| Publisher: | Little, Brown | |

| Genre: | Multiple Timelines, World Literature, England - 21st Century, City Life, Literary, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9780316552851 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $29 |

| Starred | Fiction |

by Tom Rachman

In Tom Rachman's cunning The Imposters, his fifth book, an aging novelist reevaluates her mediocre career, and ponders those who have played roles in her personal or professional life. As she composes her final work, the intriguing question is whether life follows art--or vice versa. Rachman (The Italian Teacher) returns to the linked short story format of his debut, The Imperfectionists. The novel opens and closes with "The novelist," Dutch 70-something Dora Frenhofer, who now lives in London. In between, seven chapters depict people whose lives intersected with hers. There's her missing brother, Theo, who traveled in India in the 1970s; her estranged daughter, Beck, a comedy writer in California; her last remaining friend, Morgan, whose two children were murdered; and a former lover. But there are also characters who crossed paths with her only briefly, such as a fellow writer at a literary festival and a deliveryman.

The close third-person segments are rich in detail and characterization. Passages from Dora's diary, ranging from December 2019 to September 2021, reflect on these personal connections--and reveal her incipient dementia. The last line of each entry is then repeated as the first line of the next story; what with that and the final chapter's revelations, readers are invited to consider whether Dora is documenting what actually happened or masterminding it for a fictional plot--with an ending of her choice. In this wry, incisive novel, Rachman revisits his trademark themes of creativity, loss, and failure, and comments on pandemic-era existence. --Rebecca Foster, freelance reviewer, proofreader and blogger at Bookish Beck

| Publisher: | Berkley | |

| Genre: | Women, General, Biographical, African American & Black, Fiction, Historical | |

| ISBN: | 9780593440285 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $28 |

| Starred | Fiction |

by Marie Benedict, Victoria Christopher Murray

Two powerful American women form a friendship that enriches their lives and changes the course of history in The First Ladies, the second mesmerizing and revealing historical novel by Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray (The Personal Librarian). Eleanor Roosevelt and Mary McLeod Bethune meet at a Manhattan ladies' luncheon in 1927; Eleanor is the daughter-in-law of the hostess, society matron Sara Delano Roosevelt, and Mary is president of both the National Association of Colored Women Clubs and Bethune-Cookman College. The other guests do not conceal their racist shock. The 18-year arc of the novel ends in 1945, the fast friends clasping hands at the vote for the Charter of the United Nations, which addressed global equal rights.

Narrated in alternating chapters, Eleanor and Mary often provide two perspectives on the same scene, revealing the respect between the First Lady and "the First Lady of the Struggle." The tenacious women, often criticized, are committed to civil rights, including controversial anti-lynching legislation, as the United States edges toward World War II. They also focus on equality for Negroes in the military, relying on Eleanor's access to the president. A heartening story of friendship, The First Ladies also presents distinct perspectives on American history, including social and political roadblocks to racial equality and the behind-the-scenes support and loyalty between Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt. "We're missionaries in our own land, normalizing the integration of the races," Mary observes of the inspiring, iconic team. --Cheryl McKeon, Book House of Stuyvesant Plaza, Albany, N.Y.

| Publisher: | Simon & Schuster | |

| Genre: | Women, Family Life, Humorous, General, Marriage & Divorce, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781982158798 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $27.99 |

| Starred | Fiction |

by Carolyn Mackler

Carolyn Mackler's razor-sharp adult fiction debut imagines one answer to a persistent question: What if women got paid for all the "mental load" tasks that wives usually do for free?

After she finds out her husband is cheating (again), Manhattan tech product manager (and mom of twins) Lauren Zuckerman files for divorce. While toasting her new life, she and her two best friends, Madeline and Sophie, hit on an idea: a "wife app" that would pay women to wrangle the minutiae of other people's lives. Though the other two initially see it as a joke, Lauren takes the idea and runs with it, resulting in a wild ride that will reshape how they all think about work and relationships.

Mackler (The Universe Is Expanding and So Am I) shifts among her three protagonists' voices, chronicling their struggles with career and parenting, as well as their larger existential (and romantic) worries. As the women work out the kinks of the app--accepting assignments, establishing firm boundaries with clients, hiring other "wives" and juggling their new workloads--Mackler examines the cultural norm of women shouldering the mental (and logistical, and often emotional) burdens for their families. Her characters grapple (sometimes hilariously) with the growing pains of a start-up and its sudden success, but still have to manage their own mental loads. Throughout the book, their friendship--not perfect, but honest and warm--helps ground all three women.

Smart, wincingly funny, and occasionally sexy, Mackler's novel is a 21st-century ode to female empowerment and women pursuing what they really want--while still juggling childcare, camp forms, and relationships like the pros they are. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams

| Publisher: | Europa Editions | |

| Genre: | LGBTQ+ - Lesbian, Romance, Literary, Lesbian, Erotica, Fiction, LGBTQ+ | |

| ISBN: | 9781609458409 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $18 |

| Starred | Fiction |

by K Patrick

K Patrick's mesmerizing debut, Mrs. S, is atmospheric and disorienting in the most effective way. The unnamed narrator, the Matron at a girls' boarding school in the English countryside, calls her charges "The Girls," also unnamed throughout. The details readers learn of her surface through others' observations or direct questions: a bookstore clerk apes her Australian accent; a bartender questions her age ("You work at the school?... Not a student?"). Dialogue runs together with no quotation marks and no sign of who is speaking. But Patrick shows readers how to detect the nuances of observation and conversation, and they view events as the narrator does, burrowing ever deeper into the world of Mrs. S.

