It starts with the bread: a dark sourdough rye called Borodinsky. Then tins of fish. Cucumbers. Meat stewed until it falls off the bone, its original shape mere suggestion. Cold vodka or a fiery shot of Metaxa.

It starts with the bread: a dark sourdough rye called Borodinsky. Then tins of fish. Cucumbers. Meat stewed until it falls off the bone, its original shape mere suggestion. Cold vodka or a fiery shot of Metaxa.

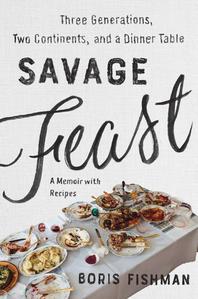

These are some of the many flavors of Boris Fishman's life, which he shares in his vibrant Savage Feast: Three Generations, Two Continents, and a Dinner Table (A Memoir with Recipes). "Some people don't leave home without umbrellas or condoms," Fishman writes, "mine, without food."

Fishman (Don't Let My Baby Do Rodeo, A Replacement Life) often tackles Jewish identity and displacement in his fiction. In Savage Feast, he addresses his family's emigration from Soviet Belarus in the long shadow of the Holocaust. The decision to leave is a heavy one, plagued by the risk of being denied permission and branded "refuseniks." But in 1988, when Fishman is nine, the family makes it to the United States.

In the new country, comfort comes from the familiar--flavors in particular. The family remains tightly knit, spoiling only-child Fishman with bountiful food, love and expectations even once he's an adult. Imagining a visit for dinner, Fishman writes, "When I get in, my mother will hang off my neck, my father will kiss my cheek, and my grandfather will slap me high five in a playful bit of Americana that--other than his ability to sign his name in English and the dozen words he's learned to bargain with the Chinese fishmonger--is the only English he knows after twenty years."

It's easy to feel at home in Fishman's writing; it's warm, reflective and frequently funny. His relationships with his grandfather Arkady, and Arkady's Ukranian home aide Oksana, are particularly compelling. In one instance, when Oksana gets the flu, roles reverse and Fishman's grandfather cooks for her. Seeing Arkady for the first time behind the stove was, Fishman quips, "like seeing the pope at the batting cages." It is from Oksana that many of the book's recipes come, and some of its memorable wisdom, too: "When you need people to leave, serve them dessert."

There's food for times of heartbreak (which Fishman is prone to, given his habit of falling for married women), like Cabbage Vereniki (dumplings) with Wild Mushroom Gravy. There is also food for times of joy, like the petite Syrniki: "pucks of lightly browned farmer cheese studded with raisins and spiked with vanilla... good cold or hot, at midnight or noon." Food anchors the memoir, but the recipes are the proverbial icing on the cake. The real meat of this story is its characters and the love that binds them--even when they bicker, say the wrong thing or go months without speaking.

Even more than a story of hunger, this is a story of love. Love of family and companionship. Love of romance and lore. Love of garlic, fish and the feeling of finally learning to identify and satisfy the simple but crucial loves for which everyone hungers. --Katie Weed, freelance writer and reviewer

Shelf Talker: This rich, memorable exploration of immigrant identity, culture clash and Soviet cuisine will linger long after the book has been closed or the last of the dishes within have been served.