chestnut pilavs (pilafs), and boza, a pudding-like fermented millet drink.

We often hear, in approving tones, that "the world is getting smaller" thanks to social media and globalized culture. Yet we observe xenophobia, restrictions on movement, and severe environmental threats. What do you see as the future of food and travel writing in this context?

I think it's all relative. You might see a nicely curated video on social media of a travel blogger driving across the steppe of Kazakhstan that has had tens of thousands of views, but most people couldn't name the capital of that country. Nor do they have any understanding of how politics is playing out between Russia and China in Kazakhstan today, or how the misery of the environmental fallout of the Aral Sea disaster, which Soviet-era leaders were responsible for, still impacts lives and health.

The job of a writer is to report back and to do so with the utmost respect and empathy, and also not to skirt around the harder issues. Food and travel writing can be many things. It can be whimsical and fun, but it can also cover war, politics, agriculture, animal welfare, the environment, and uncomfortable histories that we have to face up to. A mix is best for the reader, I think!

I loved the way that domestic life contrasts with international adventure throughout the book. How does the one fuel the other, or provide a change of pace or recovery period?

The kitchen is somewhere that entices me home; it is a room that is capable of soothing my pathological restlessness, at least for a while. It is a hitching post. It's also where I write (in a little office off to the side) and obviously where I cook and test recipes. I also know that it is people that make it; I love having friends over to cook for. For me, the kitchen is home.

Which is your favorite dish in the book? What, in your opinion, characterizes a great recipe?

My favorite dish in Cold Kitchen is the layered rice dish plov, in this case with duck and barberry. I was served it in Kyrgyzstan by a relative of my Russian teacher just before huge political upheaval and violence erupted on the streets of the capital, Bishkek, so I remember it well not just because it was delicious.

A great recipe for me is something a little familiar but with a twist, and ideally something from the region I'm interested in. Even better if it symbolizes something interesting. The layered rice dish plov is a sharing dish--one big plate sits at the center of the table--and therefore it symbolizes the genuine and heartfelt hospitality that Central Asia offers.

You find plov throughout Central Asia, and it changes slightly depending on where you eat it. In Uzbekistan, one cook in one town might keep quails and so then you'll likely have quail's eggs on top; if it's autumn, your plov may come with quince. If it's in a fancy restaurant, you might have the option of horse meat. In Azerbaijan in the south Caucasus, given that the country is on the Caspian Sea, fish plov is served, and that is quite hard to find elsewhere. --Rebecca Foster, freelance reviewer, proofreader and blogger at Bookish Beck