Friday, October 6, 2023

We have some star-worthy fiction that defy genres this week: in the "charming and humorous fantasy-mystery" The Hexologists by Josiah Bancroft, a married couple uses investigative skills, arcane arts, and a magic carpetbag to solve a case that threatens a kingdom; and Mohawk author Alicia Elliott spotlights mental health, new motherhood, and family resilience in And Then She Fell, her "bitingly hilarious, spine-tingling, genre-blurring" fiction debut. Plus, three creators--Jason Reynolds, Jerome Pumphrey and Jarrett Pumphrey "at the toe-tapping tip-toppest of their game"--deliver a "soulful tribute to a beloved poet, essayist, and cultural leader in the melodic" There Was a Party for Langston. And so many more!

In "From Page to (Small) Screen," we have a preview of two favorite books making their move to limited series this season: Lessons in Chemistry and All the Light We Cannot See.

And Then She Fell

by Alicia Elliott

Mohawk author Alicia Elliott (A Mind Spread Out on the Ground) spotlights mental health, new motherhood, and family resilience in And Then She Fell, her bitingly hilarious, spine-tingling, genre-blurring fiction debut. Thirteen-year-old Alice gets talked out of a bad date by an unlikely counselor: Disney's Pocahontas, who gives the shocked Mohawk teenager a snarky lecture through her TV screen. Adult Alice lives in a stylish Toronto home with her husband, Steve, a white professor who happens to specialize in Mohawk culture, and their new baby, Dawn. She struggles to bond with the baby and tamp down her sense of injustice as Steve learns the Mohawk language to further his career. She thinks, "When you both die, Steve will have to translate your ancestors' words to you." Alice is also awash in grief after her mother's recent death, and grappling with doubt as she writes a modern version of the Haudenosaunee Creation Story. The mental wall she learned to erect as a teen has eroded, and she hears the voices of trees and a bathroom cockroach. Alice--and readers--are left wondering whether she's losing her sanity or discovering a new aspect of reality.

Elliott's ambitious, enthralling portrait of a brilliant young woman beset with racism, postpartum depression, and grief reminds readers that the truth is often multilayered. This provocative blend of drama and speculative fiction is charged with justified anger and overlaid with Indigenous stories and characters. Book clubs should consider this feminist parable a first choice. --Jaclyn Fulwood, blogger at Infinite Reads

Discover: In an ambitious and enthralling novel, a young Mohawk woman navigating grief and new motherhood has experiences that could signify a break with reality, or a new reality altogether.

The Golem of Brooklyn

by Adam Mansbach

An art teacher, a bodega clerk, and a giant monster made of clay walk into a white nationalist rally in Kentucky. Readers may think they've heard this one before--but they haven't. This is the plot of Adam Mansbach's often hilarious and sometimes tragic The Golem of Brooklyn in which Len, a very stoned art teacher, accidentally creates a golem, a devastating creature of Jewish folklore that protects the Jewish people. Len is unable to speak Yiddish and can't understand the creature, so he recruits Miri, a neighborhood bodega employee whom he's heard curse people out in Yiddish; he figures she's suited for the job. Once the golem is told about the current state of affairs for Jews in America, it knows what it has to do--and what it has to do is violent. So begins a cascading adventure as these two misfits figure out how to control and direct a walking weapon for the Jewish people and consider whether they should "repair the world" or help destroy it.

Mansbach (The Devil's Bag Man; The Dead Run; Rage Is Back) tells a story that is a ridiculous but compassionate ride from start to finish--and is the kind of funny that will make readers cackle. Len and Miri are infinitely lovable, anxious, and complicated characters who propel the story. Some portions of the novel that explain the history of the golem feel a little more forced, but they don't detract from this literary adventure of mythic and uproarious proportions. --Dominic Charles Howarth, book manager, Book + Bottle

Discover: The Golem of Brooklyn, while never losing its compassionate lens,fuses madcap humor and Jewish folklore to create a literary adventure of mythic and hilarious proportions.

Ladies' Lunch: And Other Stories

by Lore Segal

Lore Segal celebrates with humor and grace the friendships that stand the test of time and the particular eccentricities of aging in Ladies' Lunch and Other Stories. Featuring fictional pieces, some collected from earlier publications, as well as previously unpublished memoir excerpts, Ladies' Lunch begins with nine interconnected dramas starring five sassy New York dames who have met for lunch every other month, for more than 30 years, at one another's well-appointed Manhattan apartments.

Ruth, Bridget, Farah, Lotte, and Bessie possess an enviable air of freedom about them. Appetites may be waning but their senses of humor remain firmly intact. Their spouses are long gone, apart from Bessie's second husband, Colin, whom no one can stand. Professional career women back in their day, the friends cheerfully attend shivas, wakes, and funerals, "the cocktail parties of the old" where they drink martinis and sometimes forget that they are not at an actual party.

Now in her 90s, Segal (Shakespeare's Kitchen; Half the Kingdom) is the celebrated author of novels, short stories, and children's books written over the course of six prolific decades. In "Pneumonia Chronicles," one of the half dozen pieces in the latter ("Other Stories") part of the collection, Segal describes in entertaining, tragicomic detail an extended hospital stay during the Covid-19 pandemic and her unlikely friendship with a young male nurse that blossoms over their shared love of Anton Chekhov's short stories. As she marvels at this unexpected bonding, Segal's joy underscores a perspective that is the key to graceful, courageous aging and that permeates this entire entertaining collection. --Shahina Piyarali, reviewer

Discover: Lore Segal's witty, entertaining stories set in Manhattan feature five elderly ladies who lunch--and hatch a plan to rescue one of them from a nursing home--plus other astutely rendered selections.

Brooklyn Crime Novel

by Jonathan Lethem

In Brooklyn Crime Novel, Jonathan Lethem (The Arrest) returns to the neighborhood of Boerum Hill, the setting for his novels Motherless Brooklyn and The Fortress of Solitude, and the place where he grew up in the 1970s. He discards conventional structure in favor of more than 100 brief passages that, taken together, paint a comprehensive, if decidedly idiosyncratic, social and economic portrait of his native borough over the half-century since his youth.

When it comes to the "crime" in the novel's title, Lethem concentrates on the broad subject of petty street theft that, in significant part, defines the interactions between the white teenagers who grow up on Boerum Hill's Dean Street and their Black counterparts in the neighborhood and nearby projects. All of this is acted out in something called "the dance"--shorthand for the nonviolent, but coerced, exchange of small amounts of cash between the more and less powerful. It's only in the novel's penultimate section, when a pair of shocking incidents leap the boundaries of this well-choreographed system, that the fundamental flaw in its logic is revealed.

Lethem's narrator hopscotches from one episode and time period to another, at first speaking from a detached position, but then gradually situating himself as more of a character in the story. Through the slow accretion of detail that clearly draws on Lethem's boyhood experiences, the novel becomes a sociological study of a neighborhood undergoing a tense transition, especially as gentrification and skyrocketing property values arrive when the "Brownstoner era" begins to emerge in the late 1970s. --Harvey Freedenberg, freelance reviewer

Discover: Jonathan Lethem creates a vivid portrait of the borough of Brooklyn over 50 years of profound social and economic change.

