|

|

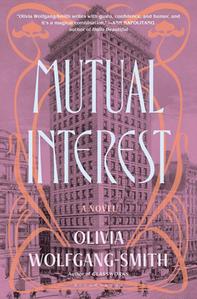

| Olivia Wolfgang-Smith (photo: Bianca Alexis) |

|

New York-based author Olivia Wolfgang-Smith received a 2024 NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellowship in Fiction from the New York Foundation for the Arts. Her debut novel, Glassworks (2023), was longlisted for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize. Her second, Mutual Interest (Bloomsbury, February 4, 2025; reviewed in this issue), is a remarkably fresh historical novel about families won and lost, love, envy, and betrayal.

Mutual Interest draws comparisons to iconic 19th-century authors like Edith Wharton as well as more contemporary figures like Hernan Diaz. How do you work with or against the conventions of social satire when writing?

In terms of Wharton, it's very kind of you to say there's a comparison with her as opposed to that I'm just obviously stealing from her, left and right, in a lot of different ways.

I often describe the book to people as a queer Edith Wharton pastiche. One of the main things is, yes, the social satire piece of her writing, which was huge for me. The seed of humor comes from the highly omniscient narrator who's in cahoots with the reader, laughing at the characters as an affectionate judgment of them and the choices they're making. It's a writing style that I like, and Wharton is definitely in the pantheon of that style.

A great source of pleasure in reading this book is the capable third-person narrative voice. What does this vantage point give you as a writer that others might not ?

It's so fun to just be able to say whatever you want. My first book is very closely aligned with one character's perspective at a time. It's so thrilling as a writer to have this narrator with a 10,000-foot view, who can dive into side characters, who can have a big tangent on geological history, or whatever. Because this book is set at the turn of the 20th century, and it was the convention to have this intrusive style of narrator, that's where I started. But I started enjoying the things that it let me do and the side characters it gave me access to, and the way it let me directly push back on the things that a character says or does--to argue against them a little, to hold them a little bit more accountable.

But it also just shaped the story profoundly, in that this book ended up being about webs of influence, and cause and effect, and the way things snowball and change in a way that is only possible because the narrator has context that the characters don't have.

Does this time period have something specific to communicate to us now?

Does this time period have something specific to communicate to us now?

My entire reading life I've loved these novels of manners, the drawing-room love stories in these very buttoned-up ages that also have a lot of feeling--hormone-driven decisions being made within this very rigid world.

In America, at least, this is the iconic time period where a lot of these are set. I also live in New York City, and this is the most storied era of New York's past, in terms of self-mythologizing. There's a material culture that is preserved and iconic and kind of remixed and discussed everywhere. It's an era of huge technological and social change in a very exciting way.

It's also helpful for me, always, especially in turbulent times like right now, to remember that change is constant and has always been happening and will continue to happen. And that a lot of the times that we live through feel singular because it's the first time we're experiencing them. But the churn of all of this stuff is actually endless and ongoing.

So, it's helpful in that, specifically for New York City, there's always been this tension between relentless change and enthusiasm for change pulling against this mythic nostalgia for the past. Everyone in New York is always talking about how it was better X years ago, whatever that might mean.

What was it like investigating queer histories of that era?

Researching the history of queer community is honestly so fascinating, and it's such a therapeutic joy, because the more that you dig into and find out, the more validation you find in realizing people like this have always existed. No sane person actually thinks that queer people did not exist in the past, but it's just so lovely to see archival evidence of that. It was important to me to get tantalizing archival glimpses of characters who have either not often been present in literature or present only in a sort of fringe way.

In this particular case, these individuals are three spiky people who have a hard time finding community for their own reasons, so there's not as much of what socially functional people might have been doing at the same time.

What role does capitalism have in these characters' lives?

It's totally spot on to say that capitalism is like the water that these characters swim in, a force that's impossible not to define our lives in relationship to, whether we're trying to succeed within it or striving to disrupt it.

I've talked a lot about this book as being about people trying to figure out whether a job can love you back, what are the limits of defining your sense of self and your sense of happiness based on what you produce or achieve in the world, and how you define that.

I've obviously been thinking a lot about "rainbow" capitalism in writing this book and about identity politics--that if you are a queer person you can't possibly do something that would harm queer people

This is another part of what becomes possible when you have a high omniscient narrator: you can point out self-absorption in your characters, and name the things that they're not looking at. And I think that their relationships to capitalism is one of those things. --Elizabeth DeNoma, executive editor, DeNoma Literary Services, Seattle, Wash.