There is a celebration day for almost anything. In May, we have Mother Goose Day, Save the Rhino Day, Lost Sock Memorial Day (but no Dryer Day) and, of course, Cinco de Mayo and Memorial Day. Less familiar is National Nurses Day, May 6. First observed in 1954, it marks the beginning of National Nurses Week, which ends May 12, the birthday of Florence Nightingale.

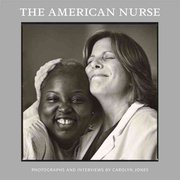

If you know a nurse, like a nurse or have given thanks to a nurse, Welcome Books has the perfect book for you: The American Nurse: Photographs and Interviews by Carolyn Jones ($60). Jones, a photographer and filmmaker tells the stories of 75 women and men in "an ode, a celebration, a vote of gratitude" to extraordinary people. Her book and website are the first steps in The American Nurse Project; next is a documentary film following six nurses around the nation, like Jason Short, a former mechanic and truck driver who now works in the remote hollows of eastern Kentucky, and Tonia Faust, who directs the hospice program at Angola State Penitentiary in Louisiana.

If you know a nurse, like a nurse or have given thanks to a nurse, Welcome Books has the perfect book for you: The American Nurse: Photographs and Interviews by Carolyn Jones ($60). Jones, a photographer and filmmaker tells the stories of 75 women and men in "an ode, a celebration, a vote of gratitude" to extraordinary people. Her book and website are the first steps in The American Nurse Project; next is a documentary film following six nurses around the nation, like Jason Short, a former mechanic and truck driver who now works in the remote hollows of eastern Kentucky, and Tonia Faust, who directs the hospice program at Angola State Penitentiary in Louisiana.

The book is oversized, with a portrait on one page, the nurse's story on the facing page. Stories like that of Heather Cowan, who got her RN when she was 50 and now works in a hospice, where, she says, intimacy and honesty call forth the best parts of herself. Venus Anderson is a life-flight nurse whose stance of no emotional connection with trauma patients changed after her father died on an emergency flight--connection is no longer a waste of time to her. Mohamed Yasin, a nurse manager, mentors new nurses, explaining it's not the glass of water that they give, it's how they give it "that will make it tasty."

Jones says, "Nurses have seen things that none of us can imagine. I'm in awe... they are a special breed." With her book, we can share in her awe and be grateful. --Marilyn Dahl, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers

Equilateral

by Ken Kalfus

After two collections of short stories and two novels (including the National Book Award-nominated A Disorder Peculiar to the Country), Ken Kalfus's Equilateral takes on science fiction, but with a distinctly 21st-century twist: think Jules Verne meets Ray Bradbury meets China Miéville.

In the Great Sand Sea of western Egypt in the 1890s, a sprawling encampment occupies thousands of square miles, as hundreds of thousands of fellahin excavate "exceedingly wide roadways into which a lining of pitch is being laid." This is Professor Sanford Thayer's empire, where his "famously acute vision" is to be realized--a "pure, uncompromised expression of human intelligence." His creation, a massive equilateral triangle, will be set afire when the "fierce, unquenchable ember" of the planet Mars is at its closest point to the earth, so the Earth can attain fiery contact with the Martians.

Despite the thousands involved in this project, the actual cast of characters in Equilateral is small--four--and the book itself slight, compact in a good way. A somewhat sly omniscient narrator seems positioned in the audience, watching and commenting as if this were a stage play. Besides Thayer, there are Miss Keaton, his tireless, devoted assistant; Bint, a Bedouin servant girl; and Wilson Ballard, the chief engineer and slave taskmaster. In a desert setting "as empty and cold as interplanetary space," Kalfus slowly unfolds a subtle morality play about the cost of scientific arrogance, intellectual hubris and imperiousness toward others--and the period illustrations contribute greatly to the book's echoes of a 19th-century scientific treatise. --Tom Lavoie, former publisher

Discover: A thoughtful, wisely rendered modern science fiction pastiche with just the right dash of an Ibsen play.

