|

|

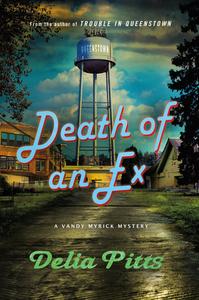

| Delia Pitts (photo: Steven C. Pitts) |

|

Delia Pitts interned at the Chicago Sun-Times before spending 11 years as a diplomat in the United States Foreign Service, serving in U.S. embassies in Nigeria, Mauritania, and Mexico City, along with Washington, D.C., assignments. She later worked as a university administrator before becoming a full-time writer. Death of an Ex (Minotaur; reviewed in this issue) is her second novel about Evander "Vandy" Myrick, the only Black private detective in Queenstown, N.J.

Your series is about Evander "Vandy" Myrick, a former police officer turned private detective in Queenstown, N.J. What was your inspiration for your character?

I started with my own family. I have an older cousin, Esther, who, with her husband, started a small detective agency on the south side of Chicago during the 1960s. They handled things like personal security, security for property, and insurance fraud, nothing violent. Esther was inspiring because at the time not a lot of women, especially Black women, were running private enterprises, certainly not in the area of security. She made me think that a lot things were possible. Esther's last name is Myrick so Vandy is definitely named after her.

How did you shape Vandy?

I wanted her to be an African American woman of a certain age, a woman who is not in her first youth but is still vigorous and lively, funny, sexy, and hard driving. I wanted to create a world for her to go back to when there's a turn in her life.

I wanted her to have the confidence to be a plausible action hero so she's an ex-cop who served on the New Brunswick force, and with the Rutgers campus police. When we meet her [in Trouble in Queenstown] she's had a significant decade of professional law enforcement. She's not a novice in terms of work, experience or her age--she's 48. Her father was a cop, the only Black cop in Queenstown, and she's named after him. He wanted her to be a police officer. When she followed her father's footsteps, she was enforcing his vision of what she could be.

Why is it important to include Vandy's ongoing grief over the death of her 20-year-old daughter, Monica?

The horrendous loss of her daughter is the searing wound that impacts her. It marks her, it gravely wounds her. But the death of her child doesn't define all that she is. She is so much more, larger than that one great tragedy that upended her world. But it is that tragedy that uproots her and she comes back to Queenstown where she grew up to start life again.

So often in books, we see people have life-changing trauma but in the next episode or chapter, they are fine. There are shades and stages of grief and we are seeing Vandy in a different stage of grief--it's been three years--so it's not hitting her the same way it would at the beginning. But the grief is still there. It would not be fair to the nature of grief or to the character of Vandy to just forget and leave it behind. Part of the process for her are the promises she made to her daughter. She doesn't drink alcohol nor carry a gun. In Death of an Ex, I wanted to give her a new level of emotional engagement, to rein in how she deals with grief, and that includes how she deals with her ex-husband who was Monica's father.

I wanted to give her a rich and complicated background to explain her skill set and her psychology. She is a person who has lost everything. And that is where we move in with her.

Why did you choose the small fictional town of Queenstown as your setting?

A small town gives me more opportunities to explore an area. Having characters reoccur in the context of a novel and across the series can make for richer presentation, and more fun. Often, these side characters--and they don't think of themselves as side characters--will give a crucial bit of information and then go away until it's time for them to come back. That's also how a community works. You see people, but then may not see them for a week or a month. Your view of them changes as they walk in and out of your life. That lends itself to the truthfulness of life. There's only about 9,000 people in Queenstown as I have described it, and about 2,000 or less are African American. But the town has a rich history of African Americans living and working there, going back to pre-Revolutionary days.

What drew you to the private detective novel and what makes Vandy different from other private detectives?

What drew you to the private detective novel and what makes Vandy different from other private detectives?

The private detective attracts me because it compellingly speaks to the role of the individual in society--the power and the responsibility to stand for the values of a community but also to stand against the community when necessary. I like the flexibility that the private eye gives us. They straddle both sides of the legal line of law enforcement, dancing from one side to the other, exercising judgment, morality. Vandy knows quite well what police procedural is, but her responsibility is individually to her client and more broadly to the community. She knows sometimes those responsibilities are conflict with the law.

I made a conscious effort to make Vandy grow from the tropes of the detective novel but to move against them. Most of those PIs are loners, but I wanted to build a circle of community for her with people who support her. Vandy's reliance on those friends she grew up with, went to college with, is very important. This set of strong women friends translates to mentoring teenager Ingrid Ramírez. While she does have an eye for the gentlemen, she doesn't drink nor carry a gun--both promises she made to her daughter. A gun also is an invitation to violence.

How does your background influence your writing?

My time in the Foreign Service expanded my capacity to write on deadline. I was often the junior member of the team so it was my responsibility to write the proceedings of the conference, and to do that quickly and with great accuracy. That means I learned to listen carefully, to hear what was being said, but also what was intended, the subtle tones being taken by the participants. That is essential to being a good writer and a good fiction writer. I learned how rhetoric plays into the presentation and how language can be used in a variety of ways and settings. I think all writing is persuasive, to move the ideas I have in my head into the head of the reader, to persuade them of the message's depth.

Naturally, the fiction message is quite different. I wasn't writing fiction when I wrote a report on the education system of Mexico to be sent to Washington. But I was still trying to persuade the decision makers of the truths I had uncovered. I wrote many speeches for ambassadors and that means pressure and voice. Voice is very important for characters. In speeches I was writing in the voice of the ambassador, not my own voice. It's very important to translate the vocabulary, background and concerns of the ambassador into their voice. I had to step into the voice of another person. That's an important skill in fiction. --Oline H. Cogdill, freelance reviewer