Mystery & Thriller

Valley of Refuge

by John Teschner

John Teschner (Project Namahana) continues his exploration of the dark side of Hawaii in the insightful techno-thriller Valley of Refuge. The novel juxtaposes two characters with vastly different ideas about how the land should be treated. Franky Dalton started as a Peace Corps volunteer, bringing Internet and computer skills to remote African villages. Now, 15 years later, he is a billionaire techno-industrialist who wants to pave paradise to build his exclusive "Sanctuary," an advanced marine research center on a remote Hawaiian island. But the land Dalton covets belongs to Nalani Kanahele Winthrop and her family. Despite the life-changing money being offered, the family does not want to give up the ancestral land that means more to them than cash. The Hawaiian island is also the destination of Janice Diaz, shuttled from an airplane to a hospital with only a locked cell phone and a passport, and no memory of her past. Teschner expertly reveals her past, and why she lands on the island.

Teschner deftly contrasts his characters' motives against the backdrop of Hawaii's seamy side, depicting how Dalton became driven by his ego, going from a volunteer with pure ideals to a megalomaniac who is unconcerned about others or land destruction. Dalton thinks he is a good man, trying to protect his family and building a future for his wife and twin sons. He is wrong. Nalani could be seduced by wealth, but she believes the past is more important. Strong characters coupled with solid action flow throughout Valley of Refuge. --Oline H. Cogdill, freelance reviewer

Discover: In this insightful thriller, a family that wants to preserve their ancestral land thwarts a billionaire's plan to take over a remote Hawaiian island.

A Traitor in Whitehall

by Julia Kelly

Julia Kelly (The Last Garden in England) turns her hand to mystery in her twisty, engaging sixth historical novel, A Traitor in Whitehall, which takes readers into the heart of London's cabinet war rooms during World War II. Evelyne Redfern isn't thrilled with her job at a munitions factory, though she's proud to be doing her bit. But a mysterious interview with an old friend of her father's leads to a job at the cabinet war rooms, where she becomes part of the typing pool and also (secretly) keeps her eyes peeled for information. Days later, one of her fellow typists is murdered, and Evie finds the body. Determined to catch the killer, she teams up with David Poole, an aide with a secret assignment of his own: to find both the murderer and a mole who may be leaking vital information to the Germans.

Kelly's narrative zips along, taking Evie from the cabinet war rooms to various parts of London (even dodging Nazi bombs, when necessary) and back to the boardinghouse where she shares a room with her friend Moira and stacks of mystery novels. Kelly layers her story with plenty of historical details, including the fashions of the day and the complicated structure (physical and political) of the cabinet war rooms. Evie is a smart, compassionate sleuth with a deep interest in her fellow workers, and her prickly dynamic with David eventually grows into mutual respect. Evie's first adventure is a well-plotted start to an entertaining new series. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams

Discover: Historical novelist Julia Kelly launches a mystery series with an engaging heroine who works as a typist in Winston Churchill's cabinet war rooms.

The Death of Us

by Lori Rader-Day

Parenting issues take center stage in Lori Rader-Day's thoughtful domestic thriller The Death of Us, which examines the definition of family and what makes a parent. Liss and Link Kehoe had been married only a couple of months when Ashley Hay, Link's former lover, showed up and handed Callan, Link's infant, to Liss. Ashley then disappeared. Liss has made Callan the center of her life for 15 years, giving him emotional support, cheering him at sporting events, and ferrying him to school and activities. She has been Callan's main parent, but legally she's unable to adopt him because Ashley might return.

But then Ashley's remains are found in a car submerged in a water-filled quarry near the family's home. Ashley didn't drown--someone murdered her, and Liss and Link, now separated, become immediate suspects. Town marshal Mercer Alarie learns that the former marshal--Link's father, now suffering from a neurological illness--did not thoroughly investigate Ashley's disappearance. And Liss's romantic relationship with Mercer further hampers the case. Rader-Day (Death at Greenway) ramps up the suspense with strong, believable characters in complicated relationships. Liss's love for Callan is pure, but her estrangement from Link shows her how little currency she has with her in-laws or her colleagues in the guidance office at the high school where she works. Link, a serial cheater, ignores the chaos he creates. Rader-Day expertly leads the solid plot of The Death of Us to a satisfying denouement. --Oline H. Cogdill, freelance reviewer

Discover: The discovery of a woman's body brings a troubled family further turmoil in this thoughtful, satisfying domestic thriller.

Murder Most Royal

by SJ Bennett

In the third installment of the engaging Her Majesty the Queen Investigates series, British author SJ Bennett (The Windsor Knot) whisks readers to rural Norfolk and the royal Sandringham Estate. Here, Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip, both ill, have arrived to spend the Christmas holidays with assorted family members and staff. When she learns a severed hand has been discovered on the local beach, Elizabeth is determined to let the police handle the matter while she copes with her flu and focuses on the holidays. Then a questionable hit-and-run lands an influential villager in the hospital. The Queen and Rozie, her assistant private secretary, begin an investigation of events. Local aristocratic landowners carefully paint wholesome, uncomplicated versions of their lives for Rozie, but the Queen remembers which family members may have had reason to want a member of their elite circle dead. The police have identified the hand, which belongs to an aristocratic landowner, but cannot locate the body. It will take the combined efforts of Rozie's investigative skills and the Queen's shrewd deductive talents to sift through the tenuous clues and identify the murderer.

Vivid descriptions of Norfolk's wintry landscape provide sharp contrast to the glamorous world inside Sandringham House and the trappings of royal life. The author's affection for the iconic Queen is on full display in multiple scenes that feature Elizabeth's practicality and astute discernment of human character, lifelong passion for country life, deep involvement with family, and undeniable wit. Although part of an ongoing series, this lively, delightful novel can easily be read as a stand-alone title. --Lois Faye Dyer, writer and reviewer

Discover: When Queen Elizabeth II travels to her Sandringham Estate to enjoy the Christmas holidays, she's caught up in solving a complicated murder that may hit too close to home.

Science Fiction & Fantasy

The Hexologists

by Josiah Bancroft

A married couple uses a combination of investigative skills, arcane arts, and a magic carpetbag to solve a case that threatens a kingdom in the charming and humorous fantasy-mystery The Hexologists by Josiah Bancroft (Senlin Ascends), the first novel in a series with the same name. Isolde Ann Always Wilby, a woman "often described as imposing... because she had a way of imposing her will upon others," and her gregarious "garden wall" of a husband, Warren, make up the sleuthing duo of the novel's title; they practice hexegy, a "shallow rill" of practical magic in a world that has all but banned magicians and necromancers, and reveres alchemists. The hexologists fall into a royal muddle when the king's secretary confides to them that His Majesty wishes to be baked into a cake, possibly due to a claim that the king fathered an illegitimate child in his youth. Iz is reluctant to work for the monarchy until Warren reminds her that suffering on high will trickle down to the poor. The ensuing investigation brings the Wilby pair up against a seven-foot-tall mandrake, a gang of spectral parasites in the form of disembodied limbs, and a loquacious dragon with a discerning palate. They will need all their wits, spellcraft, and love for each other to survive this case.

Bancroft's nimbly narrated and sesquipedalian fantasy has an emotional core as solid as its detailed magical system. Fans of steampunk and other Victoriana will rejoice at this promise of an expansive world and a lovable couple with many adventures ahead of them. --Jaclyn Fulwood, blogger at Infinite Reads

Discover: This steampunkish fantasy-mystery novel features a strong leading couple, madcap humor, and witty narration.