The View from Penthouse B

by Elinor Lipman

Elinor Lipman (The Inn at Lake Devine) can always be counted on to make you empathize with her characters, whether you're chuckling or looking askance at them.

Two 50-something sisters have almost simultaneous downturns in their well-planned lives. Margo's husband, a fertility doctor, is indicted and found guilty of being a bit too enthusiastic about making his patients pregnant. (One might say that his participation is complete.) Margo divorces Charles instantly, gets half his money and buys a gorgeous penthouse in the West Village. She then invests the rest with Bernie Madoff--and we all know what happens then.

Her sister, Gwen-Laura, wakes up one morning--but her husband doesn't. Gwen is bereft beyond imagining; she is still crying two years after the fact and shows no sign of letting up or moving on. Their younger sister, Betsy, takes them to lunch and suggests that they move in together. They mull it over for about 10 seconds and call for the moving van.

Margo finds Anthony, a young, handsome, gay cupcake maker, and the household is complete. As these three strategize about ways to earn money, Charles is paroled and moves into a tacky little studio on the first floor--with no stove. This necessitates frequent meals with the Penthouse trio. You might imagine what happens next, but Lipman has a few surprises in store. --Valerie Ryan, Cannon Beach Book Company, Ore.

Discover: Two sisters who have recently experienced losses (though under much different circumstances) share a penthouse and work on moving on.

Mystery & Thriller

You

by Austin Grossman

You is a tale of video games, obsession and the coming-of-age of five young computer nerds who started an award-winning game design company as teenagers in 1983. Austin Grossman's novel flashes back to high school, summer camp and the tentative friendships among the five while also telling the story from the perspective of Russell, the 28-year-old game designer who returns to Black Arts Games after an aborted attempt to put his nerdy youth behind him.

Simon, the genius-level programmer of the group, is dead, while Darren, the charismatic yet self-loathing leader of the company, has just left to start his own game company. Lisa, the polymath token female of the group, Don, the hanger-on middle manager, and Russell must find the truth Simon hid deep in layers of code and game mechanics before his death.

Grossman (Soon I Will Be Invincible) is a video game design consultant with a long history in the gaming industry, and he's filled You with authentic atmosphere and personality types. Alternating between third- and second-person voices, he captures the narrative choices of modern gaming as perfectly as he describes the arc of game development from beta to conference demo to ship date. His characters, leading and supporting alike, act with honest behavior and true emotional insight. These folks, even the video game characters that round out some of the dream sequences, both live and breathe. --Rob LeFebvre, freelance writer and editor

Discover: A poignantly told novel that is at once a compelling mystery, a coming-of-age story and a short history of modern video gaming.

Good People

by Ewart Hutton

Detective Glyn Capaldi, the star of Ewart Hutton's debut novel, Good People, screwed up big time and got relegated to the boonies of rural Wales. Nothing much goes on there, except for an occasional sheep farmer accidentally killing a protected species of bird--until a minibus gets hijacked and vanishes into the Welsh hills. Six local men, all "good people," and one mysterious woman vanish. The next morning, five people come back, and the local cops are willing to accept their fairly plausible story about what happened.

But Capaldi, an outsider, is unwilling to believe these "good guys" are telling the truth. He's worried about the fate of the woman, and determined to get to the bottom of what happened that night. As he starts digging, Capaldi discovers some uncomfortable secrets about sexual tensions and criminal activity simmering beneath the surface in this seemingly quiet region. It also quickly becomes clear that Capaldi is making people uncomfortable--but the question is whether or not they will manage to shut Capaldi up before he can convince his bosses that a crime really did take place.

Hutton's graphic, gritty mystery demonstrates that even the most idyllic places can harbor astonishing secrets. His small-town characters are believable, yet shocking, and Capaldi is surprisingly likable, despite his foul-mouthed, anti-authoritarian ways. Fans of gritty British crime writers like Val McDermid or contrary detectives like Ian Rankin's John Rebus will love Good People. --Jessica Howard, blogger at Quirky Bookworm

Discover: A beautiful woman goes missing in this gritty debut mystery set in rural Wales.

