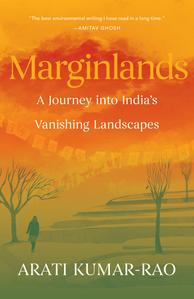

Environmental journalist and photographer Arati Kumar-Rao was named one of the BBC's 100 Influential and Inspiring Women from around the world in 2023. She is currently on a National Geographic grant documenting forced human migration in India. When not on assignment, Kumar-Rao splits her time between a biodiversity hotspot--the Western Ghats--and Bangalore, where she plays a happy mother to three rescued cats. In her debut essay collection, Marginlands: A Journey into India's Vanishing Landscapes (Milkweed; reviewed in this issue) Kumar-Rao demonstrates considerable literary talent in bearing witness to the ecological transformation of her homeland.

Environmental journalist and photographer Arati Kumar-Rao was named one of the BBC's 100 Influential and Inspiring Women from around the world in 2023. She is currently on a National Geographic grant documenting forced human migration in India. When not on assignment, Kumar-Rao splits her time between a biodiversity hotspot--the Western Ghats--and Bangalore, where she plays a happy mother to three rescued cats. In her debut essay collection, Marginlands: A Journey into India's Vanishing Landscapes (Milkweed; reviewed in this issue) Kumar-Rao demonstrates considerable literary talent in bearing witness to the ecological transformation of her homeland.

What inspired you to write Marginlands?

A book was never on my mind, actually. I was documenting these landscapes over the years, going back to places to see how changes were unfolding, photographing all the time. I would post on what was then Twitter and Instagram, and for a while I had a blog called River Diaries, where I would write about the mighty Ganga-Brahmaputra river basin. I guess it caught the eye of publishers and one editor of Pan Macmillan--Teesta Guha Sarkar--approached me with the idea of a book.

Marginlands was published in India in 2023 to critical acclaim. Were you surprised by that? How would you describe the appeal of Marginlands to India's literary community?

I was and am continually surprised when people I don't know at all have read Marginlands. They tell me that the appeal lies in the narrative, which they call "genre-defying." I guess because Marginlands is stories from the field, voices of the people, descriptions of landscapes, and not so much data, statistics, and jargon, it appeals widely. Stories are so powerful.

Being a member of the upper caste allowed you easier access to the people and places you write about. How so? Did being a woman make any difference?

Yes, I was acutely aware of the privileges my caste brought to my fieldwork, especially in places where it is strictly practiced--like in Rajasthan. Equally, being a woman brought with it access I would not have had otherwise. Women practice "purdah," or being veiled, in that state. And so they could not and would not freely speak to a man outside of their immediate family. As a woman, I sat with these women as they cooked in their kitchens, walked with them to the village wells, and was able to get voices from a world that stays largely out of view and out of the discourse. Women's voices tend to be drowned out in stories from these places, and that is something I want to focus on in my current and future work.

You also have an interest in writing fiction. Can you share more about that?

You also have an interest in writing fiction. Can you share more about that?

I would love for these pressing issues of the land to seep into the psyche of a wider audience, for isn't it the land that sustains us? I am increasingly feeling that the way to achieve that is through fiction. Novels, yes, but even more than that, feature films. And that is where I want to concentrate my efforts 2025 onwards.

Is there one person you have met on your travels who has impacted you far beyond anything you could have imagined?

Chhattar Singh, the shepherd-farmer you meet in the first two chapters of Marginlands, taught me how to read the land and how to value--nay, treasure--it. This respect for the land, this attitude of not treating it as a commodity we exploit but as a community we belong to, echoed what my father taught me in my formative years. My father would read to me from Wendell Berry's works and that had a profound impact on my views. When I met Singh, his similarly gentle land ethic seemed to be just what we needed to reclaim in these fraught times.

You describe the understanding of landscapes as being a gradual, layer-by-layer process that requires patience. What was the most challenging aspect of this method for you?

Funding! How does one find the resources to conduct such slow, long-term, longitudinal storytelling of the land? The appetite for slow journalism is virtually non-existent in India. People like Prem Panicker (then the editor of Yahoo! Media, who gave me a chance and funded River Diaries) and Rohini Nilekani, who sponsored research and travel for Marginlands, are few and far between. The art of long-term, long-form storytelling is the need of the hour. We need to both walk stories back in time and stay with stories in the present to understand how we got to where we are, so that we may glean the way forward. To do this well takes resources.

Is there a role for Indian folklore in the environmental stories you share?

I have come to realize in the last few years how stilted so much of our folklore is, how patriarchal, how inequitable, and how utterly unscientific. Women and animals, forests and landscapes, forest dwellers and indigenous people tend to be vilified in a thousand ways. So much so that those sentiments have insidiously crept into our language. The famous Igbo proverb comes to mind: until the Lions have their historians, the glory of the hunt will always belong to the Hunter. Similarly, unless we rewrite some of our myths and folklore, we will forever imagine important landscapes and their denizens as cunning, evil, vicious, and something to be done away with.

What is your ultimate hope for the future of India's natural world?

Aldo Leopold's words from A Sand Country Almanac (1949) are even more pertinent today: "Civilization has so cluttered this elemental man-earth relationship with gadgets and middlemen that awareness of it is growing dim. We fancy that industry supports us, forgetting what supports industry."

This is my hope for India and the world: that we may reacquaint ourselves with the land and reclaim a land ethic that respects and values the very thing that sustains us. --Shahina Piyarali