Romance

The Takedown

by Carlie Walker

The Takedown, the first novel for adult readers by Carlie Walker, is as much a Christmas romance as it is an action-packed comedy. Sydney ran away from her life to join the CIA, never expecting to land right back in idyllic Maine where "[h]ip-tall, light-up candy canes line the sidewalks." Her new directive is to gather intel on the head of a crime family--who is engaged to her little sister. And if stopping the wedding, reconnecting with family, and staying undercover isn't enough, there's also Nick the bodyguard, who Sydney has to seduce for reasons of covert operations only--certainly not because he charms in his holiday sweater, sings Mariah Carey at karaoke, and is particular about his floss brand.

Walker captures moments of tense missions as easily as she does those of sweet family dynamics (Grandma Ruby roping Sydney into reprising her role as a donkey in the local Christmas pageant), along with the hilarity of two operatives conversing earnestly in a local Moose Lodge. As Sydney notes, "underneath it all I'm terrified. I'm just terrified that by wanting to be unknowable, I'll actually become unknowable, to everyone." This double-agent caper with a sizzling undercurrent of attraction culminates in a frenetic holiday dinner that feels both excessive and oddly relatable. The Takedown, delightfully comical with an emotional punch, will leave readers merry and grateful for their own family's holiday chaos--because at least they're not sitting at the Christmas dinner table trying to salvage a CIA operation, repair a sisterhood, and figure out whether the guy they're falling for can be trusted. --Kristen Coates, editor and freelance reviewer

Discover: The Takedown is a festive rom-com, featuring an undercover CIA agent, that delivers on action, laughs, and heartwarming moments.

Graphic Books

Glass Half Empty

by Rachael Smith

British comics artist Rachael Smith's third graphic memoir, Glass Half Empty, is a refreshingly candid account of her recovery from alcoholism after her father's death. Smith (Quarantine Comix) traces how her father's alcohol addiction affected her childhood. She remembers "writing to God to ask him to stop Daddy from drinking." From age 10 she attended Alateen, and her mother left instructions for what to do if she found her father passed out when she got home from school. Smith never knew if her father would be attentive or angry. "My sense of self-worth was always tangled up in how much I thought my dad loved me," she writes; in some of these panes, her adult self appears alongside her younger self, offering advice.

In the memoir's second half, she realizes alcohol has become problematic for her. She depicts her epiphany, "alcoholism is hereditary," as a literal bomb drop. Drinking is unhelpfully romanticized in writers, Smith remarks, whereas when she gives it up, she experiences greater creativity (and waking up without a hangover is nice). Abstinence is feasible for her, though moderation is not. Moving to a new town and seeing a therapist are positive developments.

Barky and Friendly, the imaginary canine pair from Smith's earlier work, appear here. Barky, the black dog, represents depression, and Friendly is an embodiment of self-compassion; they symbolize her mood swings and the opposing pulls of self-harm and healthy habits. The full-color illustrations are invigorating, and the memoir ends with a valuable list of resources. The self-deprecating humor and psychological understanding make this a brave accomplishment. --Rebecca Foster, freelance reviewer, proofreader, and blogger at Bookish Beck

Discover: Rachael Smith's third graphic memoir, which describes her experiences with tackling grief and alcoholism, candidly explores her past and present.

Food & Wine

Zingerman's Bakehouse Celebrate Every Day: A Year's Worth of Favorite Recipes for Festive Occasions, Big & Small

by Amy Emberling, Lindsay-Jean Hard, Lee Vedder, and Corynn Coscia, photos by E.E. Berger

Aspirational cooks and experienced chefs alike will delight in the edible abundance featured in Zingerman's Bakehouse Celebrate Every Day by Amy Emberling, Lindsay-Jean Hard, Lee Vedder, and Corynn Coscia. This second offering from the Ann Arbor, Mich.-based Zingerman's Bakehouse (Zingerman's Bakehouse) speaks to the seasons--Easter, Passover, Mother's Day, New Year's Eve, and beyond--with 80 recipes specially crafted for the joyful moments that elevate our days. The flavor and nutritional benefits of using freshly milled whole grains inspires such baked treats as Zinglish Muffins, a Memorial Day Blueberry Buckle, and Juneteenth Spider Bread, a delicious melding of New England flavors and Southern-style cornbread. The tasty selection of savory dishes includes a summer Chicken and Chorizo Paella perfect for the grill, with a stovetop version adapted for indoor cooking. The delightful 5 O'Clock Cheddar Ale Soup, inspired by Oktoberfest, and a hearty Beef and Guinness Stew embrace the shorter days and cooler weather. The authors encourage readers who don't see their particular holiday celebrated in the book to reach out via e-mail or Zingerman's website. After 30 years of remarkable growth, Zingerman's Bakehouse is still expanding its delicious repertoire of holiday recipes.

The authors capture the essence of each season's most beloved culinary traditions with stories and historical anecdotes highlighting the creative path that shaped Zingerman's Bakehouse into the cherished institution it is today, while the book's vibrant color photos by E.E. Berger are a testament to the emotional power of food. --Shahina Piyarali, reviewer

Discover: This tasty selection of savory dishes and classic baked treats from the popular Ann Arbor, Mich., bakery features 80 seasonal recipes for every joyful occasion.

Biography & Memoir

In the Form of a Question: The Joys and Rewards of a Curious Life

by Amy Schneider

"How Did You Get So Smart?" and "When Did You Know You Were Trans?" In her debut memoir, In the Form of a Question: The Joys and Rewards of a Curious Life, Amy Schneider uses questions as a framework for recounting a life dedicated to learning. Presenting more of an essay collection than a linear memoir, Schneider isn't interested in baring it all for readers--that is, behind-the-scenes Jeopardy! gossip or earth-shattering insights. Instead, she reveals the concerns of a normal life changed by sudden notoriety, and she does so with self-awareness and a hefty dose of humorous footnotes: "The Google auto-complete suggestions for searching my name can be depressing at times. Not that I'm going to stop Googling myself."

Schneider's journey to being the most successful woman to compete on Jeopardy! includes memories from a childhood during the heyday of the war on drugs to becoming a tarot-obsessed atheist as an adult. There's another layer to it all: the difficulty of writing a memoir as a trans author who came into her identity later in life. She describes her point of view as "the double-exposure way that trans people see the past, the way I can look back at a child who would say, 'I am definitely a boy,' and believe that child to be both wrong and right." With recognition of the privileges she's had as well as difficulties endured, Schneider's memoir fully commits to her own voice with unapologetic honesty. She grants grace to herself and others for what they know and don't know, emphasizing how personal evolution is always possible if someone, above all else, keeps learning. --Kristen Coates, editor and freelance reviewer

Discover: This debut memoir from the most successful woman to ever compete on Jeopardy! recounts a life of questions and answers with humor, honesty, and grace.

A.K.A. Lucy: The Dynamic and Determined Life of Lucille Ball

by Sarah Royal

In her introduction, Sarah Royal (Creative Cursing) forewarns the Queen of Comedy's fans that A.K.A. Lucy: The Dynamic and Determined Life of Lucille Ball isn't a straight-up biographical treatment. Instead, the book is "a vignette-style exploration of Lucy's life and career"--or, to put it another way, a biographically rich scrapbook-cum-fan journal offering much to mull over.