The title character appears on the first page: "Her energy is concentrated and precise, light through a magnifying glass." The narrator's obsession with Mrs. S grows from there. Theirs is a forbidden tryst; Mrs. S is the headmaster's wife. They steal a moment for a smoke in an abandoned van behind a gas station after church, an embrace in the kitchen as Mrs. S prepares dinner--all building up to their lovemaking in the vestry of the church. The claustrophobia of the school and its web of rumors makes the clandestine relationship all the more miraculous, and Patrick's sharp, pithy sentences underscore its suffocating environment ("The school pretends to be a town"). The scenes between the Matron and Mrs. S stop time, open borders, emancipate them. Yet it is an impossible connection. How can it end? Patrick will keep readers turning the pages to find out. This is a writer to watch. --Jennifer M. Brown, senior editor, Shelf Awareness

| Publisher: | Anchor | |

| Genre: | Women, Family Life, Humorous, General, Marriage & Divorce, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9780593469170 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $26 |

| Fiction |

by Elizabeth Castellano

"I'm that kind of person. The worst kind of person. I'm a beach person," claims the narrator near the outset of the hilarious Save What's Left, Elizabeth Castellano's fictional tell-all about Kathleen Deane's descent into beach-town mayhem. The 50-something recent divorcee sells her Kansas home and purchases, sight unseen, a fixer-upper beach house on Long Island. The problem, of course, is that Kathleen is not the kind of beach person she imagined she'd become--strolling sandy shores and soaking in the sun--with the purchase of this new home following her husband's unexpected departure. Instead, she bemoans, "I'm now the kind of horrible person who genuinely cares about what so-and-so had to say about the traffic from the chowder festival," and has a box full of paper complaints that "began as minor grievances but are now exhibits in a money-laundering scheme."

It's easy to romanticize small-town, beachside life; who hasn't dreamt of giving it all up in favor of a simpler way of living? But in her debut novel, Castellano reveals something like a hidden underbelly in this too-common dream: bickering neighbors, ugly construction, never-ending parking nightmares. As the capers of Kathleen's neighbors, though, become more and more over-the-top, Save What's Left becomes something of a parody of beach-town living, packed with laugh-out-loud moments of absurdity, and touching moments of community and camaraderie found in unexpected corners. An easy, breezy delight from start to finish, Save What's Left is a charming, comedic tale of one woman's quest to reinvent herself--and perhaps reinvent her new town in the process. --Kerry McHugh, freelance writer

| Publisher: | Kensington | |

| Genre: | Psychological, Romance, Time Travel, Gothic, Thrillers, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781496742629 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $16.95 |

| Fiction |

by Marielle Thompson

Lush descriptions and strong emotions fill Where Ivy Dares to Grow, a debut gothic fantasy by Marielle Thompson about the imperative of self-love. Saoirse Read is engaged to wealthy British aristocrat Jack Page--not that she cares about his money or status. She only cares that Jack shows her the attention and love she never got from her own family back in the United States. Jack's parents, on the other hand, never approved of Saoirse. When she falls victim to a disorder that plays tricks on her mind, her relationship with Jack starts disintegrating as he deals with her illness by trying to mold her into the wife his parents want her to be.

With Jack's mother on her deathbed, the couple heads to Langdon, the Page estate in the English countryside. There, Saoirse struggles to find her place in the estate, in her life, and in her own body and mind. When Langdon mysteriously sends her from 1994 to 1818 and she meets Jack's ancestor, Theodore Page, who sees her and loves her for who she is without trying to change her, Saoirse begins to see the world--and herself--in color again.

Thompson's writing style echoes a mind in the thrall of mental illness and allows readers to see events from Saoirse's perspective. Though Langdon's time-slips are the catalyst for Saoirse beginning to believe that she deserves unconditional love and isn't hopelessly flawed, Saoirse rescues herself from the doomed relationship she has found herself in. Where Ivy Dares to Grow, an immersive debut, does a great deal to counter the stigma of mental illness. --Dainy Bernstein, literature professor, University of Illinois

| Publisher: | Berkley | |

| Genre: | Women, Romantic Comedy, Romance, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9780593336502 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $17 |

| Romance |

by Ashley Poston

Ashley Poston (The Dead Romantics) presents another irresistible romance with paranormal elements in The Seven Year Slip, the perfect summer escape for romance readers and time-travel aficionados alike. Clementine, a publicist for a New York City publisher, struggles with the recent loss of her beloved Aunt Analea; she's simply going through the motions with her co-workers and friends. Analea left Clementine her apartment, which she always described as magical, but Clementine doesn't believe it... until the day the apartment introduces her to Iwan. Terrified by the intrusion of a stranger, even a handsome stranger with a Southern drawl, Clementine is even more surprised to discover he is subletting the apartment from Analea--seven summers ago. To Clementine's disbelief, outside the apartment her life and work continue as normal. But occasionally she goes through the door, and she's seven years in the past. Iwan's gregarious charm helps soothe Clementine, and their delightfully romantic bubble makes her incredibly happy--until the day she meets seven-years-older Iwan outside and finds him completely changed.

