In a New York City bookshop where much of the action occurs in Sheridan Hay's 2007 novel The Secret of Lost Things, the staff is adept at a game called "Who Knows?"--pooling their varied and idiosyncratic skills to answer otherwise unfathomable book requests, including the customer whose "hands might move apart, as if to say 'it's about this thick'... [T]he only reliable source of reference was the staff and their collective memory."

In a New York City bookshop where much of the action occurs in Sheridan Hay's 2007 novel The Secret of Lost Things, the staff is adept at a game called "Who Knows?"--pooling their varied and idiosyncratic skills to answer otherwise unfathomable book requests, including the customer whose "hands might move apart, as if to say 'it's about this thick'... [T]he only reliable source of reference was the staff and their collective memory."

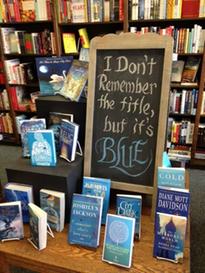

We know the drill. What prompted my recollection of the "Who Knows?" game was a bit of clever sales floor merchandising recently at Blue Willow Bookshop, Houston, Tex. A photo posted on Facebook showed their "Blue Display," featuring a slate on which the following words, all-too-familiar in their infinite variations to booksellers worldwide, were written: "I don't remember the title, but it's blue."

What prompted my recollection of the "Who Knows?" game was a bit of clever sales floor merchandising recently at Blue Willow Bookshop, Houston, Tex. A photo posted on Facebook showed their "Blue Display," featuring a slate on which the following words, all-too-familiar in their infinite variations to booksellers worldwide, were written: "I don't remember the title, but it's blue."

This sparked my memory and a little research. I recalled that Blue Willow's owner Valerie Koehler had mentioned a few years ago (also in 2007, as it happens) that while she'd been giving a lot of thought at the time to online searching as it related to the game, she believed a discerning human element was absolutely critical. She trained her staff to field vague title requests with a healthy dose of well-masked skepticism.

"When searching, use unique keywords, ask leading questions," she advised. Assume, without letting your customers know it, that they might be just a little confused or misinformed. She cited the example of someone who'd been reading a great book, wanted additional copies for friends, and described it as "a memoir with 'I Remember' in the title, in which a retired man is dying and telling his life story and he was a historian and he studied war and he lived on an island." Using these clues, Koehler had "gently" enlightened the customer that she was actually reading Rules for Old Men Waiting, a novel. Result: pleased customer and two books sold.

We've all been there, finding infinite ways to merge available technology with a bookseller's ability, instinct and well-honed memory. It's reassuring that humans can often still reign supreme in the realm of "blue cover" inquiries. Social media helps now, of course; I often see "calls for a title" on Twitter and Facebook as booksellers crowdsource in a digital version of the "Who Knows?" game.

Same as it ever was? Absolutely. In 1936, George Orwell described "the other dear old lady who read such a nice book in 1897 and wonders whether you can find her a copy. Unfortunately she doesn't remember the title or the author's name or what the book was about, but she does remember that it had a red cover."

Despite my occasional suspicions, I don’t really believe people consciously make up their endless stream of misheard, misread or misremembered titles. On the other hand, I did unearth a condescending New York Times piece from 1909 that featured the Office Philosopher and the Office Radical setting out to test the mettle (aka belittle) local booksellers after this exchange:

Their bookish quest begins when the Philosopher shares a joke "told by a book clerk to the effect that somebody went into a bookstore and asked the long-suffering clerk for a copy of John Stuart Mill on the Floss. Now I consider that a high-class joke."

Unamused, the Radical says he has "read a bushel of these jokes at the expense of the bookshop customers... and I'll bet they are fakes. For this reason: not one-tenth of the clerks in bookstores would know the difference. If a customer went into a book store and asked for a copy of John Stuart Mill on the Floss, it would be dollars to donuts that the clerk would reply, 'We haven't got it in stock, but we can order it for you.' " The two gentlemen wager dinner and then proceed to stump and humiliate bookseller after bookseller in the city.

Seeking balance in my bookselling universe, I soon discovered another NYT piece, from 1914, in which the death of one of the founders of Leggat's Bookstore was noted, followed by an observation that the shop's clientele included "all the famous literary and public men of his era. But they also included many thousands who had no fame but knew where books could be got for the most reasonable price and where they could be quickly served by clerks who knew something about every book that was ever published."

Take that, Philosopher and Radical. Leave them "clerks" alone. By the way, they're called booksellers, and one of the best parts of this vocation is the opportunity to serve as "customer request decoder," a mystifying, Holmesian task in which clues are presented and deductions made, elementary and otherwise. --Robert Gray, contributing editor