In the space around the photos, pull quotes, and themed lists, Royal tells the abridged story of Lucille Ball (1911-1989), the product of a rough-and-tumble childhood in Jamestown, N.Y. Ball was no instant sensation--I Love Lucy debuted in 1951, when she was 40--and Royal makes much of the actress's unsinkability during her many career setbacks on the road to the star-making TV smash.

A.K.A. Lucy may hold no fresh revelations, but what's here is expertly chosen. There's loads on Ball's work ethic, her overall menschiness, and the vexing question of whether she was a feminist. Although she rejected the label, Ball sure acted like a feminist: she was a glamour gal willing to look clownish--largely the province of male comedians in her day--and she created an indelible TV character whose defining attribute was her longing to be more than a housewife. A.K.A. Lucy would be a fine introduction for readers curious about TV's pioneering comedienne; those already besotted with Lucy will want to pull up a glass of Vitameatavegamin before tucking into delicious esoterica, like the chapter "Most Famous Episodes and Sketches of I Love Lucy, Dissected." --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

Discover: This biographically rich scrapbook-cum-fan journal dedicated to the pioneering I Love Lucy star offers much to mull over.

A Fine Line: Searching for Balance Among Mountains

by Graham Zimmerman

Graham Zimmerman felt strongly about climbing from his earliest experiences growing up in the Pacific Northwest, and by age 25 was an avid and accomplished international alpinist with his dreams focused on nothing else. But injury, loss, climate change, and a yearning for connection have forced him to consider how to combine his love for alpine ascents with social and environmental pursuits. A Fine Line: Searching for Balance Among Mountains is his thoughtful story of climbing communities in broader context, and his philosophies for a life well lived.

Not yet 40 at its writing, Zimmerman acknowledges "this is not a complete work," calling his book "a signpost along the way." It is still dense with lessons learned and offered, however. At just over 200 pages, A Fine Line reads quickly, many of its action sequences adrenaline-filled as Zimmerman recounts climbs with varying levels of success. It is also a neatly organized memoir, with the tensions between climbing and everything else appearing early. Following a major award, he experiences a significant fall, injury, and lengthy recovery, emphasizing the dangerous nature of his passion and his financial insecurity. The women he attempts to date react poorly to months-long absences on risky expeditions. Frequently climbing at high altitudes amid shrinking glaciers also alerts Zimmerman (trained in geology and glaciology) to the impacts of human-caused climate change.

As its subtitle forecasts, A Fine Line is about finding balance between an extreme sport in remote natural settings and "actual life in the lower regions." Obviously for fans of extreme outdoor sports, Zimmerman's debut is also recommended for readers seeking wisdom and balance in any pursuit. --Julia Kastner, librarian and blogger at pagesofjulia

Discover: Alpine climber Graham Zimmerman's memoir, dense with lessons learned and offered, recounts how he sought balance between his sport and the other elements of life.

Poetry

Gentle Chaos: Poems, Tales, and Magic

by Tyler Gaca

Tyler Gaca, who has attracted millions of followers online as Ghosthoney, celebrates self-discovery in Gentle Chaos, an ethereal collection of revelatory essays, expressive poems, and stunning artwork. "I've always been a sensitive child," Gaca, now 27, reveals. This fragility resonates within the tiny moments recalled from his childhood: searching under grocery store shelves for something magical, crying on his 10th birthday about growing old, becoming petrified by ghost hunters on television. "I was caught in this push and pull of being both fascinated and terrorized by horror." The macabre won, death and the unknown spurring Gaca into an adulthood marked by magic.

The pressed flowers, disembodied teeth, and snapshots of strangers immortalized in this collection carry a paranormal whimsy, as do his vulnerable musings: "I want to know how it feels to be a plant photosynthesizing" and "In a past life/ I was a garden snake./ That glowed/ like a violent beacon." He talks openly of being late to accept his queer identity yet always wanting love; of losing his artistic drive and the spark that brought it back; of early days with his husband, JiaHao. Stories behind several of his TikTok characters reveal how his "imagination run[s] rampant" to produce off-putting and gently mysterious creations. Threading together the tenderly meandering pieces--a painting of a Moon Pie; a full spread of his shorn hair; a handwritten recipe for raw apple cake from his great-grandmother; a "guide to dressing like a love-stricken Victorian dandy"--is a patient joy and willingness to dream. Gentle Chaos is sure to inspire reflection and cultivate an adventurous spirit in readers. --Samantha Zaboski, freelance editor and reviewer

Discover: This nurturing compilation of vulnerable thoughts, poetry, and art by Tyler Gaca, known online as Ghosthoney, invites readers to embrace the magic in everyday life.

Now in Paperback

The Winners

by Fredrik Backman

The story "starts right here and ends in less than two weeks, and how much can happen in two hockey towns during that time? Not much, obviously. Only everything." Fredrik Backman (Britt-Marie Was Here; A Man Called Ove) opens The Winners, translated from the Swedish by Neil Smith, with a tease. This, the final novel of his Beartown trilogy, is a big-hearted, epic novel, bouncing between hope and tragedy as smoothly as a puck flying down the rink.

Readers new to Beartown and Hed, the adjacent Swedish towns and hockey rivals of Backman's Beartown and Us Against You, will quickly pick up their culture and bitter history. Backman's omniscient narrator inserts foreshadowing: "Naive dreams are love's last line of defense," he warns on page one. When he writes that "all that holds us together in the forest is our stories," readers are reminded, as the beloved proprietor of the Bearskin bar says, that "everything and everyone is connected around here, whether they like it or not."

The "two weeks" of the novel includes backstories: the unforgettable violent act in the trilogy's second novel; ongoing shady political and business dealings that threaten one town's team and an iconic coach's reputation; deep love between husbands and wives, parents and children; and friendships that span decades. Opening with a fierce storm that finds two women, one from each town, overcoming daunting odds to deliver a baby in the forest, and ending with the introduction of a skater who one day "will make us feel like winners again," Backman brings his saga to an often brutal but ultimately heartwarming and hopeful conclusion. --Cheryl McKeon, Book House of Stuyvesant Plaza, Albany, N.Y.

Discover: The epic conclusion to the Beartown trilogy will satisfy even those new to Beartown and Hed, towns deep in the Swedish forest whose citizens are obsessed with their rival hockey teams.

The Singularities

by John Banville

Fans of Irish novelist John Banville (Snow; Holy Orders, writing as Benjamin Black; Ancient Light) will recognize many of the characters, even one now using an assumed name, in The Singularities. They include Adam Godley Jr., son of the famous mathematician Adam Godley Sr., and young Adam's wife, Helen. Also returning is Freddie Montgomery, who committed murder in The Book of Evidence and returned in two of Banville's subsequent works. This time, intent on "total transformation," Montgomery calls himself Felix Mordaunt. He has been released from prison after "some twenty years of a mandatory life sentence" and has returned to Coolgrange, his childhood estate. Only now it's called Arden House, Godley's family lives there, and Mordaunt returns to work as the family's driver. One of his fares is William Jaybey, whom the younger Adam has hired to write a biography of his father, celebrated for having developed something called the Brahma theory. But Jaybey has a long-held vendetta against the deceased Godley and plans to get revenge by "chipping away with mallet and chisel" at his reputation.

