Tuesday, April 16, 2019

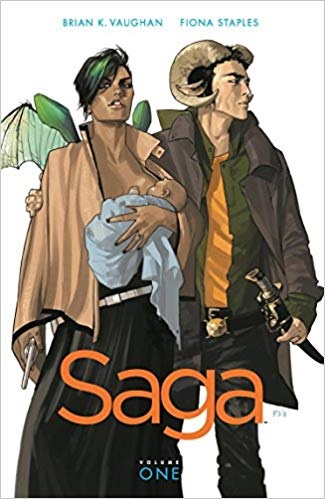

Brian K. Vaughan announced last summer that he and Saga co-creator Fiona Staples would be putting their acclaimed comic on hiatus for at least a year. That promises to be a long wait for fans of the series like me. Saga (Image Comics, $9.99) is so unusual in its fusion of genres and ideas that it's difficult to think of a substitute for the space opera love story. Instead, I have a few idiosyncratic suggestions for comics to try during the hiatus that remind me of aspects of Saga's lengthy, complex run.

Brian K. Vaughan announced last summer that he and Saga co-creator Fiona Staples would be putting their acclaimed comic on hiatus for at least a year. That promises to be a long wait for fans of the series like me. Saga (Image Comics, $9.99) is so unusual in its fusion of genres and ideas that it's difficult to think of a substitute for the space opera love story. Instead, I have a few idiosyncratic suggestions for comics to try during the hiatus that remind me of aspects of Saga's lengthy, complex run.

Saga's many characters are a flawed, charismatic, quarrelsome bunch, bringing to mind one of Marvel's most endearingly soap operatic teams, the X-Men. The super-powered mutants have decades of history behind them, but Joss Whedon's Astonishing X-Men, Vol. 1: Gifted (Marvel, $14.99) is as good a place to start as any. Whedon is excellent at keeping characters grounded and relatable under unusual circumstances, one of Vaughan's great strengths. Plus, Whedon's trademark quippy dialogue is a close cousin to Vaughan's clever lines.

Saga's many characters are a flawed, charismatic, quarrelsome bunch, bringing to mind one of Marvel's most endearingly soap operatic teams, the X-Men. The super-powered mutants have decades of history behind them, but Joss Whedon's Astonishing X-Men, Vol. 1: Gifted (Marvel, $14.99) is as good a place to start as any. Whedon is excellent at keeping characters grounded and relatable under unusual circumstances, one of Vaughan's great strengths. Plus, Whedon's trademark quippy dialogue is a close cousin to Vaughan's clever lines.

For all of its romance and humor, Saga can be a violent, disturbing comic. That and the comic's detailed worldbuilding call to mind Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda's ongoing dark fantasy epic Monstress (Image, $9.99). Liu's world has more of a baroque, horror-inflected vibe, but, like Saga, it places a heavy emphasis on the lasting trauma of war.

For all of its romance and humor, Saga can be a violent, disturbing comic. That and the comic's detailed worldbuilding call to mind Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda's ongoing dark fantasy epic Monstress (Image, $9.99). Liu's world has more of a baroque, horror-inflected vibe, but, like Saga, it places a heavy emphasis on the lasting trauma of war.

Finally, I'll recommend Tom King and Gabriel Hernandez Walta's The Vision (Marvel, $17.99). It's not necessary to know anything about Vision, a longstanding Marvel superhero, to enjoy this devastating standalone story. The Vision pairs well with Saga because of its emphasis on tragedy--despite the character's best intentions, Vision's quest to make a family is a doomed effort. During its long hiatus, Saga fans are left to wonder if Alana, Marko and Hazel will fare any better. --Hank Stephenson, bookseller, Flyleaf Books, Chapel Hill, N.C.

Finally, I'll recommend Tom King and Gabriel Hernandez Walta's The Vision (Marvel, $17.99). It's not necessary to know anything about Vision, a longstanding Marvel superhero, to enjoy this devastating standalone story. The Vision pairs well with Saga because of its emphasis on tragedy--despite the character's best intentions, Vision's quest to make a family is a doomed effort. During its long hiatus, Saga fans are left to wonder if Alana, Marko and Hazel will fare any better. --Hank Stephenson, bookseller, Flyleaf Books, Chapel Hill, N.C.

Feast Your Eyes

by Myla Goldberg

Myla Goldberg (Bee Season) goads readers at the outset of her fourth novel, "Feast your eyes, America," in the enthralling, jaded voice of Samantha Preston. Daughter of the acclaimed and controversial mid-century street photographer Lillian Preston, Samantha is the only one who can provide the necessary context for her mother's posthumous retrospective. But as the subject of Lillian's most scandalous series, she's conflicted about filling the role of curator.

