|

|

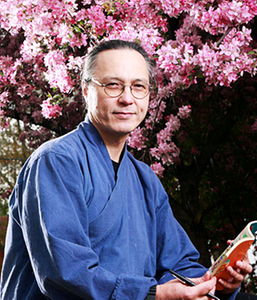

| Heinz Insu Fenkl (photo: Peter Lueders) |

|

Heinz Insu Fenkl writes and translates across genres. His latest project is Snowy Day and Other Stories (Penguin Press; reviewed in this issue) by lauded Korean filmmaker Lee Chang-dong, which he co-translated with Yoosup Chang. Written in the 1980s, long before Lee became a globally revered auteur, the seven stories here feel just as contemporary almost a half-century later as political upheavals and conflagrations continue across the globe.

Your translator's note reveals the provenance of your 20-year history with Lee's work. Could you share some of that background?

I found Lee's first story, "The Dreaming Beast," by accident because it was in a literary journal that came free of charge with a Korean women's magazine my mother used to buy at the Korean grocery in Marina, Calif. It had that quality of being easy to visualize--something that happens when you get absorbed in a story. When I went to Korea for my Fulbright in 1984, I thought I'd try doing some translation, and that's how I got started with Lee's work. I stopped after a few pages, and then I didn't pick up the story again until the 2007 inaugural issue of Azalea [Korean literature and culture journal published by Harvard's Korean Institute].

Lee was inspired by specific Korean events. Do you think Western readers need to be familiar with that history to appreciate these stories now?

I think readers who already know something about modern Korean history will understand the context of those stories quite well. For Anglophone readers in general, it would probably help if they knew about the events that followed the assassination of Park Chung-hee and the martial law that followed when Park's former general, Chun Doo-hwan, took over. The Gwangju Uprising in 1980 and the massacre of civilians by the Korean military was a major turning point in national sentiment, especially in relation to Koreans' attitudes toward the U.S. The Uprising was part of the democratization movement protesting the authoritarian take-over by Chun, and the leaders of the Uprising had appealed to the U.S. for help. When there was no intervention, they felt betrayed, and the almost universal pro-American attitude that followed the Korean War practically vanished in a few years. The impact of the Gwangju Massacre on Koreans is still profoundly felt today.

Since you grew up in Korea during these dictatorial regimes, was working on these stories triggering for you?

I grew up during Park Chung-hee's administration when the Saema'eul Movement ("New Community Movement") was in full swing. That's when there was a surge of national development of infrastructure and industry at a terrible cost to the environment and to people's lives. I was only a child, so I didn't understand the full political implications, and I was insulated from much of it because I spent most of my time on U.S. military bases and in the camptowns (Bupyeong and Itaewon). I did witness police brutality firsthand. The curfew just seemed to be a fact of life at the time, and I had a cousin who got into trouble for little things like having hair that was too long or for smoking American cigarettes. My mother was a black marketeer, so by association (sometimes helping her), I also saw how things worked with law enforcement on both the Korean and U.S. military sides. That was from the late 1960s into the early 1970s and is part of what I explore in my novel Skull Water.

Lee's stories are set in the early-to-mid 1980s, which would be a decade later, but much of the political climate had not changed. The daily life, and the conditions--political and economic--of postwar Korea also had not changed much. The families in his stories are on the margins of society (usually because some family member is associated with accusations of being a communist sympathizer), and my family was also always on the margins. My mother was also constantly in debt and the houses I lived in were visited regularly by debt collectors, black marketeers, and prostitutes, so the theme of living on the fringes of society resonated very strongly for me.

You're a writer as well as a translator. How different is your process between the two?

I described my translation process as a kind of "method acting" to Lee Chang-dong, and he told me that was the most accurate analogy for it he had ever heard. Before I translate a story or a novel, I read it several times so that I understand the feel, the style, and the tone of the language (since I must re-create an analogous style in English). But that means I also have to immerse myself in the things the story or novel is alluding to (which is why it took me more than a decade to translate Kim Man-jung's The Nine Cloud Dream, a 17th-century Korean novel written in Tang Chinese).

After translating for many years, I discovered that the process in my own writing isn't all that different. I begin by immersing myself in the story (and since so much of my writing is autobiographical, that means in my memories of the past), then I have to convey images and emotions in language. So I realized that I'm also "translating" my own experiences in much the same way in my own writing.

Between my novels Memories of My Ghost Brother and Skull Water, I was engaged primarily in translating and writing about Asian American and Korean literature, so I learned a great deal from writers like Hwang Sun-won, Yi Mun-yol, Pyun Hye-young, and, of course, Lee Chang-dong. All of them have distinct styles, and translating them in many ways was also a process of studying and learning from them. All that experience influenced my own work. What's distinct about Lee's writing for me is that his ability to visualize (the "narratography" of his writing, as I've called it) is very parallel to my own visual imagination. His stories, when I remember them, feel like memories from my own life experience.

How did you and your co-translator Yoosup Chang divide the work?

For the stories we co-translated, Yoosup would do a first draft at the same time I was doing my first draft. He would keep his draft very literal (adding notes for particular difficulties, especially things that needed contextual cues or were figures of speech). Then we would go back and forth editing together until we had a final draft. At that point, I would copyedit it as if it were written in English.

One of the reasons I've worked with Yoosup Chang is that he's a decade or so younger than I am, and he has an excellent command of contemporary colloquial Korean. I'm especially good at translating works that come out of the Japanese colonial era and post-Korean War period because that's the language I heard as a child, which was still being spoken into the early 1970s. --Terry Hong