This nuanced, introspective novel is both humorous and a little sad, but it is mostly a testament to the abilities of humans to change. Poston ably portrays grief and love (plus a pair of violent pigeons) with quirky charm. The tiny bit of time travel makes the story perfectly magical, and fans of Beth O'Leary or Carley Fortune are sure to enjoy Clementine and Iwan's burgeoning relationship. --Jessica Howard, freelance book reviewer

| Publisher: | Knopf | |

| Genre: | Cooking, Middle Eastern, Regional & Ethnic, Specific Ingredients, Asian, Natural Foods | |

| ISBN: | 9780593320747 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $40 |

| Food & Wine |

by Nasim Alikhani, Theresa Gambacorta

Sofreh: A Contemporary Approach to Classic Persian Cuisine by Nasim Alikhani, with Theresa Gambacorta, is a heartfelt, warm embrace of a book, filled with stories of home, the pleasure of feeding others, and the saffron-studded sensuality of delicious Iranian home cooking. Alikhani launched into the New York culinary scene in 2018, on the cusp of her 60th birthday. Since then, her career has soared, including her recent stint at the White House preparing dishes for a special Iranian new year celebration. In her debut cookbook, named after her Brooklyn restaurant, she uses the words "Persian cuisine" and "Iranian food" interchangeably, with geographical and historical explanations for how those terms overlap.

Sofreh introduces food categories in order of their importance at the family table. Bread is the "primary pillar," followed by dairy and rice. Alikhani notes that herbs are used in Iranian cooking more than in any other cuisine; a platter of fresh herbs is typically served at the start of every meal. Though recipes for meat, poultry, and seafood dishes abound, followed by pickles and a splendid chapter on sweets, vegetarians and vegans will find plenty of recipe options to explore. Alikhani also devotes a chapter to "a'ash," a stew made from beans and other legumes, cracked wheat, and freshly chopped herbs. Garnished with mint oil and crispy onions, it is the ultimate vegan comfort food.

Readers will want to linger over Quentin Bacon's many gorgeous photos, including one for a colorful "jeweled rice." With quotes from Alikhani's mother sprinkled throughout, Sofreh is a deeply personal and passionate homage to Persian hospitality. --Shahina Piyarali, reviewer

| Publisher: | Doubleday | |

| Genre: | True Crime, Europe, Ireland, General, Murder, History, Historical | |

| ISBN: | 9780385547628 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $29 |

| Starred | Social Science |

by Mark O'Connell

Irish journalist Mark O'Connell's A Thread of Violence is an engrossing and intimate glimpse into the psyche of an actual yet improbable murderer.

Over the course of a few weeks in the summer of 1982, 37-year-old Malcolm Macarthur, debonair heir to a large country estate in County Meath, savagely bludgeoned to death Dublin nurse Bridie Gargan, in the act of stealing her car; killed Donal Dunne with a shotgun he ostensibly intended to purchase from the young farmer; and botched an armed robbery from a onetime acquaintance. Macarthur's one-man crime wave was part of his desperate plan to right his sinking financial ship, after he had squandered his share of the proceeds from the sale of his family's rural homestead.

O'Connell (Notes from an Apocalypse) had been fascinated with Macarthur's bizarre story ever since he learned, as a child, that the killer had been apprehended in an apartment in the same suburban Dublin complex where his grandparents lived. After a handful of chance encounters on the streets of Dublin--where Macarthur lived openly, following his release from prison in 2012--O'Connell decided he wanted to write about a man he admits "compelled me like a haunting." For roughly a year, he engaged someone he came to think of as a "character from a novel manifested in the physical world" in wide-ranging conversations.

O'Connell is a patient, thorough interlocutor, especially in conversations where his predominant feeling was frustration with Macarthur's rationalizations and evasions. The insights O'Connell offers into his own emotions are also revealing, producing a case study about the chilling ease with which one man can be driven to murder. --Harvey Freedenberg, freelance reviewer

| Publisher: | Thames & Hudson | |

| Genre: | Architecture, Buildings, Monographs, General, Individual Architects & Firms | |

| ISBN: | 9780500025406 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $75 |

| House & Home |

by Skylab, Jeff Kovel

Skylab: The Nature of Buildings is the first architectural monograph from Portland, Ore., design firm Skylab. This cleverly conceived book highlights some of the most impressive work out of the Skylab studio since its founding by Jeff Kovel in 1999. Visually, it presents as a double album, with its distinct square shape and circular cutout in "sides" (A, B, C, D) and "tracks" and, like any greatest-hits compilation, it focuses on the creative philosophy of the firm, and its evolution over time.

