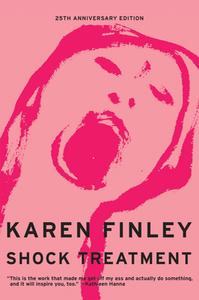

Karen Finley is a writer, artist and educator whose controversial work has placed her at the center of America's culture wars for over a quarter century. In 1990, her book Shock Treatment, a collection of poems, essays and drawings, ignited fans and critics with its unflinching depiction of the trauma related to homophobia, misogyny, the AIDS epidemic and cultural close-mindedness. That same year, she and three other artists were denied grants from the National Endowment for the Arts for "indecent" subject matter in their work--a case that went to the Supreme Court but was decided against the artists. In September 2015, City Lights Publishers released an expanded 25th anniversary edition of Shock Treatment with a new introduction from Finley, in which she reflects on creating the work.

Karen Finley is a writer, artist and educator whose controversial work has placed her at the center of America's culture wars for over a quarter century. In 1990, her book Shock Treatment, a collection of poems, essays and drawings, ignited fans and critics with its unflinching depiction of the trauma related to homophobia, misogyny, the AIDS epidemic and cultural close-mindedness. That same year, she and three other artists were denied grants from the National Endowment for the Arts for "indecent" subject matter in their work--a case that went to the Supreme Court but was decided against the artists. In September 2015, City Lights Publishers released an expanded 25th anniversary edition of Shock Treatment with a new introduction from Finley, in which she reflects on creating the work.

What inspired the 25th anniversary edition of Shock Treatment?

The book has remained in print for 25 years, but I realized it was coming to an anniversary and was invited to see about having a new edition. At first I thought "why?" but after reviewing the writings, I was startled at how relevant they are to now. So many of the issues that we're dealing with today, I speak about in the book--issues of the outsider, censorship, sexual abuse, rape, otherness, war, disenfranchisement, relationship with the family, the artist, gay rights.

I think that my process as an artist at that time--as a younger, emerging artist--was to situate myself within the artist as historical recorder. This collection is my participation in the discourse of the artist as historical recorder.

With events like what's happened in San Bernardino, Paris, Lebanon... how do young people relate to these extraordinary world events that are unfathomable? How do we respond? How do we make meaningful content? By looking at the writings I was doing, I'd like to inspire artists and emerging artists to take their pen or brush and record for the future, and the world around them, from the artist's lens. Writing and creating a document is a participation--to make an action, and to be a witness, and to respond.

How have responses to your work changed since its original publication?

[In the past] there were a range of responses; some of the texts in that book were censored by the government for being indecent. Mentions of pro-choice, gay rights, sexual violence were considered inappropriate.

But I still don't get a free ride with my writing. Just yesterday I was confronted by someone who thought, "Why are you expressing so much anger?" There's still misogyny in our culture with regards to a woman's place. Speaking out with passion is considered inappropriate; you can still see that 25 years later in the scrutiny of Hillary Clinton. That's something I'm very, very interested in--women not having to apologize for sticking out. I haven't figured that out yet. But I am thinking about trying to start some support groups for women or anyone speaking out about issues that are not part of a dominant culture. You have a right to be angry. We need to have a place in our society where we can be expressing discomfort and conflict and that's what I'm interested in now. What do you see as the most significant social changes in the past 25 years?

What do you see as the most significant social changes in the past 25 years?

There's been some progress in terms of gay rights, gay marriage, and that we do see more representation with women and minorities, but not so much that writing [from the 1990s] seems so historical.

Sexting, for instance, wasn't in existence at that time. But people get so bent out of shape about the body and sexuality it's crazy. It's like we could be in 1840, it's so Victorian to me. I feel that there are some aspects of 2015 that are more Victorian than 1990 about sexuality, and also freedom of speech issues. And even with violence. In [Shock Treatment], a lot of these issues are covered. Sometimes, poetic writing can have a human connection that goes beyond a certain era.

As someone who works in so many different mediums--performance art, installation, illustration and so forth--how is writing particularly challenging or rewarding?

The voicing. The speaking out of the writer. It's just pen to paper. There's an economy to it. I feel in some part, the writing can be more powerful than the image. Artwork inserts itself within the economy of the market, so very few own a particular object. But for the writer, it is owned by many. That intimacy you have is not collected or put into a museum. That's the power. We're all writing, we're all speaking all the time. You don't need a studio. The economy for it is just that you need that drive and desire to do it. The fact that these words can change. I want to be part of the revolution. Artwork is always part of a caste system within capitalism, but writing and speaking can exist within an economy that can be supported by not just the lucky. That's what I like about City Lights--it's a system created by a writer and the pocketbook poets. I like being part of that indie community.

Have changes in technology influenced your work?

In some ways technology has made it more difficult. I am a private person, and my art comes out of these moments of privacy, moments of invisibility and deep reflection. For me, as an introvert, my art and my inspiration comes in these spaces--the profoundness comes in deep engagement--and that often comes from another person. That's what's lost in technology. I can do some, but my work is located in an intimacy. I like having social media, but I don't want to forget the intimacy and the profoundness.

A lot of my work comes out of one-on-one conversations. I love human interaction face-to-face; it could be in a taxi or anywhere. A lot of art-making or communication is invisible. A one-on-one moment with someone that is not documented can be very powerful. You don't always need to have proof. At the same time, I think social media is fantastic. There just has to be a balance. Just because you have a car doesn't mean you have to stop walking. --Annie Atherton