Constructed as a gallery catalogue, yet notably without photos, Feast Your Eyes is a marvelous feat of the imagination. Still processing the residual trauma of her childhood notoriety, Samantha expounds on her mother's 118 photos in dialogue with Lillian's friends, lovers and diaries. "Photographs have an annoying habit of corroding whatever real memories you have of a moment until the photo is all that's left," Samantha writes about Samantha's tattoo, Brooklyn, 1959. Featuring the girl in nothing but her underpants, this picture is the first in a series deemed obscene by community guidelines.

Goldberg conjures unseen photographs with astounding skill, describing a body of work that captures Lillian's era as readily as it speaks to the author's own. Art can be a dangerous endeavor for creator and viewer alike; the greater the response, the more effective the piece. Feast Your Eyes inhabits this tension with immense grace and empathy, challenging the perennial urge to stifle what doesn't conform to a given community's standards.

The consistently ambitious Goldberg has once again delivered a remarkable piece of literature. Feast your eyes, indeed; there is much to digest. --Dave Wheeler, associate editor, Shelf Awareness

Discover: Not to be missed, Myla Goldberg's fourth novel sifts through a disruptive body of work by an innovative mid-century photographer and mother.

Mystery & Thriller

Miracle Creek

by Angie Kim

The backdraft of a boom immediately sucks readers into Angie Kim's dazzling debut, Miracle Creek. In rural Virginia, Korean immigrants Pak and Young Yoo live with their teen daughter, Mary, striving for success. Their business, Miracle Submarine, uses a hyperbaric oxygen chamber where patients undergo atmospheric pressure therapy to help with problems such as spectrum disorders, brain injuries and infertility.

Pak, a certified technician, always runs the chamber. Then one night he asks his wife to lie and leaves her alone at the controls, resulting in a compellingly layered and tragic answer to Pak's simple question "What could go wrong?" A disastrous confluence of circumstances, mistakes, emotional burdens and shame culminates in an explosion that kills two patients and injures others, including Pak and Mary.

A year later, through the murder trial of Elizabeth Ward, who stands accused of targeting her own son, who was being treated for autism, Kim masterfully unwinds the events leading up to the blast, intentionally caused by a fire. With an inordinately large pool of potential suspects in addition to Elizabeth, the various pressures that work on those associated with the Yoos and their patients paint a complicated picture that Kim mines to extraordinary effect. Protestors threaten the Miracle Submarine business, a potential insurance payout is suspicious, and marital and infertility issues raise red flags.

Kim's writing is stunning in its depth and compassion. The light she shines on the difficulties of parenting a child with special needs and the immigrant experience in the U.S. is unflinching and multi-faceted, evidence that the pressures of life can go almost unnoticed until they detonate in an instant. --Lauren O'Brien of Malcolm Avenue Review

Discover: The survivors of a medical device explosion discover the facts behind the tragedy as the trial of a patient's mother moves forward.

Biography & Memoir

Never a Lovely So Real: The Life and Work of Nelson Algren

by Colin Asher

In the postwar U.S., a Communist Party affiliation wasn't exactly a ticket to getting in the public's good graces. Even so, Nelson Algren (1909-1981) managed to make a name for himself as a socially aware writer out of Chicago, where he claimed that "every day is D-Day under the El." In the thoroughgoing Never a Lovely So Real: The Life and Work of Nelson Algren, Colin Asher sculpts the writer's checkered life story into something that would have pleased him: a ripping good tale.

Born into a working-class Jewish family, Algren graduated from the University of Illinois in 1931 with the intent of becoming a journalist. The Great Depression withered his employment prospects, so for five years Algren train-hopped and otherwise roamed in search of work and, more rewardingly, life experience, which included jail time in Texas for stealing a typewriter. Algren published a novel influenced by his travels, took odd jobs, did a stint in the army and finally had success with The Man with the Golden Arm, which, in Asher's words, "dared to assert the humanity of addicts, prisoners, prostitutes, and thieves." The book won the National Book Award for fiction in 1950.

That didn't mean Algren had it made: editors still balked when they considered his subject matter too hot, and Red Scare hysteria kept him under surveillance. Asher's grim notes on Algren's FBI file are leavened with scenes devoted to the writer's interactions (some hair-raising) with his lover Simone de Beauvoir, booster Ernest Hemingway and foe Otto Preminger. --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

Discover: This consummate biography of the writer behind The Man with the Golden Arm is something its subject would have appreciated: a great story.