Intrigues follow and secrets are revealed in this exceptional work. Like many Banville novels, this one is heavier on descriptions than plot, but what exquisite descriptions: a gate at Arden House has "rust reminiscent of a dusting of roughly ground cinnamon" and gives "the impression of leaning dejectedly over itself, limp and blear-eyed, defeated by the years." The Singularities is like a carriage ride along a country lane: it proceeds slowly, affording ample time to admire the scenery. --Michael Magras, freelance book reviewer

Discover: Characters from past novels return in John Banville's intriguing story about a released prisoner, a country house, a mysterious family, and well-kept secrets.

One Hundred Saturdays: Stella Levi and the Search for a Lost World

by Michael Frank, illus. by Maira Kalman

Michael Frank's One Hundred Saturdays--a Shelf Awareness Best Book of 2022--is the emotionally stunning biography of Stella Levi, one of the last Jewish survivors of the Greek island of Rhodes. Levi's beloved Juderia, Rhodes's Jewish quarter, spanned about "ten, twelve square blocks in all," cobblestoned streets and courtyards smelling of "jasmine and rosemary, lavender and roses and rue."

At one of their first meetings--eventually becoming 100 Saturdays over the course of six years, Frank asks Levi to share her life story. "Possibly," she says. "But not the camps.... I don't want to be that person." Levi recalls her youth: weddings, Yom Kippur, Passover, the frisson of first love. The image of her packing a suitcase at age 14 to be ready for university echoes throughout the book. Levi eventually describes her deportation to Auschwitz, among the 1,650 Jews collected from Rhodes, and her survival of five different camps.

Maira Kalman's gouache paintings in burgundies, yellows, blues and greens depict moments both small (wearing an outfit her sister sent from "Ah-merica") and life-altering ("The window [that] was the last thing Stella saw that connected her to the Juderia").

This biography, winner of the Jewish Book Council’s Natan Notable Book Award, pins to the page a lost world preserved in these carefully captured memories. --Samantha Zaboski, freelance editor and reviewer

Discover: This emotionally stunning biography relates the story of one of the last Jewish survivors of the Greek island of Rhodes.

Live Wire: Long-Winded Short Stories

by Kelly Ripa

Live Wire: Long-Winded Short Stories, the first book from Emmy Award-winning actress and talk show host Kelly Ripa, is not a memoir. Instead, it's an enjoyable and brightly written collection of personal essays that allows her to cherry-pick the highs and lows of her life. At age 20, she joined the daytime soap opera All My Children, where she met and married her costar Mark Consuelos. She began co-hosting the morning talk show Live with Regis and Kelly in 2001. When Regis Philbin retired a decade later, she became the head of the show. "[P]laying yourself on television is the hardest role I've ever had," writes Ripa, "especially when I started before I even knew who I really was."

Readers will find a saltier Ripa on these pages than on her morning show--complete with f-bombs and sexually straightforward tales. (One account begins with her and Mark's first attempt at sex after she gave birth to their first child and ends with a trip to the hospital.) Fans will love the nuggets of advice sprinkled throughout her essays, including "I think it's important never to fake illness or orgasm." Essay topics include Botox and plastic surgery ("My neck was aging in dog years compared to my face"); the transition to empty-nest parenthood; when Mark broke up with her five days before their wedding; and her relationship with tabloids. She writes gingerly of her relationship with the curmudgeonly Philbin, realizing belatedly that he may not have thought they were as close as she thought they were.

Live Wire is a splendid, fast-moving autobiographical essay collection with polished bon mots and real heart. --Kevin Howell, independent reviewer and marketing consultant

Discover: Ripa's first book, Live Wire, is an entertaining, fast-moving, thoughtful and polished collection of autobiographical essays that lets her be racier than morning TV allows.

Children's & Young Adult

There Was a Party for Langston

by Jason Reynolds, illus. by Jerome Pumphrey and Jarrett Pumphrey

Three creators at the toe-tapping tip-toppest of their game deliver a soulful tribute to a beloved poet, essayist, and cultural leader in the melodic There Was a Party for Langston, written by Jason Reynolds (Stuntboy, in the Meantime; Ghost) and illustrated by siblings Jerome Pumphrey and Jarrett Pumphrey (The Old Truck).

The grand opening of the Schomburg Center's auditorium inspires a "jam in Harlem to celebrate the word-making man--Langston, the king of letters." Langston Hughes made words dance on the page and, on this February 1991 evening, literary luminaries boogie the night away in his honor. "All the best word makers were there," but two guests take center stage: Hughes's "word-children," Maya Angelou and Amiri Baraka, who "danced, like the best words do, together."

The Pumphrey brothers use their signature stamping technique to create magnificent results. Sunny yellows and matte, muted browns and blues evoke a bygone era. A dizzying array of page designs that incorporate plenty of white space maximize both the landscape format of the open book, and the portrait format of each individual page. The artwork incorporates the musicality and playfulness of Reynolds's exuberant language while bolstering Hughes's impact with subtle design elements.

Former National Ambassador for Young People's Literature Reynolds makes his picture book debut in this joyful and rhythmic triumph. The text is reverential yet jolly; "Langston's language-laughter tickle[s]" readers without ever losing focus on Hughes's profound literary impact. This boisterous read-aloud is equal parts endearing homage and history lesson about a literary giant, and it is truly something to celebrate. --Kit Ballenger, youth librarian, Help Your Shelf

Discover: A notable creative team joins forces in a melodic picture book that pays joyous and rhythmic homage to a literary icon.

Before the Devil Knows You're Here

by Autumn Krause

Autumn Krause's sophomore YA novel is a dark, lush, original folktale told from two perspectives: Mexican American teen Catalina, a girl searching for The Man of Sap, and John, who through his misfortune becomes the Man of Sap.

In a broken-down shack in early-19th-century Wisconsin, Catalina's father is killed, and her brother, Jose Luis, is kidnapped by the Man of Sap, a man/tree creature who, "sowing seeds of sin... grows apples of ash." Catalina's father had told her stories about the Man of Sap and his deadly apples since she was a small child, devastated by her mother's mysterious death. Now 17, Catalina is determined to rescue Jose Luis, her only surviving family member. In her travels, she meets and joins forces with Paul, a sickly lumberjack who is also seeking the Man of Sap. As they search, Catalina and Paul are both helped and attacked by birds, encounter beings of myth and legend, and find in each other a kindred soul. Woven alongside Catalina's third-person odyssey is the first-person tale of John, an apple farmer whose dream of a thriving orchard led him to sign a deal with the devil.

Krause (A Dress for the Wicked) invents here an original folktale that is part Johnny Appleseed, part "The Devil and Daniel Webster," and uses dual narratives to tell two distinct, engrossing stories that intertwine in unexpected ways. Her prose is descriptive and delicate, her mythical world populated with creatures both intriguing and terrifying. Krause delivers an excellently creepy legend perfect for Halloween reading. --Deanna Meyerhoff, reviewer

Discover: A Mexican American teen must embark on a frightening journey to reunite her family in this breathtaking, haunting original folktale.

Nell of Gumbling: My Extremely Normal Fairy-Tale Life

by Emma Steinkellner

An "ordinary" tween living in an extraordinary place finds out that happily-ever-after can take many forms in Nell of Gumbling, a colorful and enchanting fantasy graphic novel from Emma Steinkellner (The Okay Witch).

