Jacqueline Kennedy in Her Own Sharp Words

In this age of hyperbole, it's refreshing to come across a new book truly that is historic--even if it's also rather catty.

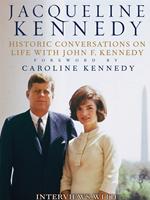

In early 1964, only months after the assassination of her husband, Jacqueline Kennedy sat down seven times with historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., as part of an oral history project on the Kennedy presidency. Their conversations, which lasted a total of six and a half hours, focused on the legacy of John F. Kennedy but also touched on her role as First Lady; the relationships between President Kennedy and his brothers; and her views on the major political figures she met. She also talked about her husband's personal opinions about figures in history, political adversaries, his reading habits and more. The interviews were recorded and then sealed at the Kennedy Library, unheard and unread by more than a handful of people. Until now. Today Hyperion is publishing Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life with John F. Kennedy, a rich multimedia title that includes 100 photographs, eight CDs of the interviews, a transcription of the interviews, an introduction and annotations by historian Michael Beschloss and a foreword by Caroline Kennedy. Excerpts quoted in yesterday's New York Times portray a First Lady who was engaged on many levels, protective of her husband and his legacy, old-fashioned about marriage and brutal in her comments on most people.

Today Hyperion is publishing Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life with John F. Kennedy, a rich multimedia title that includes 100 photographs, eight CDs of the interviews, a transcription of the interviews, an introduction and annotations by historian Michael Beschloss and a foreword by Caroline Kennedy. Excerpts quoted in yesterday's New York Times portray a First Lady who was engaged on many levels, protective of her husband and his legacy, old-fashioned about marriage and brutal in her comments on most people.

This new title fills a striking gap in the Kennedy record: the key person missing in all the millions of words written and spoken about the presidency of John F. Kennedy has always been his intensely private wife, known by the public mainly from paparazzi photographs, for her personal story, for her sense of style and, in the book world, for her work for two decades as an editor at Viking and Doubleday. "This is the first time we hear her talk in her own words about that time," said Gretchen Young, editor of the book. "It's extraordinary to hear her finally."

Caroline Kennedy is campaigning energetically for the book and will appear on a variety of shows, including tonight a special edition of ABC's Prime Time with Diane Sawyer. You'll hear a lot about this book this week and the next few months. You'll also hear an American treasure, warts and all. Happy reading--and listening! --John Mutter

Television and film actress

Television and film actress  Book you've faked reading:

Book you've faked reading:  Novelist and journalist Jonathan Raban is an Englishman in New York--and Hawaii, the Midwest and Seattle (his actual home). In Driving Home: An American Journey (Pantheon), Raban's latest work, readers learn a lot more about what things a longtime expatriate notices that natives sometimes miss, and about why Raban has chosen to call this nation his own. He looks at natural disasters, at visual artists, at family vacations and so much more in a book that combines essays with diary entries, and careful thought with on-the-spot observations.

Novelist and journalist Jonathan Raban is an Englishman in New York--and Hawaii, the Midwest and Seattle (his actual home). In Driving Home: An American Journey (Pantheon), Raban's latest work, readers learn a lot more about what things a longtime expatriate notices that natives sometimes miss, and about why Raban has chosen to call this nation his own. He looks at natural disasters, at visual artists, at family vacations and so much more in a book that combines essays with diary entries, and careful thought with on-the-spot observations. Bill Bryson's Notes from a Small Island is one man's attempt to understand Great Britain after two decades of expatriate life there, and just months before returning permanently to the U.S. Longtime Bryson fans will expect the grumpy humor and whimsical reportage here, but anyone new to this wonderful writer who doesn't find herself charmed should report to the principal's office immediately.

Bill Bryson's Notes from a Small Island is one man's attempt to understand Great Britain after two decades of expatriate life there, and just months before returning permanently to the U.S. Longtime Bryson fans will expect the grumpy humor and whimsical reportage here, but anyone new to this wonderful writer who doesn't find herself charmed should report to the principal's office immediately. The Towers of Trebizond by Rose Macaulay is not only a classic of travel writing, but also a monument to intrepid females everywhere (the intro to the latest edition is written by Jan Morris). Yes, it's a novel, but because it is so largely autobiographical, we're including it here. If you don't already know the book's famous opening line, we won't spoil it for you--but know that "Aunt Dot" is likely based on the real-life Dorothy L. Sayers.

The Towers of Trebizond by Rose Macaulay is not only a classic of travel writing, but also a monument to intrepid females everywhere (the intro to the latest edition is written by Jan Morris). Yes, it's a novel, but because it is so largely autobiographical, we're including it here. If you don't already know the book's famous opening line, we won't spoil it for you--but know that "Aunt Dot" is likely based on the real-life Dorothy L. Sayers. V.S. Naipaul is no fan of intrepid females, at least of the writing kind,

V.S. Naipaul is no fan of intrepid females, at least of the writing kind,  The top 100 titles nominated for next year's

The top 100 titles nominated for next year's  "I approached the prospect of a feature film of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy with the same misgivings that would have afflicted anyone else who had loved the television series of 32 years ago," le Carré told the Telegraph. "George Smiley was Alec Guinness, Alec was George, period. How could another actor equal let alone surpass him? My anxieties were misplaced. And if people write to me and say, 'How could you let this happen to poor old Alec Guinness?' I shall reply that, if 'poor Alec' had witnessed Oldman's performance, he would have been the first to give it a standing ovation."

"I approached the prospect of a feature film of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy with the same misgivings that would have afflicted anyone else who had loved the television series of 32 years ago," le Carré told the Telegraph. "George Smiley was Alec Guinness, Alec was George, period. How could another actor equal let alone surpass him? My anxieties were misplaced. And if people write to me and say, 'How could you let this happen to poor old Alec Guinness?' I shall reply that, if 'poor Alec' had witnessed Oldman's performance, he would have been the first to give it a standing ovation." Jay McInerney recommended his "

Jay McInerney recommended his " "

" Eric Hellman explored the concept of people who claim to love the smell of books, noting that it seems odd "until you think about the

Eric Hellman explored the concept of people who claim to love the smell of books, noting that it seems odd "until you think about the