History

The House of the Pain of Others: Chronicle of a Small Genocide

by Julián Herbert, transl. by Christina MacSweeney

The House of the Pain of Others: Chronicle of a Small Genocide examines a nearly forgotten tragedy: the 1911 massacre of some 300 Chinese immigrants in the city of Torreón, near the start of the Mexican Revolution. This is a work of history, but an unusual one, coming at the massacre from a multitude of angles and freely skipping through time. Writer, musician and teacher Julián Herbert (Tomb Song) frequently returns to the present day, to his reporting and reflections on what he uncovers. This gives the work a personal dimension, as does the discursive, lyrical writing. The House of the Pain of Others proves that truth does not come from a mere recitation of facts, but from the messy byways of memory and other more unexpected sources.

Despite the many tangents, Herbert's book does have a central argument, one that disagrees with the "general consensus" on the massacre at Torreón. According to the general view, the events were "an unplanned tragedy: a spontaneous reaction by the mass of common folk," which "had little or nothing to do with an act of xenophobia carried out by the people of La Laguna." Herbert argues that it had everything to do with longstanding Sinophobia fostered by the wealthy and middle class as well as the "common folk."

The House of the Pain of Others is partially about how the past haunts the present, especially if the root causes go unaddressed. Herbert claims that "this is not the story you were expecting," but in many ways it is achingly familiar. --Hank Stephenson, bookseller, Flyleaf Books, Chapel Hill, N.C.

Discover: Julián Herbert deftly combines history, journalism and essay to investigate the massacre of 300 Chinese immigrants during the Mexican Revolution.

Philosophy

Tragedy, the Greeks and Us

by Simon Critchley

Life is often violent, unjust and uncertain. In order to cope, "we need to go back to the theater... we need to see tragedy itself as a... mode of experience that can teach us," Simon Critchley (Stay Illusion!) argues in Tragedy, the Greeks and Us. The author supports his contention in this thought-provoking and formidably erudite work first by rehabilitating sophistry and using tragedy to counterpoint philosophy, which he finds insufficient in the face of reality.

Sophistry--essentially learning to argue any position irrespective of truth--was scorned almost from its inception, starting with Socrates (circa 450 BCE) and his adherents. Critchley considers sophistry as a prototypical form of modern subjectivity, which is more nuanced and subtle than the truth-seeking of philosophy and better reflects the messiness of existence.

Tragedy shares much with sophistry, avoiding certitude, considering first one position and then the opposite. Therefore, tragedy has explanatory power as "human beings' relation to the world is a marriage of convenience or adaptation made neither in heaven nor in nature, but on the slaughter bench of history," and "our lack of vocabulary when it comes to the phenomenon of death speaks volumes about who we are and what is so impoverished about us." Tragedy teaches us an essential vocabulary to cope with the human condition.

Passing familiarity with the 31 surviving Greek tragedies and the ideas of Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Spinoza, Hegel, Heidegger, Nietzsche, among others, is sufficient to make this work rewarding and provoking. When necessary, Critchley does the heavy lifting. --Evan M. Anderson, collection development librarian, Kirkendall Public Library, Ankeny, Iowa

Discover: Tragedy, the Greeks and Us is a revitalizing and intelligent exploration of an ancient form.

Psychology & Self-Help

Mind Fixers: Psychiatry's Troubled Search for the Biology of Mental Illness

by Anne Harrington

In Mind Fixers: Psychiatry's Troubled Search for the Biology of Mental Illness, historian of science Anne Harrington illuminates a complicated history that has had profound, if not entirely recognized, effects on American culture.

Mind Fixers is organized into three parts. The first is a comprehensive history of the profession of psychiatry from the 1870s to the 1970s, with its incredible breakthroughs, professional rivalries and dubious practices. Harrington deepens the nonlinear nature of this history in the second part of the book by focusing on psychiatry's attempts to understand and treat three different illnesses--schizophrenia, depression and bipolar disorder--in biomedical terms.

In part three, Harrington shows that the 1980s marked a turning point, as the discipline's "biological revolutionaries" shook off the grip of lingering Freudian ideologies and took the discipline firmly in the direction of neuroscience, biochemistry and--of course--drugs. But, Harrington argues, this "optimistic biological psychiatry" unraveled in the 1990s and 2000s, in part because the profession's relationship with the pharmaceutical industry became increasingly problematic and, even more importantly, consistent biological bases for mental illness have remained elusive.

Deeply researched and thoughtfully organized, Mind Fixers is far from a myopic, academic slog. Instead, Harrington--with the rigor of a scholar, the drive of a reformer and the benefit of an outsider's perspective--cracks the insular discipline of psychiatry open, confronts its sometimes dark history and connects its professional identity issues to policies and campaigns that have played major roles in the lives of Americans since the 19th century. --Hannah Calkins, writer and editor

Discover: Mind Fixers will captivate those interested in mental illness, the history of medicine and the scientific, cultural and political ramifications of psychiatry's shifting professional identity.

