|

|

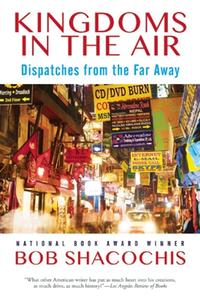

| photo: Mace Fleeger | |

Bob Shacochis's first collection of stories, Easy in the Islands, won the National Book Award for First Fiction, and his second collection, The Next New World, received the Prix de Rome. He is also the author of the novel Swimming in the Volcano, a finalist for the National Book Award, and The Immaculate Invasion, a work of literary reportage that was a finalist for the New Yorker Literary Award for Best Nonfiction Book of the Year. The Woman Who Lost Her Soul won the Dayton Literary Peace Prize and was a finalist for the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Shacochis is a contributing editor for Outside, and his op-eds on the U.S. military, Haiti and Florida politics have appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal. His collection of travel writing, Kingdoms in the Air, is published by Grove Press (June 7, 2016).

On your nightstand now:

A heap, starting with a trio of radioactive books essential for researching my new novel, based on events that took place during Argentina's Dirty War: the first, Nunca Más, is the report of the novelist's Ernesto Sábato's commission to investigate the 30,000 people, mostly students, disappeared during the so-called war. It is a self-described report from hell. The second, The Flight: Confessions of an Argentine Dirty Warrior by the journalist Horacio Verbitsky, is as powerful and provocative as any novel ever written. The third is Children of Cain by Tina Rosenberg, one of America's best and underappreciated journalists. A fourth book, an honorary member of this group, is John le Carré's The Little Drummer Girl, because I can't write my own novel without being inspired by le Carré's extraordinary prose and storytelling. At the bottom of the heap you'll find the manuscript for Perfume River, Robert Olen Butler's wintery new novel about Vietnam vets, and the galleys for Peacekeeping, Mischa Berlinski's second novel, which I recently reviewed for the Washington Post. Also, my wife just finished Anthony Doerr's All The Light We Cannot See and, after electrifying me by reading the last page out loud, she reached across the bed to hand me the book, which I had no other recourse but to park on the floor. I wish I had a bigger nightstand.

Favorite book when you were a child:

Although my mother never earned her high school diploma until I was in high school, she spent her girlhood as a voracious reader, and I spent my boyhood reading her hand-me-down copies of the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew series. But the first book that really slammed into me when I was a kid, during the Camelot days of the Kennedy administration, was T.H. White's The Once and Future King. The book shimmered with all the magic I felt in the presence of the Kennedys, who attended the same church as my family did when I was growing up.

Top five authors:

Let's stay with the living. Off the top of my head: Joan Didion, Hilary Mantel, Richard Powers, Adam Johnson, Jennifer Egan. Just ask, and I'll give you 50 more.

Book you've faked reading:

Well, who hasn't faked James Joyce? But my answer, with apologies to my former student Tom Bissell, is Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace. Wallace was, for his generation, the overactive voice of youth, which worked splendidly for his journalism, but I think I'd have to be a hell of a lot younger to appreciate his novels, except his very first one, The Broom of the System. Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Surely you mean books (plural), yes? And surely you'd publish the 100,000 words of my proselytizing? For many years, the book that was the focus of all my writerly religion was Gravity's Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon. During my 20s and 30s, I don't think I would even let you be my friend unless you kissed its cover. Then in my 40s I read it a fifth time and thought, oops, I don't think I better do that again. "Groovy" was not aging well.

Book you've bought for the cover:

I adore great cover art, and I'm thrilled, honestly, mostly, to see a visual artist's interpretation of my own work. That said, I don't ever remember buying a book just because of its cover.

Book you hid from your parents:

Mein Kampf? You didn't have to hide books in my house. You had to hide your cigarettes. Even my father was lazy about hiding his Playboy magazines.

Book that changed your life:

More precisely, it's not books that change your life, but reading itself, and into that template you can, over a lifetime, insert many, many books that keep growing and changing and refining your sensibilities. Or not. I know more than a few good readers who are bad actors. Anyway, to answer in the spirit of the question, the book that finally seduced me across the threshold, from reader to wannabe writer, was J.P. Donleavy's The Ginger Man, which electrified me with its delicious wickedness, but more than that, made me understand for the first time the beckoning playfulness of style, the shape-shifting possibilities of voice.

Favorite line from a book:

The last line of Russell Banks's Continental Drift: "Go, my book, and destroy the world as it is."

Certainly a last line that must somehow find its way into your heart as a writer, not a responsibility or a command but an article of Whitmanesque faith.

Five books you'll never part with:

The ones I lent out to friends that never came back to me. Where did my beloved copy of Thornton Wilder's The Bridge of San Luis Rey ever end up? It's still out there, wandering the world. I miss it so. Maybe one day it will meet up and have a beer with my first-edition copy of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Speaking of the Latin boom, The Kingdom of This World by the Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier, one of the founding fathers of magical realism. Carpentier is a writer who can teach you, as a writer, to run naked through the universe.