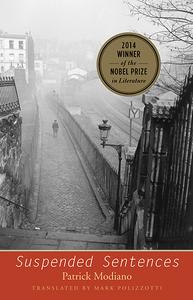

Mark Polizzotti is an author, editor, translator, reviewer and head of the publications program at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. His books include the collaborative novel S., Lautréamont Nomad, Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton, Luis Buñuel's Los Olvidados and Bob Dylan: Highway 61 Revisited. His articles and reviews have appeared in the New Republic, ARTnews, the Nation, Parnassus, Partisan Review and elsewhere. He has been an editor at Random House, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, David R. Godine and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. And he has translated more than 40 books from the French, including works by Gustave Flaubert, Marguerite Duras, Raymond Roussel, André Breton, Jean Echenoz--and Patrick Modiano, who earlier this month won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Polizzotti's translation of Modiano's Suspended Sentences: Three Novellas is being published by Yale University Press next month. Here George Carroll, independent publishers rep and Shelf Awareness world literature editor, asks some questions about Modiano, the art of translating and more.

When you were translating Suspended Sentences, did you imagine that Modiano would become a Nobel Laureate?

No, and it's just as well: I might unconsciously have layered on a bit too much grandeur. Let's say I was pleasantly surprised. Not that I don't feel he deserves it--far from it. But Modiano is not a writer of grand gestures, as some previous laureates have been. His work doesn't aim for the international sweep and journalistic earnestness of a Le Clézio, for instance, and certainly not the grandstanding philosophical aggressiveness of a Sartre (or even of a Camus, though Modiano's and Camus's writings often share a certain modesty of tone). There is an understated, almost matter-of-fact quality about Modiano's books that makes them very strong--a quiet strength--but that doesn't necessarily attract the notice of big prize committees. (That said, his work has won virtually all the major French literary awards, including the Goncourt.) I was surprised when I heard the news the way I was surprised when Elfriede Jelinek won--another author whose work stands outside the mainstream, and, as it happens, another whom I'd published, back when I was an editor at Weidenfeld & Nicolson (we did her first book in English, The Piano Teacher, which was later made into a film).

At the same time, let's not forget that the main subject underlying virtually all of Modiano's work is the greatest historical calamity and human tragedy suffered by France (and not just France, of course) in the 20th century: the Second World War, not only for the overt horrors it visited on so many lives, but also--and in some ways even more so--for the insidious moral devastation of the Occupation, the troubling questions it continues to raise even today. This is the stain that permeates his narratives, whether they take place during the war years or, as is more often the case, in the decades following. Still, these questions don't necessarily mean the same thing to people born several generations after the fact, and I believe that it's the indirect way Modiano addresses them--in the ambiguous choices his characters make or don't make, the way they drift into the most equivocal situations (as with the protagonist of Lacombe Lucien)--that makes his books relevant to contemporary audiences.

Did you work directly with Modiano on the translation? Is he fluent in English?

Did you work directly with Modiano on the translation? Is he fluent in English?

Modiano had little to do with the translation itself--I believe Yale sent the manuscript to him when it was done, and I'm told he's pleased with it--but he did answer a few questions about specific details, personal references that I wasn't sure I'd gotten right, and provided a few pieces of information that I needed for my introduction. Having written to him through his publisher, I received a cordial, extensive, handwritten letter, which I thought was very gracious of him. Overall, however, we haven't had any contact to speak of, though I'd love to meet him at some point.

Were the three novellas previously translated into English? If so, did you read them or dive right in?

No, this is the first time these three have been translated. About 10 books of Modiano's have been published in English, out of nearly three dozen that he's written, and I had read most of the ones previously translated well before undertaking the ones for Yale, so I had a general sense of how Modiano might sound in English (even though nearly every book was the work of a different translator). I have retranslated books that had previously been done in English--Flaubert's Bouvard and Pécuchet and Raymond Roussel's Impressions of Africa--but in both those cases I made a point of not reading the other translations beforehand so as not to be unconsciously influenced.

Where does Modiano place in the difficulty scale of the authors you've translated from the French? Were there words, phrases, colloquialisms that were a challenge?

