Charlie Parker's tragic story has been told before, perhaps most memorably in the 1988 movie Bird, directed by Clint Eastwood and starring Forest Whitaker, but Crouch's version is as much about the birth of modern jazz and "Negro" (Crouch's usage) history as it is about Parker. The southwest jazz circuit at the time featured nearly all the giants who at some point earned their chops in Kansas City. To hear Crouch lovingly describe Bill Basie and Lester Young or Hot Lips Page and Jimmy Rushing is to be there at a smoky table in Lena's club on 18th Street. He can be forgiven if this enthusiasm produces prose that sometimes gets away from him, as in this description of a typical after-hours cutting competition: "Chu Berry came through Kansas City and pushed his foot through the bell of his tenor and up the butts of the roughest men in town."

The Charlie Parker of Kansas City Lightning is "lean as a telephone wire" and overwhelmed by his mother, Parkey, who raised him in a tough neighborhood. He doesn't care much for school (Crouch quotes him as saying, "I went in as a freshman, and I left as a freshman"); when it comes to learning to play like Roy Eldridge on trumpet or Buster Smith on alto, he schools himself. While Crouch spends considerable time describing Parker's young romance with Rebecca Ruffin and their marriage, parenthood and separation, the real romance of his early life came on the dark streets, where Kansas City provided plenty of dope, women and booze to musicians who could see "the high and mighty get low down and dirty, the low down and dirty get high and mighty... and [see] what women might do for the excitement of experiences with... these colored fellows who appeared free and drifting on a cloud of glamour, gifted with the ability to shape moods with sound."

This romance with "the life" may have ultimately brought Parker down, but that is for Crouch's second volume. In Kansas City Lightning, Bird is still working at his music, moving up the jazz ladder and making his mark... all in the place where "the blues got shouted, purred, whispered, and cried in such inventive style that the city became the third great spawning ground for jazz after New Orleans and Chicago." Apparently, in the case of Kansas City and its jazz stars, lightning struck 18th Street more than once. --Bruce Jacobs

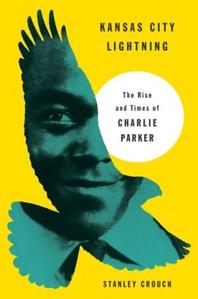

Shelf Talker: This first volume in the epic biography of Charlie Parker showcases Stanley Crouch's encyclopedic knowledge of jazz history and effusive prose.