Nell Starkeeper is a 12-year-old artist who lives in the town of Gumbling with her two star-farmer dads and her younger siblings, Rib and Schmitty. Gumbling (formerly "the Most Precious Kingdom of Gumbling") is a magical town with a rich history and culture, of which its residents (including Yabulga, the town Witch) are proud. Nell, who is once again trying to maintain a journal, is eagerly awaiting her teacher's announcement of class apprenticeships--she is certain she will be apprenticed to Wiz Bravo, "the town's most famous artist." To her immense disappointment, Nell is instead sent to assist Mrs. Birdneck, the Town Lorekeeper. As Nell struggles to figure out how to shine in this assignment, she also tries to thwart two strangers with suspicious intentions.

Steinkeller delivers a delightful graphic novel for young readers that effortlessly features diverse characters living in an uncommon yet "normal-ish" fantasy world. The situations Nell describes in her journal effectively illustrate how she is struggling with changing friendships, onerous family obligations, and the difficult task of growing up. The author consistently plays with the format of the book, switching between pages of text with spot art, graphic novel panels, scrapbooking, and double-page illustrations, making for an interactive and easy reading experience. Nell of Gumbling is a perfect introduction to both graphic novels and the fantasy genre. --Shannan L. Hicks, freelance writer and librarian

Discover: An "ordinary" tween living in an extraordinary place finds out that happily-ever-after can take many forms in this enchanting and colorful graphic novel.

Wrecker

by Carl Hiaasen

Set in Key West, Fla., during Covid-19, Wrecker by Carl Hiaasen (Hoot; Chomp) is an action-packed and endlessly funny middle-grade mystery that follows Wrecker, a Bahamian-descended sailor turned accidental smuggler.

Fifteen-year-old Valdez Jones VIII, aka Wrecker, is returning from a fishing trip when he witnesses an expensive speedboat run aground. When he sails over to help, the captain of the vessel, "Silver Mustache," behaves suspiciously, offering Wrecker a beer can with a wad of cash inside. "Yo," he says, "just remember: you never saw us." Wrecker takes the money and tries to forget about the strange experience. Then, while Wrecker's working his odd job cleaning iguana droppings off a gravestone, Silver Mustache approaches and asks him to keep an eye on the crypt of a recently deceased friend. Wrecker reluctantly agrees, but senses that something fishy is afoot when black-coated thugs begin standing guard at the crypt and threatening passersby. After a chance encounter with a sunken speedboat--and its potentially illegal contents--Wrecker hatches a plan to thwart Silver Mustache's clandestine operations.

Wrecker is a charming and adventurous novel for young readers from a great contemporary satirist. Hiaasen's palpable descriptions of setting, trademark sense of humor, and masterful use of cliffhangers keep readers happily engrossed. And the work goes beyond pure enjoyment--Hiaasen engages with themes of racism, environmental exploitation, and public health in a way that is simultaneously poignant and lighthearted. A thrilling story with memorable characters and a spirited attitude, Wrecker is sure to delight longtime Hiaasen fans and lovers of mysteries alike. --Cade Williams, freelance writer.

Discover: This action-packed and endlessly funny middle-grade mystery follows 15-year-old Wrecker, a Bahamian-descended sailor turned accidental smuggler.

The Siren, the Song, and the Spy

by Maggie Tokuda-Hall

The Siren, the Song, and the Spy is a welcome companion to Maggie Tokuda-Hall's ethereal The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea, and brings to a head the long-simmering conflict between the Resistance and the greedy Nipran Empire.

Imperial operative Genevieve has not died. The pirate ship Dove exploded while under attack but, by the grace of the Sea, Genevieve has landed safely on the Red Shore. She was trained by "the Emperor's greatest spy," but in her weakened state she's taken prisoner by two warriors, brother and sister Koa and Kaia, whose mother rules the Wariuta people. Black-haired, sunburnt-pink Genevieve can speak many languages so, despite Kaia's hatred for her, Genevieve is considered useful. When Imperial Commander Callum comes with a proposal for peaceful occupation, Genevieve encourages the Wariuta to accept. But Callum's soldiers massacre the islanders, and Genevieve must reckon with her complicity in the Empire's brutal agenda. Though the various factions of this splintered world try to come together through shared hatred of the Emperor, it might take a mythical First Dragon from the deepest depths of the Sea to turn the tide.

Tokuda-Hall writes elegantly and uses numerous points of view, such as Genevieve's childhood voice (when she was called Thistle), and those of Koa, Kaia, and even the Sea. Magical prose flows smoothly and brings a sense of enchantment to the story. This strong offering about imperialist aggressions, rebels, and reprisal should effortlessly sweep readers into its realms as it makes a compelling plea for pacifism. --Lynn Becker, reviewer, blogger, and children's book author

Discover: This elegant companion to Maggie Tokuda-Hall's ethereal The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea brings the long-simmering conflict between the Resistance and the greedy Nipran Empire to a head.

In the Media

What to Watch

From Page to (Small) Screen

Authors use words to paint a scene on the page; filmmakers use lighting and costumes and color to create cinematic moments. Two beloved books will soon come to television: Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus (Doubleday, $29) is the basis for an eight-part series for Apple TV+, directed by Sarah Adina Smith. The first two episodes premiere October 13, and the rest drop through November 24. All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr (Scribner, paperback $18.99), forms the foundation of a four-part Netflix limited series, directed by Shawn Levy, premiering November 2.

Authors use words to paint a scene on the page; filmmakers use lighting and costumes and color to create cinematic moments. Two beloved books will soon come to television: Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus (Doubleday, $29) is the basis for an eight-part series for Apple TV+, directed by Sarah Adina Smith. The first two episodes premiere October 13, and the rest drop through November 24. All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr (Scribner, paperback $18.99), forms the foundation of a four-part Netflix limited series, directed by Shawn Levy, premiering November 2.

The opening episode of Lessons in Chemistry starts as the book does, in the sense that it reveals Elizabeth Zott (Brie Larson) as the star of the TV series Supper at Six. But television affords viewers the chance to fully take in Zott's glamour as she steps out of her car at the studio to greet her line of fans, dressed in an unmistakable early-1960s palette of olive greens, creamy yellows, powder blues, and rosy reds. Next, we travel back seven years, to when Zott was intent and masterful in her work at a chemistry lab, but where her beauty and gender overpowered her intelligence in the perception of her coworkers. Everyone but Calvin Evans (Lewis Pullman), that is, who recognizes her brilliance and invites her to be his lab partner, as a peer.

Another smart move casts Aja Naomi King as Zott's neighbor Harriet Sloane. In Eisenberg's version, Sloane, like Zott, has had her career thwarted: Sloane dropped out of law school when she became pregnant so her husband could continue his medical residency. But she puts her talent and intelligence to work leading the charge to protest plans to run a freeway through their predominantly Black neighborhood in Commons, Calif., just outside Los Angeles. The way that first Evans, then Zott, connect with the Sloane family develops organically and credibly--not without missteps--and King's performance is a standout, especially as she navigates her husband's return from serving with the medical corps in Korea.

While the Korean War is a specter in the background of Lessons in Chemistry, World War II envelops All the Light We Cannot See. A background of shadows and darkness, muted browns, and midnight blues shrouds Marie-Laur LeBlanc as she reads in Braille 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea over the radio. With barely enough illumination for viewers to see her face, we get a hint of what it must be like for Marie-Laur, blind from age six. Director Levy cast his net wide in searching for someone with the lived experience to play Marie-Laur, and his extraordinary discovery was Aria Mia Loberti, a Fulbright scholar, academic, and advocate for the blind, making her debut as an actress in this series.

