Sourcebooks children's editor Steve Geck writes:

Sourcebooks children's editor Steve Geck writes:

One day in a bookstore I picked up The Funeral Makers simply because of the title. Reading the flap copy convinced me to buy it. It's one of the best purchases I ever made because I discovered the world of Cathie Pelletier. I'm not alone in my appreciation for Cathie's works; Wally Lamb, Fannie Flagg, Richard Russo, and Matthew Sharp have all showered her with praise. But I may be the only one who's stalked her. I tracked down her mailing address on the Internet and wrote her a fan letter. Rather than requesting me to cease and desist, she wrote back the nicest e-mail, and we struck up a correspondence that's continued for 10 years.

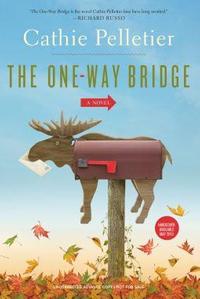

When I joined Sourcebooks a little over a year ago, I was so focused on my work as an editor of children's books that I was oblivious to the fact the Landmark imprint was publishing Cathie's first novel in almost a decade. Attending the spring 2013 sales conference and hearing that The One-Way Bridge was being released in May was one of the happiest moments in my time at Sourcebooks. So when I was given the opportunity to ask one of my favorite authors some questions about her newest novel, I jumped at the chance.

The One-Way Bridge is set in Mattagash, a small, fictional town in northern Maine. Where did the inspiration come from?

The One-Way Bridge is set in Mattagash, a small, fictional town in northern Maine. Where did the inspiration come from?

I was born and raised in the northern Maine town of Allagash, on the banks of the St. John River. Find Fort Kent on a map. Then go southwest about 30 miles. Sometimes Allagash is on the map and sometimes it's not.

You do a terrific job of drawing out the quirks of each of your characters--like Florence Walker's Word for the Week and Orville and Harry's mailbox feud. Are any of your characters based on people you know?

No. Or maybe I'm Florence in 10 years? I think the only similarity is that every town has its gossips and ne'er-do-wells. So folks here like to find real people in my characters. But even if I started with a real person, the character often takes over and creates his or her own life. The only comparisons would be in those general terms of gossips and scalawags.

The Mattagash community is as isolated as a town can get but the people remain fiercely connected. What were some of the challenges you faced in building this setting?

In a town this small, and at the end of a road, people have no choice but to be connected. And sometimes it gets fierce! In a sense, any town is a microcosm of a city. In a city, most residents get up, take the same route to work, talk to the same people at the same deli, or on the train or bus. They work with the same people and then come home to the same family and friends. People in the city sometimes live in small towns they have built around themselves. The challenges for my Mattagash books, for me as a writer, are the limitations. Characters can only act and react to what is in their environment. They can talk about a New York subway, but they can never take one unless they leave Mattagash. So I'm limited by their limitations. This is why I started writing novels in between the Mattagash books that have a larger canvas and setting.

What was your inspiration behind the town's one-way bridge? Why did you place such a strong focus on this particular landmark?

I grew up in a town with three one-way bridges. I spent time as a child near the Allagash River Bridge, which is where my grandfather lived. He ran the ferry there across the river for 37 summers until the bridge was built in 1945. Later, when a bad ice jam on the rivers took out all three bridges, I was watching this news from Nashville, Tenn. It was then that I realized I had grown up with a metaphor for life right under my nose and had never used it before. But three one-way bridges in a novel would be too many. So, like the ice jam, I took two of them out.

One of the main characters, Sgt. "Harry" Plunkett, suffers from flashbacks from his tour in Vietnam. How did you manage to make his memories seem so vivid and genuine?

First of all, I didn't want him to have flashbacks, but characters often take a writer into unknown territory. So I began reading accounts by Vietnam vets on the Internet. Many months of reading. But I didn't want to take anything from there since I wanted Harry's memories to be his own. So I simply imagined how he felt and what he did. That is the writer's job. But by this time, so late in the novel, I'm pretty much recording what the characters tell me. It wasn't an easy task, but imagine what it must have been like for those real soldiers.

How do you balance the humor in your novels with the more dramatic story lines?

In many ways, it's the sense of humor I grew up with here in Allagash. Everyone is funny. (Thank God they don't all write novels.) There is a very Irish vein of humor here since many people have Irish ancestry. (My mother was an O'Leary.) I just started writing that way naturally. It's funny, even to me, and then you turn a corner and suddenly it's not funny anymore. Humor should have a sad underbelly. Otherwise, it's just a slip on the banana peel.

What do you hope readers will learn or take away with them from your book?

What do you hope readers will learn or take away with them from your book?

I think everything I write has the same message, that we're all just human beings doing our best while affected greatly by our environments. But maybe younger readers will examine the Vietnam War, possibly for the first time. It's certainly not my area of expertise, but I learned a lot more about it now than when it was actually happening. But wars are like that. They're like divorces. You only figure out what went wrong years after they're over.

Are there any occupational hazards to being an author?

I have no children so that solves the Big One. It must be tough being a good and attentive parent while writing a novel. My husband waves a hand in front of my eyes when he wants me to pay attention to what he's saying. Having rescued animals is enough parenting for me. Writing isn't something you can learn, or be taught. (You can be given direction if you have talent to begin with, but that's it.) So I guess the hazards are so much a part of my psyche that I don't notice them. Being from and writing from a small town had its pitfalls at first. After a few books, I think folks realized that I wasn't writing about real people. There are so many tough, back-breaking jobs out there in the real world (construction, woods work, waitressing at the diner) that I have no right to sit at a computer and talk of hazards.

If you could be any hero or heroine from a novel, who would it be and why?

Dorothy, in The Wizard of Oz. That was the first novel I read, along with Charlotte's Web, which made me cry for a year. So I wouldn't want to be Charlotte. She dies. But imagine getting out of dusty Kansas for such an amazing adventure, only to realize, "There's no place like home." I'd even wear those ruby shoes.

If you could work with another author, who would it be and why?

I love the authors who make me laugh. But again, the humor has to come with a sad underbelly. But if I had my choice of any writer? Let's go way out on a limb here and choose someone dead. William Shakespeare. Can you imagine working near someone like that, let alone with him? I'd bring him coffee, make his lunch, wash his socks. I've just read that he smoked pot, so I'd probably be cleaning a lot of ashtrays, too.

You spent many years in Nashville working in the music business as a songwriter. Is it true David Byrne of Talking Heads recorded one of your songs?

Yes, a song I co-wrote called "Who Were You Thinkin' Of." I'm not sure it ever made an album, but he used to perform it live all the time. There are clips on the Internet of him with Richard Thompson doing the song. They were in some church, if I remember correctly.