|

|

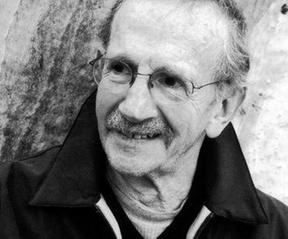

| Philip Levine | |

This week I've been thinking about winter and work. It's five below zero and the wind chill is Arctic (soon to be Siberian). The weather does its work as I do mine.

Maybe I didn't need to write about Philip Levine's death and his poems. So many people already have. But "need" is a funny old word. I have been his reader for years and admire his work, in every sense of that complex little term. So I did need to say something after all.

I often write about work. I was born into the working class (Remember the working class?). I've worked a lot of different jobs over the years at various places--golf course, marble mill, supermarkets, restaurant, magazine, bookstore and now a book trade newsletter. Some jobs I loved and some I hated. I've worked indoors and outdoors, for good bosses and... not-so-good. Like many people, work has defined me more often than I care to admit. Ever since I was a kid, I wanted to be considered a "good worker," no matter what the work entailed.

In 1988, Levine told the Paris Review: "I worked for Cadillac, in their transmission factory, and for Chevrolet. You could recite poems aloud in there. The noise was so stupendous. Some people singing, some people talking to themselves, a lot of communication going on with nothing, no one to hear."

Although I never worked in a car factory, I know what hard work and hard words are, and how well they mesh when the gears align. I also know how hard not having work is. Levine's words traveled these tough roads--the complicated pain/pleasure of aching bones and brain, the odd combination of power and powerlessness. Words often saved me, as did work. I think Levine felt that way, too.

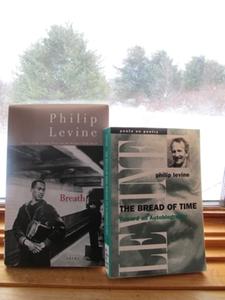

In The Bread of Time, he wrote: "My life in the working class was intolerable only when I considered the future and what would become of me if nothing were to come of my writing. In one sense I was never working-class, for I owned the means of production, since what I hoped to produce were poems and fictions. "

|

|

| Winter and Levine's work |

|

His friend Edward Hirsch told the L.A. Daily News that Levine captured the ways "ordinary people are extraordinary."

Part of the genius of Levine's poetry is his understanding of working class kids like me, who were born to be laborers, no matter what work we do. Can't outgrow or outrun that genetic code. I've seen photos of my ancestors, all those sorry-assed ghosts in the grainy old marble mill photos with their weary-eyed expressions and mute accusations--"What are you looking at us for? We've got work to do."

Fortunately, I found Levine and his good words a long time ago:

waiting at Ford Highland Park. For work.

You know what work is--if you're

old enough to read this you know what

work is, although you may not do it.

Forget you. This is about waiting,

shifting from one foot to another.

For a few years, I taught an English Comp. course at a community college. Many of the students had lousy jobs or were unemployed, just looking for a break, another chance, a fresh start, whether they were 23 or 43. Work was one of the things I asked them to write about. We read "What Work Is" together. They already knew what work was, but they worked their way through Levine's words with me. If a poem can be "gotten," some of them got it. And if they never read another poem, they really read this one.

So here is what I know. This week I'm mourning the death of Philip Levine, even as I celebrate his life the best way I know how--by reading him again. He'd done his work. On February 14, he punched out one last time on a cold winter's day.

From "Naming":

in the twilight and hiding the stalled cars

on Grand River. Head whitened with snow,

Eugene lets the receiver slip from his hand.

I can see his eyelashes weighted with ice,

his brown eyes slowly closing on the image

of who I was, who I will always be.

From "Zaydee":

a moment and then were still,

the long streets were still and the snow

swirled where I lay down to rest.

Good job, Phil. --Robert Gray, contributing editor (column archives available at Fresh Eyes Now)