Pale Horses

by Jassy MacKenzie

Pale Horses, the fourth book in Jassy Mackenzie's Jade de Jong series, starts with a simple request. Victor Theron asks Jade, a South African private investigator, to look into the death of his fellow base jumper, Sonet Meintjies, after Sonet's parachute fails to open during a jump from a skyscraper. Because Victor had packed the parachute, he fears he'll be accused of killing Sonet.

When Jade investigates, she learns about a farm community that Sonet had helped to flourish--but which has since mysteriously disappeared. There's no trace of the people nor the animals; the buildings have been torn down. The story unfolds slowly at first, but once Jade discovers the farm's desolate remains and red streaks that look suspiciously like blood baked dry on the rocks, Pale Horses gains a sense of dread.

A subplot involving a woman named Ntombi, forced by an unknown employer to aid a killer, is also effective. Her desperation and terror are palpable, and a scene in which she risks her life to get a message to Jade is heart-pounding. The romantic triangle involving Jade, police superintendent David Patel and his wife, Naisha, is less absorbing. Jade's reactions make her seem petty at times, while Naisha's cold, calculating behavior is too easy a justification for Patel's adulterous affair. Thankfully, this storyline takes a backseat to the main plot, which is thought-provoking and disturbing because it seems entirely possible in a greedy, changing world. --Elyse Dinh-McCrillis, writer/editor blogging at Pop Culture Nerd.

Discover: South African PI Jade de Jong searches for the truth behind a disappeared farm community in the fourth book of a mystery series.

Biography & Memoir

The Invisible Girls

by Sarah Thebarge

At 27, breast cancer ended Sarah Thebarge's career, her studies and her romance. She fled across the country for a fresh start, where a chance meeting with Somali refugees, the "invisible girls" of this memoir's title, renewed her strength and her faith.

Growing up in a conservative Christian minister's family, Sarah exceeded her culture's expectations, earning a graduate degree from Yale, working as a physician's assistant and studying journalism at Columbia. She had a steady boyfriend and a well-planned future when she was diagnosed with aggressive breast cancer. She nearly died at several points during the brutal 18 months of surgeries and treatments. Her boyfriend abandoned her, friends broke their promises of support and, as her body struggled, her faith faltered as well.

Determined to start anew, she moved to Portland, Ore., where one day a game of public transit peek-a-boo with a Somali girl led to her visiting the girl's home, and soon she was fast friends with her impoverished young mother, who'd been abandoned by her husband soon after they immigrated, along with five daughters. Sarah provided, from groceries and coats to deciphering social services and social customs. Sarah's path of loss and survival parallels that of young Hadhi and her daughters, and they satisfied a mutual need for a sense of belonging--of becoming visible--in each other.

At this often painful memoir's end, Sarah imparts a sense of hope--her faith, health and the refugee family she loves are stable. Readers, caring about them all, will embrace her optimism. --Cheryl Krocker McKeon, bookseller, Book Passage, San Francisco

Discover: A young woman's memoir of her parallel journeys, reaching out to support a refugee family while recovering from cancer, and how hope and tenacity turned their lives around.

Lost in Suburbia: A Momoir: How I Got Pregnant, Lost Myself, and Got My Cool Back in the New Jersey Suburbs

by Tracy Beckerman

Word to the wise: Do NOT read Lost in Suburbia in public. You will guffaw so powerfully tears will stream from your eyes and you'll ask a young mom next to you if she can lend you one of the tissues she surely has stuffed up her sleeve. Or does she? That's what Tracy Beckerman's "momoir" is about: breaking out of her dried-snot covered mom persona and finding herself again.

Once a hip Manhattan TV producer who ate out so often her cupboards were bare, Beckerman now lives in New Jersey with two babies and no career. Expected to find fulfillment buying toilet paper in bulk at the local Costco, she hits rock bottom as she finds herself crashing into every tree in suburbia--New Yorkers don't drive much--then gets pulled over while wearing her bathrobe.