In her introduction, architecture and design critic Mimi Zeiger lauds the innovation and experimentation of the studio principals: "Skylab is just as much an object lesson in how success depends on possible failure. Ambition necessitates risk." That risk-taking is evident in this volume, and readers will appreciate the creativity and intentional design throughout. As in any speculative endeavor, not every choice will be equally loved, but from the lime-green font to the foldout posters, this book does not shy from bold decisions. Its creators know what the volume is and lean heavily on its strengths. Fans of architecture and design will revel in the images (more than 400 full-color, large-format photos), and the multiple interviews and descriptions behind such projects as the Serena Williams Building on Nike's campus or the Columbia Building in Portland. Hefty and full of quirk, Skylab: The Nature of Buildings would make a great gift for any creative, perfect for coffee-table perusal or the kind of deep dive into the liner notes familiar to the superfan. --Sara Beth West, freelance reviewer and librarian

| Publisher: | Scribner | |

| Genre: | Family Life, Humorous, General, Literary, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781501144073 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $17 |

| Now in Paperback |

by Tom Perrotta

Tracy Flick, the ambitious but unlucky protagonist of Tom Perrotta's 1998 novel Election, is back and still striving in the standalone Tracy Flick Can't Win. Perrotta (The Leftovers; Little Children) serves up his signature black comedy and shrewd wit in an expertly paced novel. Tracy, now 40-ish, works as assistant principal at Green Meadow High School in a New Jersey suburb, whose football team disappoints everyone in town. Life hasn't turned out as Tracy had hoped. She left law school to care for her mother, whose death 10 years ago still leaves a gaping hole. Instead of being a high-powered attorney, Tracy serves as the hardworking second-in-command at a public high school. When Principal Jack Weede announces his retirement, it might finally be Tracy's time to shine.

Kyle Dorfman, one of Green Meadow's most successful alumni, has the idea of putting together a Hall of Fame. (He's also the new school board president.) The first meeting of the selection committee immediately turns sour: the obvious candidate is a former star quarterback, and Tracy's seen this routine before. Chapters shift in perspective, mainly between Tracy Flick, Jack Weede and Kyle Dorfman, whose first-person voices are joined by those of the two students who serve on the selection committee. These points of view paint Green Meadow--and Tracy--in different lights, and allow Perrotta's comedic zings to shine.

Tracy sees the world changing around her but hasn't entirely figured out her own version of it yet. She's still ambitious but worried it may be too late for her. By the end, Tracy is headed either for the triumph she's been seeking since high school, or a meltdown the likes of which Green Meadow has never seen--or maybe both. --Julia Kastner, librarian and blogger at pagesofjulia

| Publisher: | Riverhead | |

| Genre: | Dystopian, Political, Fiction, Alternative History | |

| ISBN: | 9780525534914 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $17 |

| Now in Paperback |

by Lidia Yuknavitch

Lidia Yuknavitch's Thrust is a complex novel of great imagination. At its center is Laisvė, also known as the Water Girl. In the late 21st century, she and her father hide away from what is left of society in a submerged New York City where only the tip of Lady Liberty's torch is visible at low tide. Laisvė has a fascination with curious objects and an unusual set of skills. "She knew not to be afraid to go to water, because time slips and moves forward and backward, just as objects and stories do." Laisvė is a carrier, who can move not only objects but people through time as well as space. In Yuknavitch's lovely, weird prose, Laisvė will eventually connect Frédéric, the French sculptor of the Statue of Liberty, and his captivating, beloved cousin Aurora; a violent, abused boy and the social worker--the daughter of a war criminal--who hopes to save him; and a tight-knit crew of three men and one woman who help build the Statue, and who represent "an ocean of laborers."

Yuknavitch (The Misfit's Manifesto; Verge; Dora: A Headcase) moves between worlds as her chapters follow different characters in turn. Thrust is many things: a speculative history of the United States, a recognition of forgotten classes, a fluid song about the power of love, a celebration of the power of language and storytelling. It is an intricate novel in its interconnections, plotlines twisting away and back together again, but readers' attention will be well rewarded by profound, thought-provoking and deeply beautiful observations about humanity in an ever-changing world. --Julia Kastner, librarian and blogger at pagesofjulia

| Publisher: | Hogarth | |

| Genre: | Sagas, General, Literary, Fiction, Historical | |

| ISBN: | 9780451495211 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $18 |

| Now in Paperback |

by Anthony Marra

Mercury Pictures Presents is the outstanding third work of fiction from Anthony Marra (A Constellation of Vital Phenomena; The Tsar of Love & Techno). Although Marra may have panned away from the distressed Chechen settings of his first two books, instead choosing to focus on grandiose Hollywood backdrops for this novel, the treacheries of war and propaganda continue to emerge as a profound theme in his work.

Maria Lagana is an Italian émigré who works for Mercury Pictures, a B-grade studio owned and operated by the unscrupulous Feldman brothers, Artie and Ned. Her job is to slip illicit content past the stringent Production Code censors of 1941. One such film illustrates the power of propaganda and happens to explode into the mainstream at a crucial moment in history. Soon after, the U.S. War Department taps Mercury to make pictures that promise to drum up support for American involvement in World War II.

Marra quickly and nimbly expands this premise into CinemaScope, establishing depth and nuance for even his most marginal characters. Throughout the novel, foreign nationals who had narrowly escaped the rise of fascism in Europe awaken to an adoptive country spiraling into its own forms of jingoistic paranoia. Yet Marra's belief that hope and the human spirit can triumph over hatred and cynicism never falters. He has crafted a dazzling historical novel that sparkles with buoyant humor and resilient characters, in spite of the atrocities that entangle them. Mercury Pictures Presents is a marvelously smart and delightfully absorbing novel from a writer who continues to one-up himself, and appears to take great joy in doing so. --Dave Wheeler, associate editor, Shelf Awareness

| Publisher: | Back Bay Books | |

| Genre: | Humorous, General, Literary, Fiction, Gay, LGBTQ+ | |

| ISBN: | 9780316498913 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $17.99 |

| Now in Paperback |

by Andrew Sean Greer

In Less Is Lost--the follow-up to the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Less by Andrew Sean Greer (The Impossible Lives of Greta Wells)--Arthur Less is on the road again. This time he travels the U.S. instead of overseas. Narrator Freddy Pelu, Less's lover, returns, too. Freddy, who is approaching 40, lives with 50ish "Minor American Novelist" Less in a San Francisco bungalow they call the Shack, previously owned by Less's former lover, poet Robert Brownburn. After Robert dies, Less learns he owes a decade's back rent to the estate. While Freddy narrates from his sabbatical in Maine, the novel follows Less on his money-making travels through the South, Southwest and Mid-Atlantic as he drives a famous science fiction writer and his pug to Santa Fe in an RV that "vibrates dramatically"; accompanies a theater troupe on performances of one of his stories; and fails to do his part while serving on a committee for a literary award.

Some readers might feel this novel is merely part two of Less, but a much more apt comparison is to Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita in that both are portraits of America from characters who consider themselves outsiders. The novel has one exquisite line after another; for example, Freddy describes himself as a man whose "curls have patinaed like scallops on old silver."

"America, how's your marriage?" Freddy asks at one point. Less Is Lost is more than just a gorgeously written sequel. It's also a perceptive observer's entertaining assessment of whether a breakup of the American nuptials is imminent. --Michael Magras, freelance book reviewer

| Publisher: | Holt McDougal | |

| Genre: | Hispanic & Latino, Cultural Heritage, Literary, Southern, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781250871527 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $16.99 |

| Now in Paperback |

by Kimberly Garza

In her stunning debut novel, The Last Karankawas, Kimberly Garza takes readers into the intertwined lives of Filipino and Mexican American residents of Galveston, Tex., and surrounding communities. At the center of her narrative are Carly Castillo, who is torn between her love for her home and her secret desire to go somewhere new, and Carly's grandmother, Magdalena, who insists that their family is descended from the Karankawas, a "vanished" Indigenous tribe. Carly's Filipina mother, Maharlika, is mostly conspicuous by her absence: she left when Carly was six years old and they haven't seen her since. As Carly grows, she and Magdalena learn to navigate new layers to their relationship, especially as Magdalena's memory begins to fail.

Garza introduces her characters through a series of linked stories, each focusing on a different character: Carly's boyfriend, Jess, a star shortstop who falls in love with fishing; Jess's undocumented cousin, Mercedes; Magdalena's day nurse, Kristin; Kristin's brother, Pete; and various people who are connected to all of them. The narrative shifts back and forth in time, telling stories of immigration, wandering, childhoods and first marriages, but the timelines eventually draw together as Hurricane Ike heads for the Texas Gulf Coast.

From firsthand experience of south Texas and its communities, Garza immerses her readers in sensory details, and draws a sharp portrait of an often-overlooked community, focusing her lens on the working-class neighborhood where most of her characters live. Evocative and sometimes heartbreaking, The Last Karankawas is a love letter to the Galveston most tourists never see and a tribute to the people who sustain, and are sustained by, their adopted homeland. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams

| Publisher: | St. Martin's Griffin | |

| Genre: | Women, Romantic Comedy, Family Life, General, Romance, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781250219411 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $17 |

| Now in Paperback |

by Katherine Center

Hannah Brooks is great at her job, which involves providing discreet private security for wealthy clients. But as she's reeling from her mother's death and a breakup, she gets an unconventional, totally non-discreet assignment: protecting actor Jack Stapleton from a middle-aged stalker by posing as his girlfriend. The Bodyguard, Katherine Center's warmhearted, witty ninth novel, follows Hannah and Jack as their romance goes from completely fake to maybe something real, and traces Hannah's inner journey as she begins to process her losses and move forward.

Center (What You Wish For; Things You Save in a Fire) creates a smart, hilarious narrator in Hannah, whose wry sense of humor is her prime coping mechanism. While her colleagues (gal pal Taylor; fangirl Kelly; tough-guy boss Glenn) seem at first like stereotypes, they (mostly) show their human sides later in the novel. Ditto for Jack Stapleton, rom-com hero: he's naturally adept at showing a practiced public face, but their forced closeness means Hannah gets to see the real Jack, whether it's his habit of leaving his dirty laundry all over the floor or his unresolved grief after the death of his younger brother. As they spend time at Jack's parents' ranch outside Houston, Hannah finds herself falling for both Jack and his family, all while reminding herself that this new life is temporary. Or is it?

With a breezy narrative style and a charming Texas setting, Center's novel will capture readers with its wit, insight and surprising ending. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams

| Publisher: | Algonquin | |

| Genre: | General, Romance, Literary, Historical - American, Fiction, Historical | |

| ISBN: | 9781643753898 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $17.99 |

| Now in Paperback |

by Louis Bayard

Before Jacqueline Bouvier became that Jackie, she was a young socialite with journalistic ambitions, who caught the eye of then-congressional member Jack Kennedy. Louis Bayard's 10th novel, Jackie & Me, is an engaging yet melancholy account of Jackie's friendship with Lem Billings, whom Jack asked to court Jackie on his behalf.

Bayard (Courting Mr. Lincoln) begins his narrative in 1981, as Lem looks back 30 years to the summer when he and Jack met Jackie. In extended flashbacks, Lem describes his friendship with Jack (dating back to their days at prep school) and his role in the swirl of Kennedy family chaos. Jackie, meanwhile, comes off as fresh-faced and kind, uncertain of her direction but longing to find meaningful, exciting work. As she and Lem spend time together on Sunday outings, which range from visits to art museums to the circus, both of them gradually realize that Jack may become Jackie's life's work, though at greater personal cost than she expects.

Bayard deftly portrays the classism of high society in the 1950s; the competing snobberies of Jackie's mother and Jack's father are particularly well-drawn. He hints that Lem was gay but never discusses it too openly (as, indeed, was the case for Lem in real life). His characters often speak in elegant riddles, and the narrative drama rides largely on what goes unexpressed: namely, Lem's deep love for Jackie and the complicated affection they both harbor for Jack. Bayard's novel provides a fresh take on an enigmatic icon and shines the spotlight on a man who built his life around being the loyal friend. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams

| Publisher: | Penguin Books | |

| Genre: | Mystery & Detective, Amateur Sleuth, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9780593299418 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $18 |

| Now in Paperback |

by Richard Osman

Four septuagenarian sleuths, an ex-KGB agent and a Swedish assassin combine for a rollicking good time in The Bullet that Missed by Richard Osman (The Man Who Died Twice; The Thursday Murder Club). The residents of Coopers Chase, a luxurious English retirement village, now have several solved crimes under their belts. But Elizabeth, Joyce, Ibrahim and Ron have not yet sated their curiosity, so at a Thursday Murder Club meeting they decide that they're going to investigate a cold case: the death of journalist Bethany Waites.

Bethany's car went off a sea cliff a decade ago, and she hasn't been seen since. Although there was blood and clothing in the car, her body was never found. Because Bethany was investigating a huge tax fraud ring just before her disappearance, the four sleuths are suspicious. Meanwhile, Elizabeth, a retired MI6 agent, has been receiving mysterious text messages that lead her to reach out to Viktor, an old KGB acquaintance. Inevitably, hijinks ensue. Game show hosts, crime bosses, television news presenters and antiques dealers are soon all drawn into the Thursday Murder Club's sphere of influence.

Laugh-out-loud funny, while also showcasing a depth and tenderness about aging, The Bullet that Missed is the delightful third entry in the Thursday Murder Club series. Osman presents a wonderful array of characters who engage in an entertaining and twisty mystery. The Bullet that Missed, heartwarming and hilarious, is perfect for readers who miss Mrs. Pollifax or Miss Marple. --Jessica Howard, freelance book reviewer

| Publisher: | Picador | |

| Genre: | Women, City Life, Literary, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781250867179 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $18 |

| Now in Paperback |

by Sloane Crosley

Cult Classic is an inventive, fantastical comic novel with decidedly modern preoccupations, among them wellness, social media and hipster-cool. But Sloane Crosley (I Was Told There'd Be Cake; How Did You Get This Number) simultaneously explores one of fiction's most traditional themes: the trials of romance, which narrator Lola suspects "may be the world's oldest cult."

Lola, who is engaged to glassware artist Boots, works at Radio New York, "a glorified content aggregator," where she's grudgingly "covering the culture instead of creating it." Outside the Chinatown restaurant where she's enjoying one of her regular Friday dinners with former colleagues from a now-defunct magazine, Lola bumps into an ex-boyfriend. The next night at the same restaurant, she bumps into another ex. By her third seemingly random encounter with an ex, Lola knows something's up. But what?

Crosley's second novel, following The Clasp, contains several items on a sci-fi thriller's ingredient list: mind control, ghosts, a feat of physical daring and a race against the clock. (Will Lola get everything sorted out before Boots returns from a trip to San Francisco?) And yet Cult Classic never strays from rom-com territory, with longtime serial dater Lola routinely lamenting her checkered history with dodgy men: "I went out with them anyway, these bouquets of red flags." As ever, Crosley is reliably funny as well as winningly piquant with her characters' observations. Says Lola at one point, "The love lobby is worse than the gun lobby. More misery, more addiction, more heads on spikes." --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

| Publisher: | Atheneum | |

| Genre: | Adolescence & Coming of Age, Girls & Women, Social Themes, Activism & Social Justice, Juvenile Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781534496262 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $17.99 |

| Starred | Children's & Young Adult |

by Joy McCullough

In Code Red, a stirring and thought-provoking middle-grade novel by Joy McCullough (Across the Pond; Enter the Body; Not Starring Zadie Louise), a privileged but lonely teen's eyes open to issues of social inequity and period poverty.

It's "no secret" that 13-year-old Eden's family is rich, although she would prefer a warmer family life over her "cold and lonely" fancy house. Eden's parents are divorced; her father is a pilot, and her mother is a high-powered CEO of one of the biggest menstrual product companies in the world. A growth spurt and an injury end Eden's elite gymnastics career, forcing her to give up online school and start "regular-kid school." Getting suspended for accidentally injuring a boy who was teasing her about her mother's presentation at their school's career day doesn't exactly help her stay under the radar. It does, however, lead to her spending her suspension week at a food pantry and resource center, where Eden learns that many people don't have access to menstrual supplies for reasons like poverty or homelessness. Eden joins forces with a creative and diverse group of people working to build political, corporate, and public support for an initiative financing menstrual products in schools and other public places. Feeling the urgency of the issue, Eden is galvanized to push back against her tense and defensive mother's resistance and create a social media campaign featuring the hashtag Code Red.

With themes of social justice, classism, trans awareness, and family pressure, Code Red is likely to enlighten, delight, and maybe even inspire middle-grade readers, menstruators and non-menstruators alike. --Emilie Coulter, freelance writer and editor

| Publisher: | Sourcebooks Fire | |

| Genre: | Dystopian, Girls & Women, Social Themes, Young Adult Fiction, New Experience | |

| ISBN: | 9781728260006 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $11.99 |

| Children's & Young Adult |

by M Hendrix

In M Hendrix's compelling, vivid dystopia, The Chaperone, 17-year-old Stella struggles with the near-total domination of women in a society where the Minutemen party controls everything, "from the top branches of government--liberty and security--all the way down to the military constables."

In New America, unmarried females who reach puberty must be supervised by a chaperone at all times; they are not allowed romantic relationships, a college education, or careers--only marriage and "babies right away." When "golden-brown"-haired Stella's beloved chaperone, Sister Helen, dies suddenly and mysteriously, she leaves Stella a cryptic message: "Angel." Her new chaperone, Sister Laura, is unusual: Stella is allowed to jog with her usually off-limits dad, take self-defense lessons, and read banned books. These freedoms at first feel terrifying but quickly become liberating. Sister Laura even allows her to spend time alone in public, which Stella and her female classmates are told is exceptionally dangerous due to supposed kidnappings of unchaperoned young women in public. The more independence Stella gains, the more she questions--by the time she figures out "Angel," she knows it is essential she escape.

Hendrix's first work of fiction presents an infuriating, nonsensical diminishment of women that turns them into helpless children and baby-bearers. With its shades of Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale, The Chaperone depicts a New America that feels all too real. Hendrix's storytelling is first rate: characters develop believably, and the action builds dramatically to a satisfying conclusion. A strong, rewarding contemporary vision of oppression. --Lynn Becker, reviewer, blogger, and children's book author

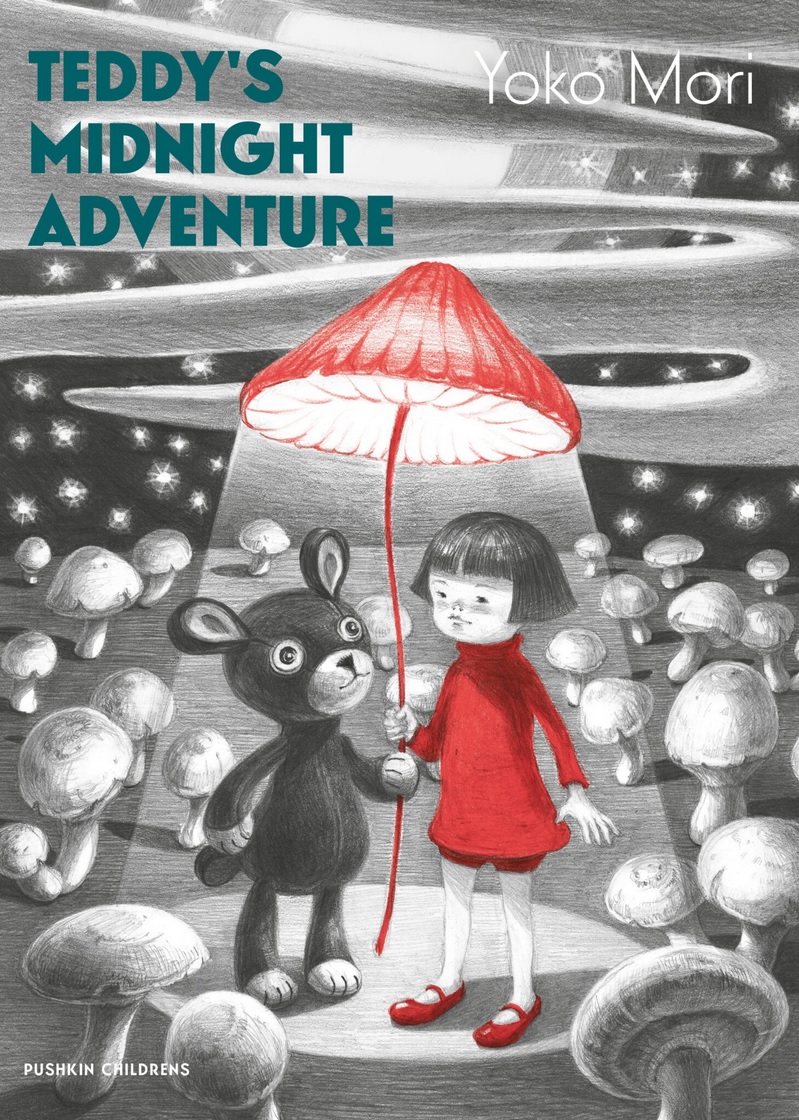

| Publisher: | Pushkin Children's Books | |

| Genre: | Toys, Dolls & Puppets, People & Places, Asia, Bedtime & Dreams, Juvenile Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781782694014 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $19.95 |