While the Korean War is a specter in the background of Lessons in Chemistry, World War II envelops All the Light We Cannot See. A background of shadows and darkness, muted browns, and midnight blues shrouds Marie-Laur LeBlanc as she reads in Braille 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea over the radio. With barely enough illumination for viewers to see her face, we get a hint of what it must be like for Marie-Laur, blind from age six. Director Levy cast his net wide in searching for someone with the lived experience to play Marie-Laur, and his extraordinary discovery was Aria Mia Loberti, a Fulbright scholar, academic, and advocate for the blind, making her debut as an actress in this series.

Steven Knight, who adapted the teleplay from Doerr's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, smoothly works in the relevant details: the way Marie-Laur's father (Mark Ruffalo) taught his blind daughter to navigate the streets of Paris (using an exquisite miniature wooden model of the city, set out on a table at her waist height); the storied diamond Sea of Flames, the other precious treasure he must protect, through his work at Paris's Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle--a gem revealed to be coveted by a Nazi jeweler--and the leaflets dropped by U.S. warplanes, warning the citizens of Saint-Malo, France, to evacuate. We also learn from Marie-Laur's uncle Etienne (Hugh Laurie) that her radio broadcasts carry more than Verne's words; they are messages to the Resistance.

Book Candy

Book Candy

"The best hotels--and hotel bars--in espionage fiction" were featured in CrimeReads.

---

"Eat like an Ancient Greek philosopher" with Deipnosophistae (The Learned Banqueters), describing dinner parties Athenaeus attended in Rome. (via Gastro Obscura)

---

Messy Nessy explored the first Birth Control Handbook, written by a group of teenagers in 1968.

---

Mental Floss remembered "when Ernest Hemingway walked away from two plane crashes just hours apart."

Death Valley

by Melissa Broder

In Death Valley, Melissa Broder (Milk Fed; The Pisces) brilliantly dissects the intersections of grief, loss, and depression (heavy topics, all approached with an unexpected sense of humor) through her protagonist, an author ostensibly seeking inspiration for her next novel. The unnamed woman flees to a desert motel in hopes of finding not just a story, but an escape from her own life--only to learn that escape in the desert can prove more dangerous than she ever might have imagined.

Pulling into a Best Western well outside of Los Angeles, the woman reflects on the weight of the emptiness she carries around inside. In desperation, she reminds herself that her "doominess isn't baseless," but borne of a life in L.A. that feels unmanageable (as though that reminder might somehow make it feel more manageable). "There's something to be said for manufacturing a crisis (a crisis can be simpler than just living)," she reflects, though she has no need to manufacture crises when life has offered her plenty of them. Her father has been in and out of intensive-care units and on the brink of death for five months, following a tragic accident, alternating between prolonged bouts of unconsciousness and surprising revivals. Her husband has spent nine long years with a debilitating and seemingly undiagnosable illness that leaves him bedridden for months on end. It seems her whole life has been about taking on other people's feelings as hers to manage, as the eldest daughter of a depressed father and a mother unwilling to acknowledge--let alone speak about--emotions of any sort: "I came to escape a feeling--an attempt that's already going poorly, because unfortunately I've brought myself with me, and I see, as the last pink light creeps out to infinity, that I am still the kind of person who makes another person's coma all about me."

The Best Western receptionist encourages the woman to order the blueberry muffin for breakfast (and definitely not the breakfast sandwich), and then to visit a local hiking trail. There, she finds huge cactuses--one so enormous she believes she can enter its cavity through a splice in its side, and so much larger-than-life that, once inside, she sees within it her father as a guitar-playing boy in his prime. She is entirely sober (refusing even cough syrup after struggling with addiction and recovery), and the image is clear enough to present as reality. "Does having visions inside a cactus count as a relapse?" she ponders to the sand and rocks. With the discovery of the revelatory cactus--which the staff of the Best Western insist cannot and does not exist--Death Valley slips out of reality and into something akin to a fever dream, with the boundaries between what is real and what is imagined (and what, perhaps, is a mirage) ever blurring along the way.

Self-described as a sober woman of many years, struggling with depression, the heroine is overly prone to "trying to solve a problem, the problem of me and my mood, rather than just experiencing it. But how do you just experience things?" This question, so pivotal to her desert flight to begin with, becomes moot when she takes a wrong turn on the trail, and finds herself thoroughly and completely lost in the wilderness: alone, unprepared, with limited water and just a bag of motel to-go breakfast for sustenance. Her only conversation partners are the rocks she's found and named (and granted personalities: The Egg, Grey, Door, etc.). And thus, her experience is reduced to just that: an experience, devoid of emotion, empty of the things that used to scare her. Instead of obsessing about "doom, mood, magic daughter, anticipatory grief, husband illness, bed-vortex, Montezuma Cypress, not good enough, the sky," she is--and must be--focused on survival: sips of water, shade in the daytime, warmth at nightfall, the limited battery in her phone, and continued lack of signal to call for help.

Within this desperate (if unanticipated) desire to simply survive, she finds a kind of presence she's not known before, one brought to life in Broder's elegant descriptions of the unexpectedly beautiful details of desert wilderness that appears barren from afar: "The crystallized beavertails. The rising sandstone wall and the steepening drop. Pistachio moss, chartreuse moss. Yellow flowers. Eroded ghost emoji log." (The latter representative of her enduring sense of humor, even in the darkest of moments.)

Ultimately, Death Valley is a story centered on survival: what it means to survive in a landscape not primed for human thriving, be it the literal desert or the more emotional world of anticipatory grief and loss, and what it means to survive a deep, unfathomable sense of loneliness while craving aloneness with a kind of wild desperation. In Broder's skilled hands, a story that could read as hopeless and desperate proves heartfelt and tender, moving seamlessly between the surreal and the all-too-real and back again. At times disorienting, at times familiar, and beautiful throughout, Death Valley is a smart, darkly comedic novel that reimagines the experience of grief in inspired and unexpected ways. --Kerry McHugh

Seeking as a Form of Escape

An Interview With Melissa Broder

|

|

| (photo: Ryan Pfluger) | |

Melissa Broder is the author of the novels Milk Fed and The Pisces; the essay collection So Sad Today; and five poetry collections, including Superdoom and Last Sext. She has written for the New York Times, Elle.com, VICE, Vogue Italia, and New York Magazine's "The Cut." A Pushcart Prize-winning poet, Broder has published poems in Poetry, the Iowa Review, Guernica, and Fence, among others. She lives in Los Angeles. Her third novel, the darkly comic Death Valley, about a woman writer who goes to the desert to escape the tragic developments in her life, will be published by Scribner on October 24.

This book is, in a word, unique! (I loved it!) Where did this project originate for you?

In 2020, my father was in a car accident that put him in the ICU for six months before he died. He was on the East Coast, I was on the West, and no one was allowed in to see him for the first months because of Covid. I was powerless--and I needed to escape a feeling. But you can't escape a feeling because a feeling is inside you. Still, I tried, driving back and forth through the desert between my home in L.A. and my sister's in Las Vegas. I was driving through Baker, Calif., home of the world's largest thermometer, when the first two sentences of the novel came to me.

Does your work start with a kernel and evolve as you write? Or did you outline and plan this book in some way?

