|

|

| photo: Maarten de Boer | |

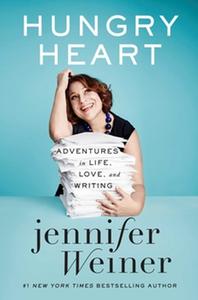

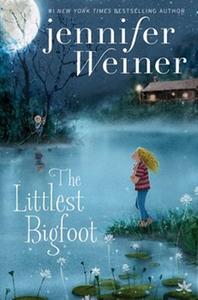

Jennifer Weiner is the #1 New York Times bestselling author of 14 novels and collections, including In Her Shoes, The Next Best Thing and Who Do You Love? Her newest are her first middle grade novel, The Littlest Bigfoot (Aladdin), and the essay collection Hungry Heart: Adventures in Life, Love, and Writing (Atria). Weiner is a graduate of Princeton University and a contributor to the New York Times opinion section. She lives with her family in Philadelphia.

Your writing career started in journalism, and you've written essays and articles while a full-time novelist; what made now the right time to publish a collection of essays?

I was 45 when I wrote this book, which felt like a natural halfway point, a good time to stop and take stock. The short answer is that my publisher asked for a collection. The initial plan was for the book to be about 50% pieces I'd published before, and 50% new material, but as I began writing, I started to tell all the stories that I tell in person, in response to readers' questions: How did you become a writer? What was it like having a book turned into a movie? How do you balance motherhood and work?

I wanted to answer those questions, for my readers and myself.

In "The F Word" essay, you confront your daughter when she calls another girl fat. What are your thoughts on how we should be talking to our young boys who embrace that mindset?

Here's the truth--I live in Girl World. I have two daughters. From September through June, I live with them, and my assistant, Meghan, and Terry, who helps with the house stuff and the childcare. During the summers, I'm in Cape Cod with my daughters, plus my mom and her partner (and my poor husband, who, I joke, will probably get his period some day if he does this long enough). I work in publishing, which is run, largely, by women. My agent is a woman, my editor is a woman, my publisher is a woman, and her boss, the head of Simon & Schuster, is a woman. My editor at the New York Times is a woman; my publicist is a woman; the producers and on-air talent of most of the TV shows I go on are women. Aside from the occasional bruising Twitter scrap, I can go weeks--months--in this utopian bubble, where women's voices are heard and respected, because women's voices are all there are.

And then, occasionally, I get jolted back to reality. Like, last summer, I was invited to be part of a "chemistry test" for a network talk show. The deal was, the executives (women!) had picked two guys they wanted, and were looking for women with whom these guys would have chemistry.

And then, occasionally, I get jolted back to reality. Like, last summer, I was invited to be part of a "chemistry test" for a network talk show. The deal was, the executives (women!) had picked two guys they wanted, and were looking for women with whom these guys would have chemistry.

Given my own woeful dating history--that, and the fact that the first member of the chosen pair I met seemed to find me actively repellent, could barely make eye contact, and didn't laugh at any of my jokes--I should have just gone home. But I didn't... and so I wound up in a room, on camera, with these two dudes, who were locked in a torrid and clearly exclusive bromance. One was a former professional athlete--the kind of guy who, I suspect, had spent decades on the road with groupies throwing themselves at him. The other was a country/western DJ, who was not a professional athlete, had not had women throw themselves at him, and couldn't have been more impressed with the jock. The two of them were talking over me (and the other women who were part of the test), ignoring us, laughing at us. At one point, the former athlete rolled his eyes and said, "Oh, you the privileged white girl they sent up in here." And then the two of them had a nice long chuckle, and went back to swapping stories about how poor they'd both been.

It was infuriating. It was invalidating. It was also an important reminder. There are still rooms like this; still businesses like this, still panels and conferences and television networks and Fortune 500 boards like these, where, if there's a woman, she's sometimes the only woman in the room, and if she says anything, she might be heard, or she might be ignored, or belittled, or laughed at, or sexually harassed or objectified, or she might have her experience invalidated, right to her face (I just read an essay where a woman recounted being on a panel her company put together to address its summer interns. When the female interns asked about her experiences, she said, "You can do well here, but you need a thick skin," and then the men on the panel said, "Oh, no, we all get along here," and "women are respected.") I can't imagine anything more invalidating than having men say they understand your own life and your own experiences better than you do... but I think that it happens a lot to the women who aren't lucky enough to live in Girl World.

So how do we talk to boys about it? I think we start by just talking. Just the act of speaking your truth, with the implication that your female voice and your female story matter, are both important. You make sure that what you're showing your boys is what you want them to grow up believing. If you want them to believe that there is beauty beyond a 25-year-old white, blonde, size zero, then you act like you believe it, too. If you want them to believe that women's stories matter, then you read books by women. If you don't want them to judge women based on their appearances, you can't do it, and you can't surround yourself with people who do.

So how do we talk to boys about it? I think we start by just talking. Just the act of speaking your truth, with the implication that your female voice and your female story matter, are both important. You make sure that what you're showing your boys is what you want them to grow up believing. If you want them to believe that there is beauty beyond a 25-year-old white, blonde, size zero, then you act like you believe it, too. If you want them to believe that women's stories matter, then you read books by women. If you don't want them to judge women based on their appearances, you can't do it, and you can't surround yourself with people who do.

You've stood up for your genre and in many ways are helping to change the playing field for future writers. What recommendations would you offer to minorities of any stripe who also want to speak out and make changes?

There's a quote by Elie Wiesel I love that says, "We must take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented."

If nobody speaks up, nothing gets better. If you study the history of social movements, you know that there always have to be those people who are willing to stand up and say, "this is wrong," and "this needs to change." Being the one who says it will not make you popular--especially if you're a woman. But if you want things to change, then you can't stay quiet.

I think, for me, being Jewish is part of this. Jews believe in tikkun olam, that all of us are required to do what we can to heal the broken world. Which means that silence in the face of injustice is not an option. Speaking up does, still, get you slapped down, and called names, and called ugly, and dismissed. But it's necessary. And I think, ultimately, it can't feel good when you know something is wrong and you're not saying anything about it. At least, it wouldn't feel good to me. --Jen Forbus, freelancer