|

|

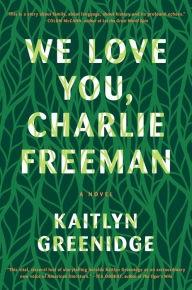

| photo: Syreeta McFadden | |

Kaitlyn Greenidge was born in Boston and received her MFA from Hunter College. Her work has appeared in the Believer, American Short Fiction, Guernica, Kweli Journal, the Feminist Wire, Afro Pop Magazine, Green Mountains Review and other places. She is the recipient of a 2016 NEA Fellowship in Literature, as well as fellowships from Lower Manhattan Community Council's Work-Space Program and the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference. She lives in Brooklyn, N.Y. We Love You, Charlie Freeman (Algonquin, March 8, 2016) is her first novel.

On your nightstand now:

Doris Lessing's The Golden Notebooks. I often think about how some authors become synonymous with a certain movement or a certain type of reader, and then they become lost. It's terrible, but I think it's just human nature. I knew Lessing as a favorite of second-wave feminists and so I was wary of reading this one. It's a revelation--it is everything that I think some people are struggling with now. How do white people of any sort of consciousness take into account their complicity in systems of racism, empire and white supremacy? How do progressives resist the urge to cannibalize our movements and our comrades? How can men and women ever be in romantic relationships together when we fundamentally misunderstand and miscommunicate? And the structure! She just goes for it. Like, "this novel is going to be structured in a weird and complicated way, with a conceit that seems a bit out of nowhere. But, whatever, you as a reader are in it now, so just take my word for it." I am trying to learn from that confidence.

Favorite book when you were a child:

I was a great re-reader as a child. I read A Tree Grows in Brooklyn nearly every summer from ages 11-18. Same with Jane Eyre. As a much younger child, probably Alice in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking Glass. I had two beautiful illustrated versions that I read again and again. At one point, I had the entirety of "The Walrus and the Carpenter" memorized.

Your top five authors:

Toni Morrison makes these grand pronouncements, almost like hypotheses. And yet, her work is deeply embedded in the techniques of fiction. I like how she can make a sweeping statement that works both as a way to define the fictional world on her page and as a critique of our culture. That sounds like a really basic skill, but it's so difficult to pull off. Mostly in novels, when writers try to do this, they limit it to talking about romantic love. Morrison is gimlet-eyed so can do this with any and every subject.

Gabriel García Márquez's novels can be read again and again and again, and a reader can find a different perspective each time. And he includes all of life--the sacred and the profane and the rude, too. I reread Love in the Time of Cholera a few months ago--the climactic scene of the two lovers, a meeting that is the culmination of decades' worth of unrequited love, is punctuated by an extended fart joke. I love that. And I aspire to write something similar one day.

Colette writes in the present, and has a catalogue of smells and tastes that are unparalleled in anything else I've read. She is one of the first writers I discovered who wrote about eating ink and paper--a habit of mine from childhood. For that, I will always feel an affinity with her.

Salman Rushdie's early novels relentlessly mine childhood and the drama of family while insisting that both are relevant to how we understand self, our communities and nationhood.

Evelyn Waugh has these moments in his novels where the whole tone of the book can change in a single sentence. It happens in Vile Bodies (my favorite) and A Handful of Dust--a book so bleak it actually pains me to reread it. I love that shift in tone--from the bubbly effervescence of a Nancy Mitford social satire to deadly earnest, deadly serious drama where all the excesses of the previous pages suddenly have very real consequences.

Book you've faked reading:

I have actually read Don DeLillo but I am not a DeLillo fanatic. Many of my writer friends are DeLillo lovers and I wish I could understand the appeal. I read his books and the words just wash over me and don't leave any impression. In my more insecure days, I faked the funk and pretended to fangirl alongside them. I understand he's enormously important for many but he leaves me--not cold, exactly. Probably just indifferent. Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Legs McNeil's The Other Hollywood and Please Kill Me. Absolutely beautiful pieces of journalism and proof of what oral histories can do when they are edited with a sense of humor and irony.

Book you hid from your parents:

Oh, probably the historical romances and fantasy novels I read as a teenager. I knew those books were déclassé. I liked fantasy novels that no one else did, so I didn't even have the solace of a community of fandom. My tastes ranged towards things like The Spellkey Trilogy by Ann Downer. I think I was the only person on earth who read those. The Oracle Glass by Judith Merkle Riley. And this book whose title I have blocked out because it was so embarrassing. It was a fantasy novel about half-cat, half-human creatures who could also fly and had enormous amounts of sex on top of pink cloud palaces. That was humiliating to read and enjoy as a 14-year-old who knew she should do better. Recently, I told a friend about that one. He is also a nerd, but even he said, "I would have beat you up if I saw you reading that back in the day."

Book that changed your life:

Rollerderby by Lisa Carver. I read it when I was 12 and my family had just moved into public housing, and I'd just started going to a very snobbish private school. I was acutely aware of class and acutely anxious about the class lines I straddled. Rollerderby was an unabashed celebration of lower-class and working-class life. Every woman that upper-middle class Bostonians claimed to be scandalized by in 1993--Danielle Steel and Dolly Parton and Tonya Harding and Peggy Bundy---was celebrated in that book as a trash goddess. It was breathtaking. So counter to everything I knew that when I first read that book, it straight-up terrified me. It probably has informed my worldview as much as any other piece of theory or history. It taught me the power in being underestimated, the power in being too feminine or too gauche or too loud or just too much. Too bad Lisa Carver later hooked up with a white supremacist. I was rooting for her.

Favorite line from a book:

"I warn her. I say this is not a man who will help you when he sees you break up. Only the best can do that. The best--and sometimes the worst." --Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys

And, also from Wide Sargasso Sea:

" 'I am not used to happiness,' she said. 'It makes me afraid.' "

Five books you'll never part with:

I have moved and been evicted more times than I can count at this point in my life. Every time we moved, my mother would complain about all the books, so many books, we had to pack. But we never got rid of any of them. These are the ones that I still have, after countless moves since I was a kid, and that come with me to every apartment: One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez; Imperial Leather by Anne McKinnon; Role Models by John Waters; Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë; and What's Happening to Me? by Peter Mayle. I keep this last one because it's one of the few picture books from my childhood that I still have. As a kid, I would pour over this book for hours, trying to figure out the mysteries of puberty. It was supposed to be an illuminating book, but it is full of confusing visual euphemisms. I spent a significant part of my eighth year trying to figure out what a wet dream was because this book represented it as a rain cloud hovering over a young boy's bed.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez.