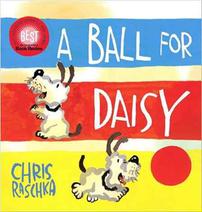

On Monday in Dallas, the 2012 Caldecott Committee awarded Chris Raschka's A Ball for Daisy (Schwartz & Wade/Random House) its top prize. The picture book stars a dog named Daisy who lives in the moment, an apt heroine for a book creator whose artwork exudes spontaneity.

On Monday in Dallas, the 2012 Caldecott Committee awarded Chris Raschka's A Ball for Daisy (Schwartz & Wade/Random House) its top prize. The picture book stars a dog named Daisy who lives in the moment, an apt heroine for a book creator whose artwork exudes spontaneity.

Congratulations!

I'm thrilled of course! I'm totally unprepared for it, unaware and all those things.

In your interview on NPR Monday, you said the inspiration for A Ball for Daisy came when your son, then four, lost his ball to a dog. Many of your books deal with a mood or feeling. Does it take time to figure out how to convey that elusive quality?

They do often begin with a particular emotion at a particular time. Finding out how to put it into book form can take a long time. In this case, it took many years. I did make the initial dummy right around then. It's quite similar to what we ended up with, but initially I had only Daisy, so you'd just see hands coming in from the side or from above, and then slowly I brought in the girl who owns Daisy. I think that made it more concrete.

We see the world as Daisy does, full of feet and hydrants and the lower trunks of trees.

That was always my intent, to push the grownups and people up high or away, and keep it centered on the viewpoint of a little dog. Sort of incidentally, in retrospect, when I introduced the idea of a new ball, I realized that dogs are colorblind. Maybe I should have done this book in black-and-white.

I think at that time [while working on Yo! Yes?] the notion of a wordless book was in my mind. When I decided to do this particular idea from the point of view of a dog, it made sense to keep it wordless. A wordless book has its own challenges, especially challenges in pacing and movement. I always had in the versions I'd done some full spreads, some vignettes, but my original version had more spreads. Lee Wade suggested I put in a few more moments.

We loved the eight-panel spread of Daisy's meltdown after the ball bursts.

Ah, "the stages of grief" page. That was always for me the lynchpin of the book. That's always been in the book from the beginning.

You've tackled many different topics, but your artwork consistently maintains a feeling of spontaneity. How do you do that? We saw no pencil marks.

There are no pencil marks, not that there's anything wrong with pencil marks, but it is completely immediate. I do a lot of what my friend Vladimir Radunsky calls "rehearsing." I rehearse it and rehearse it and then do the finished work. It's kind of a mental trick I have to play on myself. Sometimes I think I should use really cheap paper. Oddly enough, if I don't use really good watercolor paper, oftentimes I fake it. Watercolor paper does help focus my attention. That's not to say I don't throw out a painting. I did a book called Fishing in the Air by Sharon Creech. I painted the same picture on the front and the back of each piece of paper. And it got me a little more relaxed. Sometimes when I sketch, I do four paintings of the same thing at the same time. You have to let it be loose and know you'll throw away three-quarters of them.

It looked as if you used ink only for Daisy's eyes, nose, mouth, paws and collar. Did you ink those in first? Or do you start with watercolors and then ink in?

The ink comes last. First is this wet on wet. Then the gray that is Daisy and the girl and some other elements. That's Chinese ground ink, which is kind of soft and sometimes brownish or bluish. Then the other color moments. The last thing is the heavy opaque--either the red of the ball or the black of Daisy's mouth and eyes and collar. I consciously try to paint with all parts of the brush at once, so the tip and the fat part of the brush are doing valuable work at all times. I so often forget that. I so often focus on the tip and think, "I'll fix what's going on at the other end of the brush later." But if I really focus on the whole brush at once, that's when it really works. I'm doing a book right now for Robie Harris, and I'm using oil crayons. I'm trying to get myself to use them the same way I use a brush.

Do you have a dog?

I grew up with dogs, but I don't have one now--I'm not sure I want that getting out. I love lurking at the edges of a dog run. The real model for Daisy I saw come into a bar on 104th Street, very much like Daisy but a little scruffier. She cracked me up, that dog that day. The first Daisy was brown, but this dog that walked into the bar was white.

Do you like the structure of a 32-page picture book?

That's the great thing about picture books. You have a structure and you can push at the boundaries. If the boundaries are gone, it can deflate. It's like the three-minute song. I think that's why poetry so often works well with picture books. Poems are very heightened, usually a single emotion or a single idea that's conveyed or made vivid in 32 pages or 14 lines.

It's interesting that you released Seriously Norman!, your first novel and your book with the most words, the same year that you released A Ball for Daisy, your first book with no words. Were you working on them both at the same time?

Yes, in fact, very much at the same time. Doing the novel is a whole new world for me, but in some ways it's similar in the shaping. It's just with a novel you have to read the whole thing to see the shape of it. With a picture book, you can lay it all on the floor. In other ways, I think it's easier. There's only one way to write the word "dog" and there are so many ways to paint a dog. --Jennifer M. Brown