It's not easy to make the switch from blasé city-dweller to suburbanite mother, especially when a crazed, anti-peanut mom goes after you with a tennis racket. Still, a large number of former urban superwomen do move to the 'burbs when they have kids. The benefits of fresh air and more closet space to stow the playpen are obvious, though tempered by having to endure entire conversations about Days of Our Lives. Beckerman gets her cool back, though, while providing her readers with sidesplitting laughter. She gives other mothers hope that they, too, can escape their mom jeans. --Natalie Papailiou, author of blog MILF: Mother I'd Like to Friend

Discover: A hilarious debut memoir by a woman determined to trade in her mom jeans for skinny jeans and take back her street cred.

However Long the Night: Molly Melching's Journey to Help Millions of African Women and Girls Triumph

by Aimee Molloy

In her first full-length solo venture, Aimee Molloy (Then They Came for Me: A Family's Story of Love, Captivity, and Survival, written with Maziar Bahari) brings readers a beautifully rendered portrait of Senegal and its generous people, and of Molly Melching, the American who fell in love with both and dedicated herself to bringing them education on their own terms. Molloy's account of a modern-day heroine glows, and with precise, succinct strokes, she draws the reader into Senegalese lives.

Melching came to Africa first as a wide-eyed college exchange student from Illinois. From the moment she arrived, Senegal became her second home, and Melching eagerly embraced the culture and language, falling particularly in love with the villages outside the French-influenced city of Dakar. Instead of racing back to America and modern conveniences like electricity and air conditioning after her term ended, Melching chose to remain in Senegal. Noticing that schools were teaching in French when children spoke the local language, Wolof, at home, Melching began to question traditional European methods of bringing education to the Senegalese. In time, her respect for the people and society led Melching to develop educational programs that considered what the Senegalese themselves wished to learn and imparted information in their native tongue. These empowering strategies were radical at the time, but within a decade Melching had piloted a fast-growing program called Tostan ("breakthrough" in Wolof) that brought villagers education, encouraged development projects and enhanced rather than hindered villages' communal self-esteem.

What Melching didn't anticipate, what no one could have anticipated, was that Tostan held the key to empowering Senegal's women and ending the acceptance of a key piece of Senegalese culture: female genital cutting (FGC). When Molly Melching arrived in Senegal in 1974, women had suffered cutting for generations. Believing (incorrectly) that their Islamic faith required compliance with "the tradition," mothers subjected their daughters to the painful and sometimes life-threatening procedure not out of cruelty, but love. An uncut woman would never find acceptance within the community or make a good marriage, and no mother would set her daughter up for shunning.

Perhaps most impressive is Molloy's ability to translate the philosophy of a cultural mindset so different from our own. Rather than paint the practitioners of FGC as villains and Melching as the Great White Hope who rescues the next generation of girls, Molloy makes certain to portray her realistically, as a facilitator of education. It is the female Tostan students themselves, armed with new knowledge about their bodies, human rights, and religion, who refuse to allow their daughters to suffer as they have suffered with FGC and the fear that admission of pain or doubt will bring scorn and dishonor. At the same time, these women as a group are a force of nature with the ability to change the fate of their nation's girls or close their eyes and continue to embrace a tradition that, while dangerous, carries the sanctity of generations of routine. This is their biography as much as it is Melching's, and the efforts of the first village to stop FGC attract unlikely allies. From a woman who quit her role as a traditional cutter and became an anti-FGC advocate to a respected elderly man who walks from village to village in the scorching heat to spread information about the dangers of FGC to a host of mothers and grandmothers, the Senegalese women, and some supportive male counterparts, show a compassion and concern for each other that transforms a country into a family. Rather than diminish Melching's importance, Molloy's holistic approach to her subject matter shows Melching as the pebble that began the ripples. The women of Senegal bring about the change, but without Melching and Tostan, they would not have known change was needed. In fact, the word tostan is a metaphor for this effect. Cheikh Anta Diop, a Senegalese professor and politician, told a young Melching, "Literally, the word means the hatching of an egg.... That chick becomes a hen and lays eggs... and so there are more chicks that become hens and the process continues for generations. For me, the word signifies the idea that as people gain new knowledge in a nurturing and environment they can then reach out and share it with others, who in turn do the same."

