Boxers and Saints may be purchased separately, but for maximum appreciation of Gene Luen Yang's extraordinary achievement with this "graphic diptych," they must be read together.

Boxers and Saints may be purchased separately, but for maximum appreciation of Gene Luen Yang's extraordinary achievement with this "graphic diptych," they must be read together.

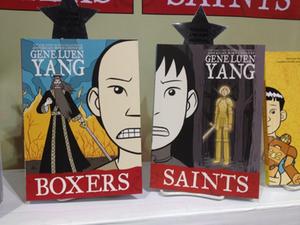

Yang (American Born Chinese) tells the story of China's Boxer Rebellion through the perspectives of two young people on opposite sides of the conflict. Both are born into family circumstances that would hold them back, but the Boxer Rebellion offers them both unexpected opportunities. Boxers ($18.99 paper, ISBN 9781596433595) unfolds through the eyes of Little Bao, the third of three sons living in 1894 Northern Shan-tung Province, while Four-Girl--the only one of four daughters to survive past a year--guides readers through Saints ($15.99 paper, ISBN 9781596436893). Their paths criss-cross in the two books. It's a brilliant approach to any conflict, but especially one as complex as this.

While his big brothers gamble, Little Bao watches opera performances in his village, and honors Tu Di Gong, the local earth god, at the entrance to the stage. Though illiterate, Bao learns the history and legends of China through operas about the Monkey King, the God of War and the Lady in the Moon. When a thief steals from the market, Bao's father punches him, and the thief brings back a Catholic priest (a European "white devil") to mete out his justice. It's a microcosm of the larger misunderstanding taking hold in China, and it leads to greater violence and a shattered Tu Di Gong. Yang demonstrates that while each side insists that it's right, there's no room for both belief systems.

For Bao, the arrival of the Europeans leads him to Red Lantern, an expert in the martial arts, and Bao ascends within the Brother-Disciples of the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist. The Brother-Disciples become the chief defenders of the powerless peasantry. As they fight, Yang's graphic novel sequences chart their metamorphosis into the deities Bao knows through his love of opera; peasants transform into gods, like Clark Kent to Superman. It is a conversion born of catastrophe. Similarly, in Saints, Four-Girl discovers a kindness among the Christians that she doesn't find at home (where her grandfather considers her a bad omen). In a moment of great desperation, she sees a vision of Joan of Arc.

|

|

| photo: Jarrett J. Krosoczka | |

Crossover appearances between the two books convey a larger historical context. The thief from Boxers, called an "opium fiend" by a converted Chinese Catholic in Saints, responds, "Both your religion and my opium come from the hairy ones [the white devils]! It's ridiculous that you use one to judge another!" Yang alludes to the earlier Opium Wars, and the whites as carriers of opium as well as Christianity. And Bao's fantasy of marrying Four-Girl in Boxers (their chance meeting also appears in Saints) makes their later meeting all the more wrenching.

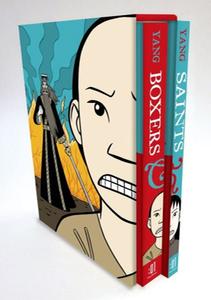

In both books, Lark Pien's use of color in an otherwise earth-toned palette causes the deities to rise from the pages of Boxers and casts a golden glow on Joan of Arc in Saints. Pien endows each book with its transcendent quality and honors the beliefs showcased in each book. Even the way their front covers and spines line up, in a brilliant feat of design, underscores the fact that there are two sides to this complex story, each deserving of a hearing. --Jennifer M. Brown

Shelf Talker: National Book Award finalist Gene Luen Yang takes an ingenious approach to the 19th-century Boxer Rebellion in China, through two protagonists, one a leader of the peasantry in Boxers, the other a newly converted Catholic in Saints.