Nature & Environment

Down from the Mountain: The Life and Death of a Grizzly Bear

by Bryce Andrews

Humans have long feared bears. But in Down from the Mountain: The Life and Death of a Grizzly Bear, former rancher Bryce Andrews (Badluck Way) explains why bears should be afraid of us. This beautifully written story begins with a look at Andrews's ranching days near the mountains in Montana. Raising cattle in bear country, he'd seen his fair share of grizzlies. "Such encounters were commonplace," he writes. "Bears left tracks in mud and snow, and I learned to be cautious."

His love for all animals, wild and domesticated, set him on a new career path, and today he works with the conservation group People and Carnivores. It was as a rep for that group that Andrews decided to ask farmer Greg Schock if he could try building an electric fence around his corn field to keep out bears. More than a dozen grizzlies were getting into that corn in late summer, destroying a good part of the crop--a scenario that put both the farm workers and the bears at risk of hurting each other.

As the book unfolds, it becomes much more than a tale about an ex-rancher building a fence. It's a meditation on the meaning of wildlife, the threat of human development, and the transformation of the American West. Intertwined is a story about Millie, a grizzly mother with two cubs who has a fatal run-in with a human. Well observed and deeply moving, Down from the Mountain is one of the finest works of nature writing in recent memory. --Amy Brady, freelance writer and editor

Discover: This affecting and lyrical book explores how bears and humans are learning to live together in the quickly developing American West.

Eating the Sun: Small Musings on a Vast Universe

by Ella Frances Sanders

From the author of Lost in Translation, a captivating compendium of words untranslatable into English, comes another wondrous read: Eating the Sun: Small Musings on a Vast Universe. This slim but remarkable volume by Ella Frances Sanders explores the marvels of the universe, from the very tiny (atoms and cells) to the very large (supercluster galaxies).

Comprised of short chapters no more than a couple pages each, the book eschews hard science for more elementary facts that read like poetry. "You are made from the remnants of stars," Sanders writes. "Strung up like fairy lights... the stars are to thank for your singular fragile body." She goes on to explain in equally lyrical prose how every living thing on Earth contains carbon from the cosmos. In the standout chapter "I'll be Where the Blue Is," Sanders explains that "blue as a color in nature is actually incredibly elusive," because it's produced by a trick of light. The natural magic trick is responsible for the color of the North American blue jay as well as the sky on a summer day.

Like its predecessor, Eating the Sun is full of word appreciation. In Sanders's chapter about the orbits of planets, she writes that "we should be glad that orbits are not perfectly circular" because it allows us to describe the phenomenon as "perihelion," a word that's "enough to make a person weak at the knees." Between the chapters are colorful drawings that, like her writing, encourage a childlike awe. --Amy Brady, freelance writer and editor

Discover: This slim but lyrical exploration of the universe elicits poetry and awe out of science.

Performing Arts

Best. Movie. Year. Ever.: How 1999 Blew Up the Big Screen

by Brian Raftery

The sheer amount of cinema classics released in 1999 is mind-boggling: films such as The Sixth Sense, The Blair Witch Project and The Iron Giant have endured in modern pop culture as truly great movies. (Others, like Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace--not so much.) In the thoughtful and entertaining Best. Movie. Year. Ever., film critic Brian Raftery recounts the production and aftermath of seminal 1999 movies. He interviews dozens of directors, actors and writers involved in each film, gathering stories and anecdotes demonstrating why these movies still matter, sometimes in discomfiting ways. Raftery argues persuasively that American Beauty is more relevant to 2019 audiences than ever before, for example.

He makes the case for 1999 as a pivotal moment in pop culture, a time when low- or mid-budget films could be funded by major studios, and television didn't dominate mainstream storytelling. The Matrix and Fight Club even predicted the sea change in how Americans would interact with each other, forming relationships and political movements all via the Internet. If there's a mournful quality to the epilogue on how much things have changed--such as Kirsten Dunst lamenting the decline in quality of modern movies--there's excitement, too: a film year like 1999 could happen again just as people have given up hope. Ultimately Best. Movie. Year. Ever. is an engaging and brilliantly researched book on, as Raftery calls it, "the most unruly, influential, and unrepentantly pleasurable film year of all time." --C.M. Crockford, freelance reviewer

Discover: A film critic offers a deeply satisfying and joyful look into the amazing film year of 1999.

