|

|

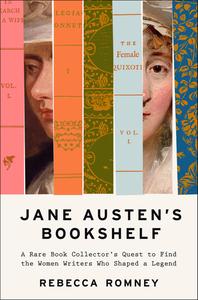

| Rebecca Romney (photo: Donnamaria R. Jones) |

|

Rare book dealer Rebecca Romney has appeared on the History Channel's Pawn Stars--a cameo she made, in part, to dispel the myth that book-collecting is a male-dominated field. One might say that myth-busting is a primary motive behind her nonfiction book Jane Austen's Bookshelf (Marysue Rucci Books). Austen was a genius, but not a lone genius; her work unfolds in conversation with other gifted women writers. Romney spoke with Shelf Awareness about life as a rare book dealer and reader, and how important it is to stay open when making new discoveries. She lives in Washington, D.C.

Jane Austen's Bookshelf began with your discovery, on a house call, of a copy of Evelina by Frances Burney. A passage from another novel, Cecilia, by Burney appeared in Northanger Abbey, and gave you the roadmap for your book. What was it like to find a book that opens up such possibilities?

That feeling is something that has nourished me in my work as a rare book dealer. I can't manufacture my product. I have to find it. You have to be both looking, and also open to what you find, especially if it's different than what you expected.

That same thing can be applied to our reading. Books can say so many different things to us depending on where we are at any given time. I'd read [Northanger Abbey] multiple times, and finally I feel like I heard [Austen]. It made me feel even closer to her because I felt like I was finally hearing something that she wanted to say that I couldn't before.

What first drew you to rare book dealing?

I did not know this was a career that existed before I stumbled upon a job listing to become a rare bookseller. When the opportunity had presented itself, I ended up realizing that I had accidentally prepared myself for it the entire time.

I grew up in Idaho, very far away from places like the Morgan Library. I did not think those places were for me, that they could enrich my daily life. And I was wrong. Those ideas were myths that are just not true. A lot of us are convinced that reading can be transformative. I wanted to use [my] book to show how book collecting can do the same thing, and that it is accessible in the way that you are already finding reading accessible--as a way to reach those points of enrichment.

One especially enjoyable thread in the book is your investigation of the phrase "pride and prejudice." Did you ever land on the origin of it?

One especially enjoyable thread in the book is your investigation of the phrase "pride and prejudice." Did you ever land on the origin of it?

No. I have only a circumstantial case. And I feel like that's what we get when we're looking at history. We build our narrative. And whether that is accurate is a question that is in some ways not useful, because the history is gone. But what I think is likely is that Cecilia came out; it was a really big book at the time. It's the first one of all these appearances [of "pride and prejudice"].

The passage in [the journal of Hester Lynch Thrale] Piozzi was [dated] the same year as Cecilia [by Frances Burney]. And Piozzi was very close to Burney. So it wouldn't surprise me at all if she was comparing herself to the plot in Cecilia. She's talking about whether or not she should marry [Gabriel Mario Piozzi], that all of her friends have this pride that she shouldn't marry him. So in some way, she is criticizing her friend's advice to her, based on her friend's own book.

Similarly [Charlotte Smith's] Old Manor House comes later and, again, I would be shocked if Smith hadn't read Cecilia at least once, if not multiple times. I do think it is still a possibility that was just a phrase [used at that time]. But I think given how tightly networked the literary world was in that era, it is most likely that Burney is the originator. And that's why even now I kind of still say Austen probably got it from Burney.

You also discuss the way language evolves over time. The term "romance" once meant any work with fantastical elements, like A Midsummer Night's Dream and even H.G. Wells's "scientific romances." It came to mean something quite different, a step beyond what you refer to as the "courtship novels" that Austen and her predecessors wrote. How do you think this evolution contributed to the fact that even Austen fans may not know of the women writers she read and reacted to?

I talk about a lot of that stuff with romance, because I was grappling with my own biases. Why would I be interested in this? I realized that in fact it was aimed at women and communicated women's issues and needs. That was a feature, not a bug. When you start to look at this as one big literary tree of women talking to each other, you realize that there are women who understood a lot of the things that you feel, moving through life.

I believe very strongly in the idea of autobiographical reading. I don't think you can approach a text without putting yourself into it in some way. And so instead of pretending that's not the case, I would rather talk about it, reveal it and explore it.

How soon did you recognize this pattern of taste makers--people like dictionary author Samuel Johnson and Shakespearean actor David Garrick--in that time and how that continued to build on itself in the creation of the literary canon?

I talk about this very early, in the Charlotte Lennox chapter, where I was beginning to see these patterns play out. Every woman's story was different and complex and compelling in its own way. I think that there is an easy way to answer the question, why don't we read these women writers anymore? The easy and glib answer is sexism. But, in fact, the reason that this is a book is because it's more complex than that, and in fascinating ways that deserve to be explored. Glibness really does it a disservice.

Austen is not demeaned by the fact that these other writers are great, too. We use comparison to rank rather than reveal. This is the beginning of a conversation--not letting go of the mic.

One of my favorite quotes of yours is, "A reader falls in love with the story in the book. A collector falls in love with the story of the book." In Jane Austen's Bookshelf, you allow yourself to be both.

I have a very distinctive sense of what reading is versus collecting. I describe and structure that upfront, in order to define those terms for readers. There are a lot of people who think that they're only readers, who don't realize they're actually collectors. I gave the example of the teen whose favorite book is The Hunger Games. They start collecting all these different editions. As soon as you're buying a book not to read the text, but for some other reason, you're collecting. Do you have two copies of the same book? If so, you're a collector.

I co-founded a book collecting prize, the Honey & Wax Prize. It's an annual prize of $1,000 for a woman in the United States, aged 30 and younger, to encourage women to have more ownership and more pride in that, and to name it.

To me, the reading and the collecting side are distinct and synergistic. They influence each other. They are mutually beneficial even if they are technically distinct. --Jennifer M. Brown