| Children's & Young Adult |

by Yoko Mori, trans. by Cathy Hirano

In the enchanting, ethereal Teddy's Midnight Adventure, one young girl and her stuffie experience the magic of a moonlit night as they search for Teddy's lost eye.

Akiko and Teddy are playing outside until Akiko's mother calls the girl in. That's when "Teddy's eye pop[s] off and sail[s] through the air." Akiko searches, but the eye doesn't turn up. She lovingly wraps a bandage around Teddy's head and wishes she was "as small as Teddy" so she might "walk under the grass and look for it." That night, Akiko wakes to find that she is indeed very small. She leads Teddy outside and they hunt for the eye, though at first, it's nowhere to be found. The "trilling" bell crickets, Mee-chan the cat, and sleeping Mrs Crow are no help, but after a sudden rainfall Akiko and Teddy find toadstools, "balloon-like" puffball fungi, and "a forest of glowing mushrooms." By the light of these magical lamps, Akiko spots Teddy's eye. When she wakes the next morning, Akiko is "back to her normal size," and Teddy's eye is "back on his face, just like always."

Yoko Mori's story depicts what could be any child's dream: a post-bedtime adventure that transforms the comforting realm of the everyday into fantasy. Hirano's gentle translation fully expresses the magic and sweetness in Mori's picture book. Detailed gray-scale illustrations feature pops of red to highlight Akiko's clothes and the wonderful glowing mushrooms. The intricate, accomplished, often whimsical art fills Mori's nighttime world with glamour. --Lynn Becker, reviewer, blogger, and children's book author

| Publisher: | Walker Books US | |

| Genre: | School & Education, Mathematics, Girls & Women, Juvenile Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781536218022 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $19.99 |

| Children's & Young Adult |

by Marissa Moss, illust. by Marissa Moss

A sixth-grader applies problem-solving skills to the complex world of middle-school friendships in Talia's Codebook for Mathletes, a direct and insightful STEM-centered illustrated novel from Marissa Moss.

"Middle school is tricky." When Talia Zargari is blindsided by a friend-breakup with neighbor Dash, she applies her book-smarts to reading people. After all, as Talia deduces, "Middle school isn't about learning stuff from teachers and books. It's really about learning how to get along with other people." By thinking of friendship as a logic problem, Talia uses "non-math codes" to "understand a social situation." Her attempts to identify "that mysterious something that makes a person 'likeable' " help Talia highlight her own strengths and find solidarity among her peers.

Moss's signature, simple illustrative style and choice of the notebook journal format may feel familiar to fans of her prolific Amelia's Notebook series. Full-color ink, watercolor, and gouache sketches on a pale blue-gridded background depict Talia's inner musings and social interactions, with speech bubbles showing dialogue. Talia makes 49 Observations and nine Deductions that divide the book into short chapters, all interspersed with puzzles, quizzes, and codes to produce a dynamic and casually instructive format. A note explains Moss's personal connection to Talia's gendered mathlete experience.

One empathetically offbeat tween solving one relatable middle-school dilemma adds up to a wholly entertaining STEM story. --Kit Ballenger, youth librarian, Help Your Shelf

| Publisher: | Rocky Pond | |

| Genre: | Alphabet, Concepts, Body, Size & Shape, Juvenile Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9780593530467 | |

| Pub Date: | June 2023 | |

| Price: | $18.99 |

| Children's & Young Adult |

by Corinna Luyken

Corinna Luyken (The Tree in Me) invites children to move their bodies while exploring the alphabet in ABC and You and Me, a playful, vigorous appeal to wriggle, twist, bend, point, and more in the name of imitating alphabet shapes. Luyken kicks things off by posing direct second-person questions that engage readers with their immediacy: "Can you wiggle your wrists?" Most spreads are wordless and feature people, all clad in white clothing, creating the letters of the alphabet with their bodies; each person is accompanied by an object beginning with that letter. (A key in the backmatter lists the objects.) Luyken occasionally pauses for rhyming text that celebrates not just limbs that stretch, move, and bend but also various places on the body: the belly, ankles, fingertips, nose.

Spotlighting abundant body positivity and diversity in these characters, Luyken's pencil, watercolor, and ink illustrations depict people, young and old ("From the biggest all the way down to the littlest"), with varying skin tones (and tattoos), ethnicities, body sizes, and hair styles, colors, and textures. She also demonstrates diversity in ability: there are wheelchair users, a child with orthopedic braces and crutches, a person wearing an insulin pump, and someone with a hearing aid. Luyken's graceful, flowing lines and subdued pastel colors bring a softness and warmth to the whole body-bending adventure. Learning the alphabet was never so spry. --Julie Danielson, reviewer and copyeditor