From the spirit of one woman to the might of many, Molloy delivers an inspiring narrative that proves the world can be changed through the bravery of individuals and the love of communities. --Jaclyn Fulwood

History

The Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, 1839-42

by William Dalrymple

In White Mughals and The Last Mughal, William Dalrymple introduced readers to the complicated relationships between South Asian rulers and the British East India Company in the 18th and 19th centuries. He returns to that world in The Return of a King, once again revealing a version of "British India" that is not merely, or even primarily, British.

The story of the First Anglo-Afghan War has been told often and well, most recently in Diane Preston's The Dark Defile. But where previous writers have focused primarily on the tangle of misinformation, paranoia and bad decisions that led to the destruction of the Army of the Indus by Afghan forces, Dalrymple broadens the story. Using new sources from British participants and an array of Russian, Persian and previously unknown Afghan sources, he describes the war from both the British and Afghan perspectives. Readers already familiar with the details will be fascinated in particular by excerpts from the memoir of Shah Shuja, the deposed Afghan ruler whom the British attempted to return to the throne as a shield against Russian expansion. For the first time, the Shah appears as more than a shadow puppet.

Written in an engaging narrative style, The Return of a King is a nuanced account of what one of the expedition's survivors described as "a war begun for no wise purpose." The analogy with modern events, which Dalrymple makes at the end of the book, is inevitable but clumsy in comparison. --Pamela Toler, blogging at History in the Margins

Discover: A new perspective on Britain's 19th-century war in Afghanistan, as Dalrymple tells the Afghans' side of the story.

Essays & Criticism

Tiger Writing: Art, Culture and the Interdependent Self

by Gish Jen

Gish Jen's elegant and wide-ranging Tiger Writing--a collection of the award-winning novelist's talks in Harvard's annual Massey Lecture series--explores the differences between Eastern and Western ideas of the self in fiction and culture, and why they matter.

When he was 85, Jen's father wrote a 32-page family history that began 4,000 years in the past, reflecting an Asian sense of connection to place and history and an interdependent idea of the self. By contrast, the Western notion of an independent self focuses on individual experience as the basis for observing and narrating the world. Jen synthesizes cross-cultural and cognitive studies with analysis of Western literature and other art forms to argue that the novel, which celebrates the truth of individual experience, could develop only in the West and expresses the core American values of individualism and exceptionalism.

Jen, the child of Chinese immigrants, loved novels because they were an "Outsiders' Guide to the Universe." She read to understand her context, not to see herself reflected on the page as her young American friends did. Both cultures influence her fiction, she writes, concluding that literary fiction is important because it can express either way of understanding oneself: "The novel knows much more than the person who wrote it."

The first edition of Tiger Writing is physically beautiful--printed on ivory paper with photos throughout, intimate in the hand and a pleasure to touch and hold. It seems fitting that a book about writing, connection and culture provides such a full sensory experience. It is a perfect metaphor for its contents. --Jeanette Zwart, freelance writer and reviewer

Discover: Gish Jen (Typical American; Mona in the Promised Land) looks at the development of the novel, holding it up to contrasting ideas of the self in Eastern and Western culture.

Nature & Environment

How Animals Grieve

by Barbara J. King

Anthropologist Barbara J. King sets out to "look at animals' actions with fresh eyes" in How Animals Grieve. Building upon her experience working with baboons, King considers species from house pets to farm animals to wild creatures--combining her own fieldwork and results of other studies to explain how humans can understand animals' grief processes without anthropomorphizing them.

