|

|

| Daniel Miyares | |

Daniel Miyares is an author and illustrator who has illustrated numerous books for young readers, including That Is My Dream! by Langston Hughes; Nell Plants a Tree by Anne Wynter; and Hope at Sea and Night Out, both of which he also wrote. He lives in Lenexa, Kan., with his family and their dog.

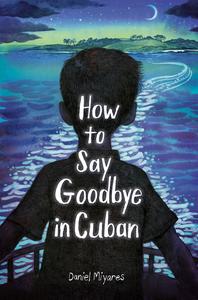

Miyares spoke with Shelf Awareness about his first graphic novel, How to Say Goodbye in Cuban (Anne Schwartz Books). Here, Miyares discusses how he researched Cuban history and adapted his family's story, what it was like to write and illustrate a graphic novel for the first time, his methods for showing authenticity, and the importance of making books like his available to children.

Please tell our readers a bit about How to Say Goodbye in Cuban.

How to Say Goodbye in Cuban is my first-ever graphic novel and it's based on the stories my father told me about his escape from Cuba as a boy, just after the Cuban revolution.

What does the title mean to you and what does it mean in the context of this book?

For a long time, this book remained untitled. Maybe it was because the scale of the project was new to me, but it seemed like there were almost too many emotional threads in the story to try and encapsulate them all. My list of possible titles was long but none of them felt just right. It was actually Anne Schwartz who suggested How to Say Goodbye in Cuban. What I loved about it was the acknowledgment of the tough choices that the family had to make. That was a central idea that kept ringing in my ears the entire time I worked on this book. What was it that drove my grandfather to make the choice to uproot his entire family and flee their homeland? And what must that have been like for my dad and his siblings?

How old was your father at the time of the story? You note that you aged him up--why?

How old was your father at the time of the story? You note that you aged him up--why?

My father was six to nine years old when the stories took place, and I made him about 12. Mainly I wanted him to have more agency, which I thought the reader might be able to relate to more. With so much happening to him that was outside of his control, it felt like Carlos needed to be able to ask challenging questions and share his emotions during it all.

There's a ton of detail here; is it all factual? How did you write the dialogue?

I tried to be as factual as possible. There are certainly some story elements that are fictionalized--especially if there were holes in what my dad remembered, or the story needed to be simplified for clarity. Like my dad told me that he and his friends from the neighborhood would go into the nearby woods and catch tarantulas. He remembered how they would catch them, but when I asked him what those friends names were, he couldn't remember, so I made up their names for the sake of the story. A lot of the dialogue is inspired by how my dad described how he felt about certain moments or events. There are a few places where he remembered very specific conversations or things that people said. I tried to include those where I could.

One thing that ultimately helped me in writing the dialogue was creating a board in my studio that broke down each chapter into character motivations. At a glance I could see how the intentions of each person shifted throughout the story. Then I could really begin to imagine the dialogue that would drive the events my dad described. But no matter where I ended up with plot or dialogue, it all had to be put through the filter of historical context and research.

In between events in your father's story, you include facts about Fidel Castro and the Cuban Revolution. How did you break the story down into its individual parts?

When I looked over all the stories I had collected from my dad, they weren't linear. It was more like episodes from his life that had resurfaced where they wanted. I first had to organize them chronologically, then decide what to include and what to leave out. Once I settled on telling the story from my father's perspective with him as the narrator it gave me the freedom to begin editing. In the end, I could only share things that Carlos would have known about as a kid at the time.

How did you decide which facts would go with which parts of the story?

After I had the chapters outlined, I then went back to the beginning and did a deep dive on historical accounts of the Cuban revolution. As I researched, I made notes of all the ways the revolution had intersected with the stories from my dad's interviews: if he mentioned ration books being used in the house, I kept an eye out for that in my historical research. With a pretty strong timeline in place for the revolution I could then make choices about what information to include before the start of each chapter. My goal was to have those bits help inform the reader but also reinforce and give weight to the experiences of the family in the proceeding chapter.

Because this is a graphic novel, so much of the story is told through format--why did you decide on hand-lettering?

Normally when I make a book, I really want to use every aspect of the reading experience to support the story. I don't want to give the reader any excuse to exit the flow of the book. The lettering was meant to have the same hand-drawn authentic feel as the artwork. I hand-lettered the title and some punch words, but for the rest of the text my fabulous designer/art director partner Juliet Goodman offered to make a font from my hand lettering. So, I hand-drew the characters needed for her to do that.

The panels, too. They all look hand-drawn.

Yes! I hand drew and painted all the art and panels.

Hand-creating all the artwork and lettering for the book was challenging and it took a tremendous amount of time, but it made me feel intimately connected to the story. I hope the reader feels that same authenticity when they hold the book in their hands. This was also my first time working on a graphic novel. Since the form was new to me, I wanted to be able to fully appreciate all the elements that could be used to tell the story. Doing all the layout drawings on paper by hand really did that.

Have you considered adding onto the story?

I have certainly thought about it. Unfortunately, my dad passed away while I was working on this book. If I did attempt another story, it would need to have a different focus. Their journey didn't end once they got to the U.S., so I wouldn't rule it out.

Why write this for a young reader audience?

My dad went through these things when he was the age of a young reader. My hope is that kids might be able to either relate to those experiences or see that not everyone has had the same experiences as them.

Is there anything else you'd like to tell our readers?

Thank you all so much for considering and supporting stories like these. In a time when fear of outsiders is being used so loudly as a political tool, I believe it's extremely important to make space for empathy. I suspect that most people that leave their homeland for someplace new just want what most of us want--a better life for their family. --Siân Gaetano, children's and YA editor, Shelf Awareness