Poetry

The Tiny Journalist

by Naomi Shihab Nye

In 2013, Janna Jihad--then just seven years old--began filming and posting videos that captured snippets of her daily life as a Palestinian living under Israeli occupation. Her videos caught the attention of thousands around the world, including Palestinian American poet Naomi Shihab Nye (19 Varieties of Gazelle; Voices in the Air). Her collection The Tiny Journalist takes its title from Janna, and its poems--some of which are written to the girl--address the maltreatment of Palestinians by Israel and its allies, including the United States.

"How lonely the word PEACE is becoming./ Missing her small house under the olive trees," Shihab Nye writes in "For Palestine." A sense of weariness pervades some of the collection: fittingly, there is a poem called "How Long?" and one called "Patience Conversations." Even the poems that are ostensibly about daily life are tied to the conflict: "Studying English" begins with a musing on how the word courage "has age/ in it/ but I say/ age is not required." "Mediterranean Blue" jumps straight from the sea's color to a meditation on refugees, and ends with a pointed statement: "And if we can reach out a hand, we better."

On every page, Shihab Nye's insistent call is the same: people, all people, deserve to live safe and healthy lives, free from fear and violence. Her poems are a clarion call to readers to see the violence in Palestine and elsewhere, and to do what they can to work for peace. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams

Discover: Naomi Shihab Nye's latest poetry collection addresses the ongoing violence in Palestine and makes a powerful call for peace.

Children's & Young Adult

Riverland

by Fran Wilde

"Someday... our real parents will come for us." This is what Eleanor and little sister Mike tell themselves when the fighting between Poppa and Momma gets too loud. "Some days" the sisters can "sense trouble coming. Other days, like the weather," it catches them "by surprise." But, as long as they follow the rules, "house magic" will protect them and make everything perfect again, erasing all signs of trouble. Unfortunately, although Eleanor always works to do the right thing, nothing ever happens as she plans. "Adults [are] unpredictable. And there [is] no right answer. Only something in between right and wrong."

When a magical river appears under Eleanor's bed, the sisters fall into the land where dreams and nightmares are born. The river is leaking into the real world, and if left untended, nightmares will break through the cracks. Eleanor and Mike discover that there is a generations-old family agreement to act as guardians of the boundary--it's now their turn to fix the leaks and keep the nightmares at bay. But, as Eleanor asks herself, "How do you patch holes in dreams? In families?"

With her middle-grade debut, award-winning author Fran Wilde (the Bone Universe trilogy) depicts two girls attempting to make sense of the emotional and physical abuse they suffer from and witness every day. Wilde approaches the difficult subjects of domestic violence and emotional abuse with the care and respectful treatment that they deserve, using the fantastic to symbolize and illuminate the complex emotions her characters experience. About courage and truth overcoming denial and fear, Riverland is an important book. --Jennifer Oleinik, freelance writer and editor

Discover: In Fran Wilde's middle-grade debut, Riverland, when the magical realm of dreams and nightmares starts leaking into the real world, abused sisters Eleanor and Mike work to seal the breach.

Her Fearless Run: Kathrine Switzer's Historic Boston Marathon

by Kim Chaffee, illus. by Ellen Rooney

Young Kathrine loves to run. She sprints around her backyard while passersby look on quizzically: in 1959, "girls weren't supposed to sweat. Girls weren't supposed to compete. They were too weak, too fragile, for sports."

Later, attending Syracuse University, Kathrine finds that there's no women's running team. She's permitted to practice with the men; the team's manager, who has run the Boston Marathon 15 times, identifies and nurtures Kathrine's gift. On the day she runs 31 miles, they both know that she's ready for Boston.

Unfortunately, in 1967, Boston isn't ready for her, or for any woman who wants to run the 26-mile marathon: in its 70-year history, only men have been granted race numbers. However, when Kathrine checks the marathon's rule book and entry form, she sees nothing about "only for men." She registers as "K.V. Switzer," and the rest, as they say, is history. (Not that Kathrine's run was without obstacles: two race officials who believed that women didn't belong in the contest tried physically to derail her mid-stride.) At the finish line, she's plainspoken with reporters who ask why she competed: "I like to run. Women deserve to run too."

Her Fearless Run: Kathrine Switzer's Historic Boston Marathon finishes ahead of the typical picture book biography. Bolstered by sources including Switzer's 2007 memoir, the book is distinguished by Kim Chaffee's obvious enthusiasm for her subject and by Ellen Rooney's multifaceted mixed-media collage art, which offers a steady supply of interesting backdrops, both realistic and abstract, past which Kathrine flies. --Nell Beram, freelance writer and YA author

Discover: The first woman officially to run in the Boston Marathon gets her due in this ebullient picture book biography.