King approaches her subject matter with an obvious love and respect for all animals. In several cases, she points out concerns over the research approach and ethical boundaries it may be breaching. Her anecdotal examples are powerful illustrations of the capacity for bereavement, and her unanswered questions ("Do animals read bones on the ground like we read obituaries?") provide much to think about.

She also emphasizes the importance of avoiding universal definitions of grief. Just as some humans do not display signs of grief, individuals within other species may show no outward signs of grief although many other members of the species do.

How Animals Grieve is not the definitive work on animal grief, but rather a stepping-stone to further investigation, observation and understanding. King hopes others will continue to look with fresh eyes, expand our knowledge and better understand all animals.

The ultimate importance of knowing how animals grieve is to acknowledge our own species' role in that grief and change the behaviors that ultimately and negatively affect them. King offers readers a new perspective through which to view the animal world in hopes that those changes will happen. --Jen Forbus of Jen's Book Thoughts

Discover: A compassionate, cross-species examination of how animals mourn--and why it's important to humans.

Children's & Young Adult

Mary Wrightly, So Politely

by Shirin Yim Bridges, illus. by Maria Monescillo

Author Shirin Yim Bridges (Ruby's Wish) and artist Maria Monescillo (Charlotte Jane Battles Bedtime) introduce a winning heroine who's very polite--until she needs to stand up for herself and be heard.

Bridges introduces Mary Wrightly as "a good, polite little girl who spoke in a small, soft voice" and says "please" and "thank you." Mary must often repeat herself because her voice is "so small and soft." When she tells her class, "My name is Mary and I have a baby brother," Monescillo depicts the other children carrying on with their activities, unaware that she's speaking. She conveys Mary's contentment as she spends time in (what we later learn is) her brother's room. Just before her brother's first birthday, Mary asks her mother if they can go to the toy store, so she can buy him a present. The palette of Monescillo's pastel illustrations creates continuity between Mary's school and home life, as well as the toy store, and hints at Mary's sense of inner calm and confidence--despite her quiet voice. So even though she gives up her seat on the bus, apologizes when a boy steps on her foot, and acquiesces to two shoppers who take gifts Mary had picked out for her brother, youngsters suspect that underneath her polite exterior, Mary is no doormat.

Indeed, when the moment arises, Mary finds her voice and gets what she needs. This gently paced tale shows children there's room for both courtesy and confidence. --Jennifer M. Brown, children's editor, Shelf Awareness

Discover: A winning heroine who proves there's room for both courtesy and confidence.

Cartboy and the Time Capsule

by L.A. Campbell

L.A. Campbell constructs her humorous, liberally illustrated debut novel as journal entries written by 12-year-old Hal Rifkind, to be discovered in the far future as part of a time capsule.

Hal's history teacher, Mr. Tupkin, hatched the idea as a year-long project for his students. Hal divides his journal into chapters such as "Shelter," which describes his attempts to sell his house so that he'll no longer have to sleep between the cribs of his twin "teething toddler" sisters (only to discover from a house inspector that their home is in violation of a safety code). When Mr. Tupkin loads Hal down with three textbooks so he can work to bring up his grade, Hal argues that he needs a Ziptuk E300S, but his father (who fixes gadgets for a living) insists he take to school a mended cart instead--which earns Hal the titular nickname.

Hal transmits a great deal through the telling detail, such as the photo of Mr. Tupkin's bow tie ("a modern-day fashion accessory that automatically makes you look a hundred years older") and Cindy Shano's purple braces. A mystery also creeps in: Why is Hal's best friend, Arnie, constantly talking to bully Ryan Horner, who disappears as soon as Hal approaches? Campbell balances lighter moments with Hal's more serious concerns, such as his grades and the tension with Arnie, and a mix of timelines, drawings and photos keeps Hal's journal lively. --Jennifer M. Brown, children's editor, Shelf Awareness

Discover: A funny, highly illustrated journal intended for a time capsule that reveals the personal and academic struggles of a sixth-grader.

| Advertisement nuremberg--now playing in theaters |