That's a key question. People often assume that more avant-garde texts, the ones that rely on word games and verbal pyrotechnics, are the most difficult, but I usually find that it's the "simplest" writings that pose the biggest challenges. Translating the experimental ones that can be tricky, but often it comes down to re-creating the pun in a different way--of substituting cleverness for cleverness. In the case of someone like Modiano, much of the pleasure comes from the naturalness of the voice, from the keen linguistic instinct that allows him to craft sentences and dialogue that come across as absolutely spot-on--and that can be murder to get right. Because as a translator, you're trying to juggle meaning, rhythm, cultural resonance and verbal music, and somehow make it all sound just as natural in an entirely different language and context. Of course, to some extent this is a challenge that every translator faces with every text. But when dealing with a voice as seemingly straightforward and unadorned as Modiano's, which manages to say highly resonant things with great simplicity and great beauty, finding exactly the right tone and pitch in which to recreate them in English can be the hardest part.

|

|

| Patrick Modiano | |

Modiano vaulted over some odds-on favorites to win, including Bob Dylan. You wrote the 33 1/3 book Highway 61 Revisited. What's more daunting: translating from French or writing about the iconic album of the '60s?

I greatly enjoyed writing Highway 61 Revisited, probably more than I've enjoyed writing anything in my life, but all things considered I'd much rather be translating. There's a pure pleasure to translating, an experience of unadulterated craft, of unalloyed engagement with the plasticity of language. I like writing, but when you have to devote your attention to the content as well as the expression, it's a different experience. Gregory Rabassa once said that the translator can be considered the ideal writer because he doesn't have to worry about things like plot and character; since all that has already been provided, "he can just sit down and write his ass off." When I translate someone like Modiano, or Jean Echenoz, or even Flaubert and Roussel, and can immerse myself comfortably in their verbal space, I find it invigorating, challenging in the best sense, to try to re-create that space in another idiom. Sure it can be daunting: I mentioned somewhere that translating Bouvard and Pécuchet was like having Flaubert's ghost on my shoulder for a year, waiting to pounce on every deviation from the mot juste. But it's also immensely satisfying.

Did you acquire the three Modiano books for David R. Godine when you were editorial director there?

David and I were talking about this the other day. Funnily enough, he remembers that I acquired the books, and I remember that he acquired them. I do know that I worked on Honeymoon while I was an editor at Godine, which I put into our Verba Mundi translation series, and which remains one of my favorite books by Modiano (along with its nonfiction pendant, Dora Bruder). I'm pretty sure that David acquired the children's book Catherine Certitude, which he asked me to translate, though I couldn't at the time. Instead, it was done, beautifully, by the excellent William Rodarmor.

Is it true that you fell into translation by accident?

As with most good things in life, it was entirely unexpected. I've told the story elsewhere, but the short version is, I was in France at the age of 17 and found myself across a table from the experimental novelist Maurice Roche, whom I'd barely met, and the only ice-breaker I could think of on the spur of the moment was to offer to translate his book--which I'd barely understood. To my amazement, Maurice took me up on it, and inadvertently set me on my life of crime. That was 40 years ago and I still haven't reformed. There's more to it, of course, and if anyone's interested the full story is in a piece I wrote called "Memento Maurice."

You're given translation credit on the jacket of Suspended Sentences. I wish all publishers would do that. It's important, yes?

It's important not only as a mark of respect for the translator's task but also as an acknowledgment that the book you're holding in your hands is a collaboration. It's not the same as the original, but is by necessity a reinterpretation, one person's reading and re-creation of the original. There has been a lot of ink spilled over whether translation is "possible," whether reading a translation can ever approximate reading the original, how much is "lost," etc., etc. What most of these discussions leave aside is the fact that every reading is imperfect, even in the original language; that every reader, like every translator, both "loses" something in experiencing an author's work (through misunderstanding, or inattention, or personal bias) and at the same time brings something to it that no one else could. When it comes to translating, my English Modiano is no more "definitive" than Barbara Wright's, or Daniel Weissbort's, or anyone else who has translated him. Suspended Sentences is Modiano filtered through Polizzotti--though, if I've done my job, filtered in a way that lets an Anglophone reader experience Modiano's work the way a French reader would experience it in the original, with the same understanding and emotional impact. So to get back to your question after this minor diatribe, yes, it's important to identify the translator up front (for praise or blame, depending), and also to acknowledge that this edition is the product of a second writer's reinterpretation. The small literary houses and university presses, including Yale, have generally been very good about this; the larger commercial publishers, which tend to brush the book's foreign origins under the rug (when they publish translations at all), not so good.

On that score, Yale will kill me if I don't mention that it has set November 11 as the pub date--the day World War I ended, though whether that's by design or coincidence, I don't know.

You have a pretty serious day job at the Met. Do you sleep?

With enormous pleasure.