Always a kernel first: a magic cactus; a merman; two women in love--one zaftig, one eating-disordered--and a pile of frozen yogurt. Then comes an outline. But my outlines are like the ship of Theseus. Piece by piece, they change as I move through the draft. By the end, it's a different ship. And yet the same ship.

This book's outline changed when I did a "desert recon" trip midway through the first draft. I took a little hike in a touristy area of Death Valley where nobody gets lost. Well, I got lost. My phone had no service. I had no water. Only Coke Zero like a fool. I was crying. "How long have I been out here?" Half an hour. I panicked after half an hour of being lost. And in my panic, I scraped myself up getting back.

But once I made it back, I was very pleased despite my injuries. Now I knew what had to happen. My protagonist was going to get lost in the desert. And she would get lost for longer than half an hour.

Can you talk a bit about the parallels you see between grief and wilderness survival? That connection feels very present in the novel in imaginative and unexpected ways.

Grief is so physical. It's shockingly physical. The heaviness, the ache, the exhaustion. As I write this, it's the two-year anniversary of my dad's passing, and the aftermath of a friend's death by suicide, and I'm wrecked. And I want to not be wrecked. I'm frightened by the wreckedness. But wanting to not be wrecked, or judging ourselves for being wrecked, doesn't make us less wrecked. Similarly, wanting to not be lost in the desert doesn't make us any less lost. Grief is a force. Nature is a force. In both cases--grief and desert lostness--we keep walking. But we can't see, and we're scared, and we wonder: Will this ever end? Will I be okay? Will I survive this?

The main character here is fleeing: her life, her dying father, her ailing husband, her grief and her depression. But in the process of fleeing, she also seems to be seeking something. Do you see fleeing from and seeking something to be related to one another? Two sides of the same coin?

In my experience, fleeing and seeking can be two sides of the same coin, because seeking is often a form of escape: seeking to be other than we are; seeking for reality to be different than it is; seeking refuge. Also, both actions always lead me back to a fundamental, if annoying truth, which is that acceptance is the only answer.

She is also deeply alone, and yet very linked to others, both in person (the hotel reception staff people) and electronically (her sister, mother, father, ICU nurses). What might you say about that tension between solitude and interconnectedness, especially as it relates to depression and sadness?

It can be challenging when a person has depression and anxiety--or is in a state of grief, which resembles many of the symptoms of depression and anxiety--to be with people. There's the fear of judgment, the heightened nervous sensitivity, the constant checking of one's mood against one's performance. But at the same time, depression feeds on isolation, and genuine human connection is healing. So, the question is: What do we do when we need people but are kind of scared to be with people? I'm still figuring this one out.

Did the pandemic in any way shape the role of technological communication in this novel?

Absolutely. The first two months my father was in the ICU, when we weren't allowed in, my sister and I FaceTimed with him every single day. Sometimes he was unconscious, and the nurse put the phone on his pillow, and we just talked to him. Sometimes he was fully lucid and cracking dry jokes. The day before he died, I was there with him, and I made sure to FaceTime in my sister. He really felt like she was in the room, too. When I was leaving, he said, "Melissa, take your sister with you."

I loved the ways that the visions she sees in the cactus are directly connected to old family photographs, and the stories told about them across the years. How do you see photographic moments shaping memory and recollection, in this novel and/or in your own experience?

I'm not a very visual person. My melatonin-dreams are the most imagistic I get. In fact, I often create word banks of nouns--lists and lists of juicy nouns scattered all over my house--and weave them into my texts when I'm editing. With this book, I took a lot of gorgeous nouns from vintage copies of Desert magazine that I bought on eBay, just to make sure the text was steeped in that specificity of imagery. So, I don't personally use photographs when I write. But I grounded a lot of the fantastical elements of the novel in photographs, Reddit posts, and images that the protagonist had seen, because I felt it was important to "earn" the fantastical, archetypal elements of the book. This comes from having a poetry background, I think, in which a teacher once said to me, "You have to teach the reader how to live in the world of the poem and then you can do whatever you want." It's like Chekhov's gun but in reverse. Chekhov's cactus.

While I've not spent time in the desert myself, the concept of a mirage is closely linked in desert stories. Do you consider Death Valley to be a "mirage novel," to make up a new genre of sorts?

I think the line between reality and mirage is so blurry to begin with, which is why I'm always confused by the term "unreliable narrator." Like, aren't we all unreliable narrators? People often ask me if the merman in my novel The Pisces was "real" and I don't know how to respond, other than to say, "He's real to the protagonist." But I do like the term "mirage novel!" Now I'm thinking of a number of mirage novels, which, although not set in the desert, weave the subjectivity of the human psyche into physical wilderness: The Ice Palace by Tarjei Vesaas. Down Below by Leonora Carrington. Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain... now that's a mirage novel! --Kerry McHugh

Great Reads

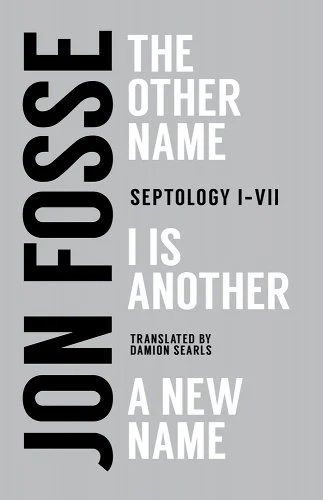

Rediscover: Jon Fosse

The 2023 Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded this week to Norwegian author Jon Fosse for his "innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable," the Swedish Academy announced. Fosse has written more than 40 plays, novels, short stories, children's books, poetry, and essays. The Academy said that Fosse's "magnum opus in prose" is Septology, which he completed in 2021 and was published in several volumes. A New Name: Septology VI-VII was a finalist last year for the National Book Awards, the National Book Critics Circle Awards, and the International Booker Prize.

The 2023 Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded this week to Norwegian author Jon Fosse for his "innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable," the Swedish Academy announced. Fosse has written more than 40 plays, novels, short stories, children's books, poetry, and essays. The Academy said that Fosse's "magnum opus in prose" is Septology, which he completed in 2021 and was published in several volumes. A New Name: Septology VI-VII was a finalist last year for the National Book Awards, the National Book Critics Circle Awards, and the International Booker Prize.

Fosse's debut novel Red, Black (1983) is, the Academy said, "as rebellious as it was emotionally raw, broached the theme of suicide and, in many ways, set the tone for his later work." Another key work is Trilogy (2016), "a cruel saga of love and violence with strong Biblical allusions, [which] is set in the barren coastal landscape where almost all of Fosse's fiction takes place." It was published in the U.S. by Dalkey Archive Press.

"In common with his great precursor in Nynorsk literature Tarjei Vesaas, Fosse combines strong local ties, both linguistic and geographic, with modernist artistic techniques," the Academy said. "While Fosse shares the negative outlook of his predecessors, his particular gnostic vision cannot be said to result in a nihilistic contempt of the world. Indeed, there is great warmth and humour in his work, and a naïve vulnerability to his stark images of human experience."

"Extending to 1,250 pages, [Septology] is written in the form of a monologue in which an elderly artist speaks to himself as another person. The work progresses seemingly endlessly and without sentence breaks, but is formally held together by repetitions, recurring themes and a fixed time span of seven days. Each of its parts opens with the same phrase and concludes with the same prayer to God." It was published in the U.S. by Transit Books. They will also publish Fosse's A Shining later this month.

Read what writers are saying about their upcoming titles